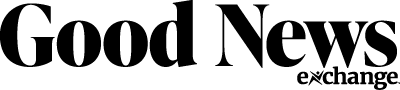

HIS LONG, narrow fingers danced across the strings, no longer obsessed with the movements of the bow in his hand. Instead, the world around him disappeared into the melody, the fiddle’s mellow yet vibrant tones coloring his early life in Ashland, Kentucky.

As a teenager, the instrument seemed more foe than friend.

“I started some on the fiddle about 16, but I’d get aggravated with the bow and wouldn’t pick it up for a month.”

It wasn’t until Ron’s New Year’s resolution at 17 that things clicked.

“My New Year’s resolution was to play an hour a day for a year. I knew the only way I was going to learn the fiddle was to do some woodshedding.”

Those initial practice sessions were a struggle.

“Within two months, I wouldn’t think about the bow. I was just thinking about my notes more.”

But slowly, Ron’s skills improved.

“And then I started advancing — and that hour a day turned into two hours, three hours, four hours. I’d get off the bus and run and get the fiddle. By 10 or 11 o’clock, Mom would be in the other end of the house, beating on the wall. ‘It’s time to put it up!’ But I couldn’t get it out of my hands.”

It’s no coincidence that a fiddle wound up in his hands.

“I have musical blood,” he said.

You might say connections to the “King of Bluegrass,” Jimmy Martin, and the “Father of Bluegrass,” Bill Monroe, bookend his musical destiny. His father, Carl Eldridge, filled in regularly with Martin and Monroe until his untimely death at 29. When Ron was 18, he met Kenny Baker, a 24-year member of Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys.

“When I met Kenny, man, I knew there was a better sound in a fiddle,” he said with deep admiration of Baker and his musical artistry. “I just walked up to him and said, ‘I want to learn what you’re doing.’”

And so began a mentorship and legacy that follows Ron’s life like Sharpie trails on a worn, folded roadmap along the Bluegrass Highway. A lattice of well-lived lines traces his travels in the ‘70s, playing in 18 different states with a list of bluegrass greats. Kenny’s influence is one of three other well-worn routes on their way to his Shelbyville home.

He said, “Rather than having one father, I feel like I had four: Roy, Kenny, Dr. Justice, and C. A. Bobo. And I had the best influence that you could ever ask. They all took me under their wing.”

Roy Kirk instilled in Ron a love of horses and a strong work ethic.

“I started riding when I was 4, and I’d do anything on [Roy’s] farm — fencing, cutting firewood, and just everything. Then, my first job after I met Kenny was for Dr. R. M. Justice, a past president of the Kentucky Dental Association. Six and a half years with him was like a college education.”

That college-like education led Ron to open his own dental lab at 24.

“I just appreciated the knowledge of the older people,” Ron explained. “I’d be sitting on their porches, talking to them about how things were done, and I really treasured their knowledge. I think it helped me more than anything.”

