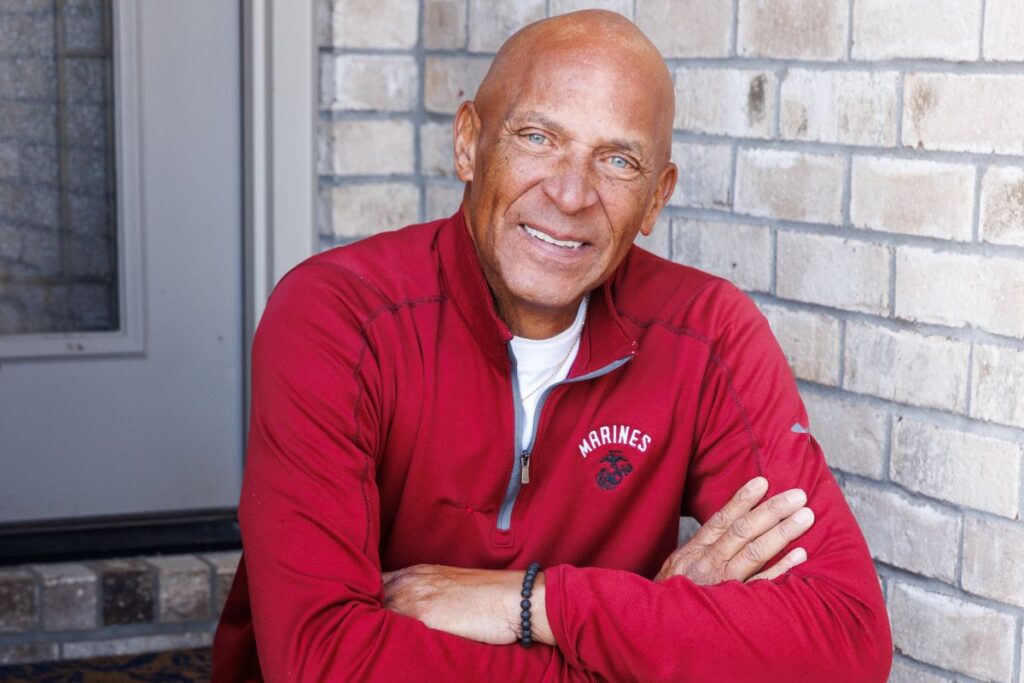

WHEN JAMES Lanier picks up the phone these days, he often does so after a nap. He explains it plainly, without apology, and with a smile you can hear through the line: he enjoys his daily rest.

It’s a small detail, but it captures something essential about Lanier. He is calm, steady, and grateful. And after decades of military service and law enforcement, he has certainly earned some peace.

A SURPRISE RIDE

Lanier grew up in Shelbyville, where he played tennis and football before graduating from Shelbyville Central High School in 1977. He went on to Martin Methodist College and Lincoln Memorial University on a tennis scholarship. Later in life, while serving in the military, Lanier continued to play and win tournaments on the tennis court.

After college, he returned home, unsure of what would come next. He told his parents he wasn’t finding any jobs.

His father gave him a solution to this problem, the young Lanier hadn’t seen coming.

“Get in the car in 20 minutes,” his dad said. On a silent drive, the two made their way to a military recruiting station. His father parked, turned to him, and said, “Don’t come back out until you’re signed up.”

Lanier was stunned. His mother’s philosophy had always been, “Give him time.” But, in this instance, his father had made up his mind. It was time for the son to make his own way in the world.

Lanier, who’d never considered a career bearing arms, walked inside. He signed the paperwork. Marine Corps boot camp would be held at Parris Island, South Carolina.

When asked what he was thinking during this process, Lanier’s answer was simple but meaningful. “I’mma make my daddy proud,” he said.

A LIFE IN UNIFORM

Lanier did more than that. What began as his father’s push turned into 28 years of military service.

He began his career in the infantry before becoming a marksman instructor, drill instructor, and communications specialist based in California, with a top-secret clearance. He served in every major conflict from 1980 to 2003, including Beirut, Grenada, the Panama Canal, Desert Storm, and the Iraq War. He talks about these orders with a straightforward calm.

“The unit I was in — deployed, deployed, deployed,” Lanier said.

He served three tours in Iraq. When the Marine Corps involuntarily separated him, along with many other soldiers, in an effort to downsize, he transferred to the Army reserves as a military police officer. After his third Iraq tour, he joined the Air Force, guarding C-130 aircraft in Nashville — sometimes after already working a full shift as a police officer.

“It didn’t matter where they put me,” he said. “I just wanted to do the toughest thing I could.”

Lanier used his military service as a bridge into civilian law enforcement. He started in 1990 with his hometown department, the Shelbyville Police Department, before moving to White House, where he advanced from patrol to corporal.

He later joined the Wilson County Sheriff’s Office, where he worked his way up to patrol lieutenant in the last decade of his service.

His message to the recruits he taught was practical: “You can’t do everything. You’ll wear yourself out.”

PASSING IT ON

Mentoring was always part of the work. Lanier led the Police Explorers program, from which seven of his students went on to pursue careers in law enforcement.

He also directed the citizens’ academy for 15 years, teaching a 13-week program on the realities of police work.

“We all get food on our plate we don’t like — you either eat it or you don’t,” he told his classes.

FAMILY FIRST

Lanier’s brother has also served, spending more than 20 years in the Metro Nashville Police Department’s traffic division.

“I’m proud of him,” Lanier said with a notable warmth.

Family, he added, is what always brought him back home. His sister continued to live in Shelbyville, and his mother passed away in 2022. When he came back to Shelbyville for her funeral, he reconnected with Phyllis, a woman he hadn’t seen for decades but had known since childhood. Their one date in the ‘80s had seemed like a good start, until James was sent to Hawaii on military business.

“We had a six-hour conversation,” Lanier said. Two years later, they married.

LOOKING BACK

Lanier keeps his military and law enforcement awards hanging on the wall, though he still finds it hard to take credit for all those shining accomplishments.

“I still can’t believe I did all that,” he said.

For Lanier, it all goes back to that summer day in Shelbyville when his father gave him 20 minutes to change his life.

“I thank my dad each and every day,” he said. GN