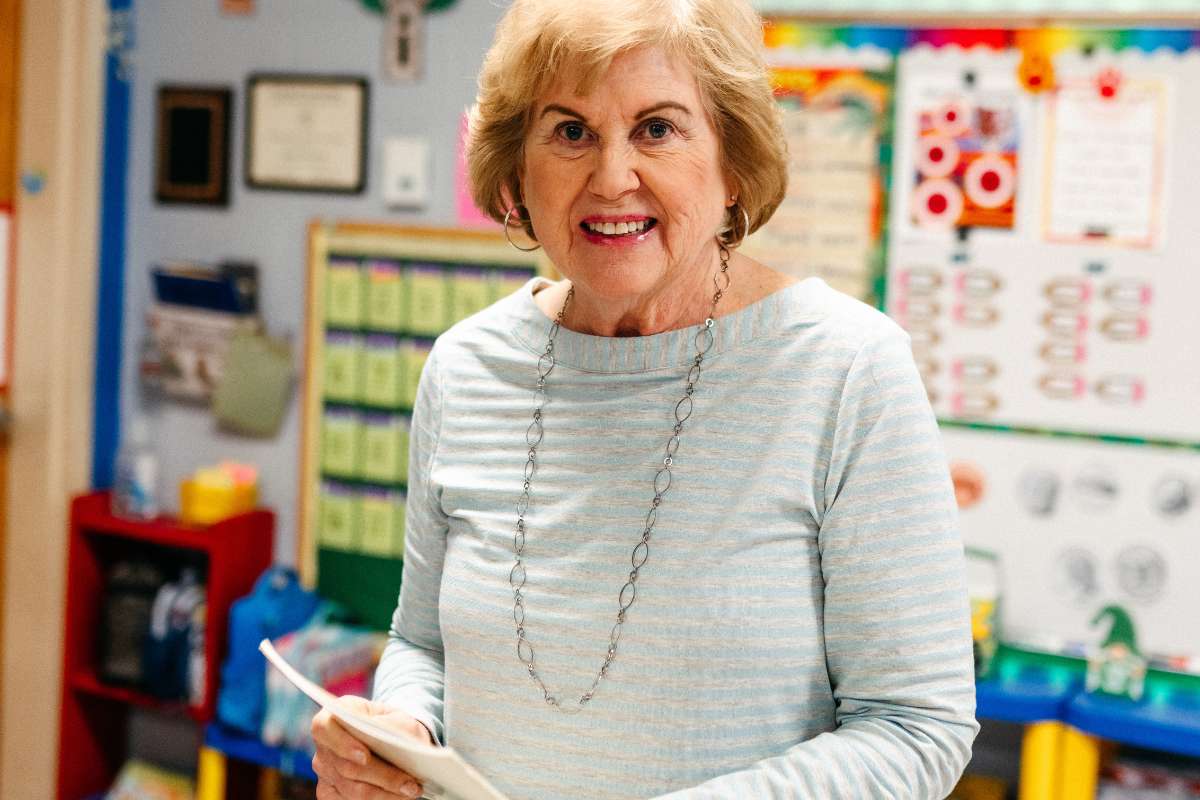

CHERRYE ROBERTSON is the principal of Byars Dowdy Elementary School in Lebanon, a school that ranges from pre-K to fifth grade. Her background in education is extensive and varied. Her career began as a teacher of first and third grade, and she quickly fell in love with her vocation. While teaching first grade, Robertson’s then principal approached her and asked if she wanted to become a literary leader.

Childhood literacy was the main plank that drew her to teaching.

“Teaching kids how to read was my thing. That was my passion.”

She readily agreed and was a literacy leader for three years. That was followed by another principal who approached her and, praising her skills, suggested she might consider the administrative track. That was something she had to carefully consider, as administration was not something she’d thought of as a career option. She decided, Robertson recalls, “to give it a shot.”

Child literacy and the need for children to truly learn are prime motivators in her work as principal. One thing that distinguishes Robertson from other principals is that she does the work along with the teachers. It’s not about telling teachers, “This is your data. What are we going to do about this data?” For Cherrye Robertson, it’s all about taking the team approach. If the team sees some hot spots, they need to act as a team to ensure kids are learning. Those issues continue to fuel Robertson’s passion for making sure all kids are learning, constantly driving her forward.

There are many hot spots for a principal, and they are constantly shifting.

“At the beginning of the year,” Robertson said, “everywhere is a hot spot — making sure everybody has what they need.”

And kindergarten, that vital introduction to the scholastic world, is always a hot spot. The school must ensure they’re giving kindergartners the foundational pieces they need. If the school provides all its resources and ensures kids understand, comprehend, and learn in kindergarten, some of the issues moving forward will be eliminated.”

Roberston makes the interesting analogy that teachers are akin to doctors. Teachers, like doctors, have to give an assessment to see where the problem is. If there is internal bleeding, it must be ascertained where it is coming from. Once that is determined, the school can get in there and apply the exact procedure to fix it. Nobody wants their doctor to just look at the outside of them and say, “Oh, this patient looks great!” You want your doctor to care and see exactly where that problem is coming from.

And you want your doctor to follow up. At the end of the year, Robertson and her team go back to all of the grade levels and make sure they know that every child has truly made progress. And if that isn’t the case, what is the best approach?

“And that’s my job. It’s that cycle of assessing, diagnosing, and giving the intervention. Did it work? If not, now what?”

These are turbulent times for public schools, but the job has been relatively simple to Robertson. COVID notwithstanding, she feels the mission remains the same: ensuring kids are learning and making progress.

“That’s really the bare bones of what I do. It’s not harder; we just have to be more intentional with our time, which is what I tell my staff.”

Being a principal is an exercise in never-ending complexity. “I’ve just been doing it for so long, and so I actually get a little antsy if I don’t have several things on my plate to juggle in one day. Then it’s like, ‘Okay, I must be missing something!’”

It’s all a matter of prioritizing. The foundation of everything she does is supporting her staff and, quite simply, nurturing and guiding the students.

“If I accomplish both of those things in one day, or I’m doing work related to those things, that’s why I’m here. It’s just a balancing act.”

It is a balancing act that Cherrye Robertson undertakes with skill and enthusiasm. Teaching children to “unlock their potential” is a term that gets discussed quite often. But in reality, there’s nothing as important. GN