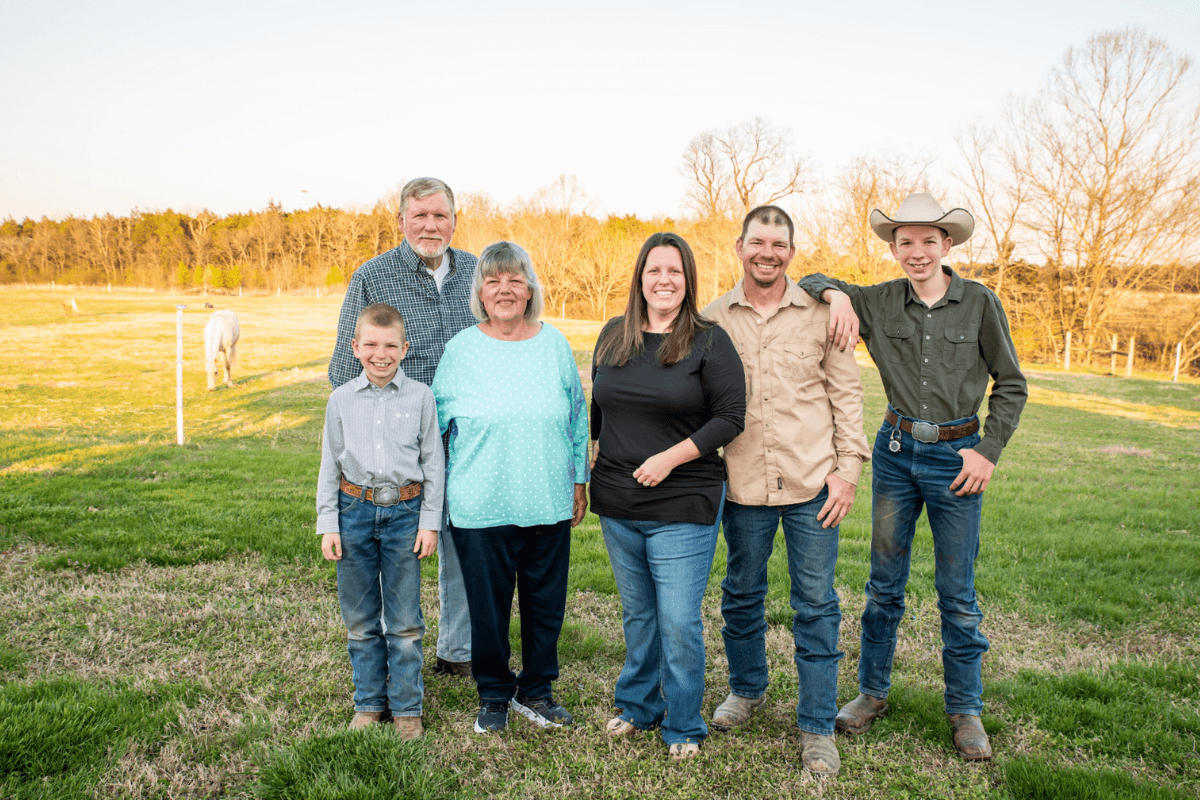

In 1986, music and horses moved him to Shelbyville. Two and a half years living in Nashville was two too many. With a Tennessee walking horse in training at C. A. Bobo’s barn, real estate agents were unsuccessful in locating a home for Ron in Bedford County. He decided to find a place by joining a Shelbyville band and making local connections through music. When he met Ernie Cook at Bobo’s barn, the line on his life’s roadmap permanently arrived in Shelbyville.

“I told Ernie, ‘If you ever need fiddle on something, give me a call,’ and he called me the next week.”

The first gig with Ernie was all it took to locate the perfect place. Bass player Mike Neeley knew of one for sale not far from him, and it was exactly what Ron wanted.

Although now retired, the home dental lab enabled him to immerse himself in the world of walking horses while keeping one foot firmly planted in the music that is the soundtrack of his life.

“I did raise five full brothers in a row that all got Celebration ribbons, and I’ve been a walking horse breeder since ‘85. I’ll have two Honor’s fillies go under saddle next spring,” he said with a smile.

Paying it forward is important to him. Three years ago, at a Kentucky bluegrass festival, someone introduced Ron to Wyatt Ellis, who, according to Bluegrass Today, is the youngest Gibson mandolin endorsing artist. Ron’s lifetime relationship with Kenny Baker opened a vault of history and connections to Wyatt, forming a new friendship. Today, Ron enjoys bridging the past and the future of bluegrass every chance he gets.

“I appreciate so much what people did for me. I get the most out of helping somebody young like that,” said Ron.

Wyatt said, “Ron’s one of my favorite people to be around. He loves bluegrass music and is excited about its future. I love to hear his stories about Kenny Baker, Jimmy Martin, and Bill Monroe.”

With Ron’s help, the past and the future of bluegrass connect today.

“He’s been a great mentor to me. He drove me to my Opry album release in Kenny Baker’s pickup and even let me wear [Kenny’s] Blue Grass Boy belt buckle. I’ve also gotten to spend a lot of time with Ron’s blonde fiddle and treasure every moment I get to play it,” Wyatt added.

For Ron, the desire to learn launched a lifetime of music that is a desire to influence the future today.

“Pass it on. There’s no bigger thrill for me than knowing I’ve made a connection that [helps] somebody out there playing with success. Like I heard someone say, ‘It’s better to try and fail than to succeed at nothing.’” GN