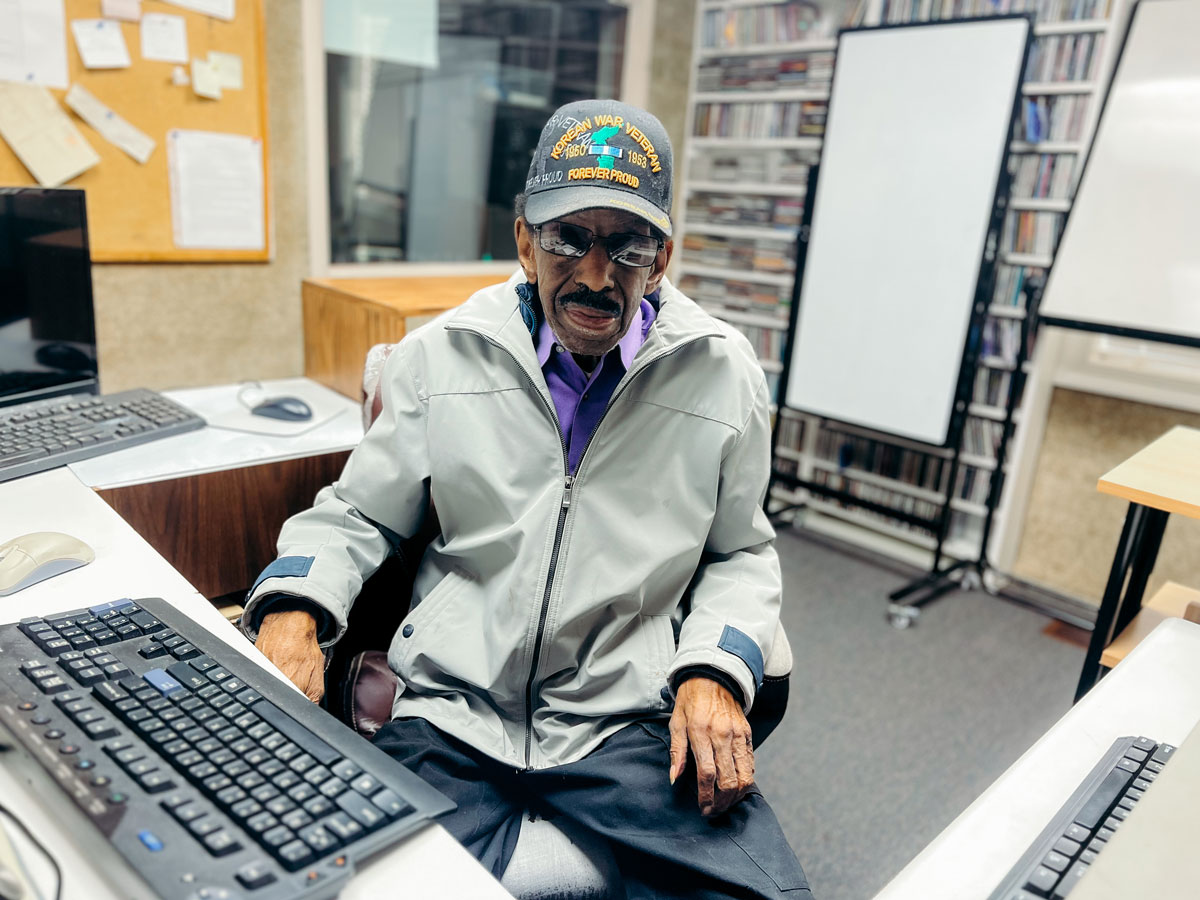

JOHN GRANT was one of the founders of Compassionate Hands, a homeless ministry that began in 2013. While no longer executive director, he is still a vital force behind this outreach.

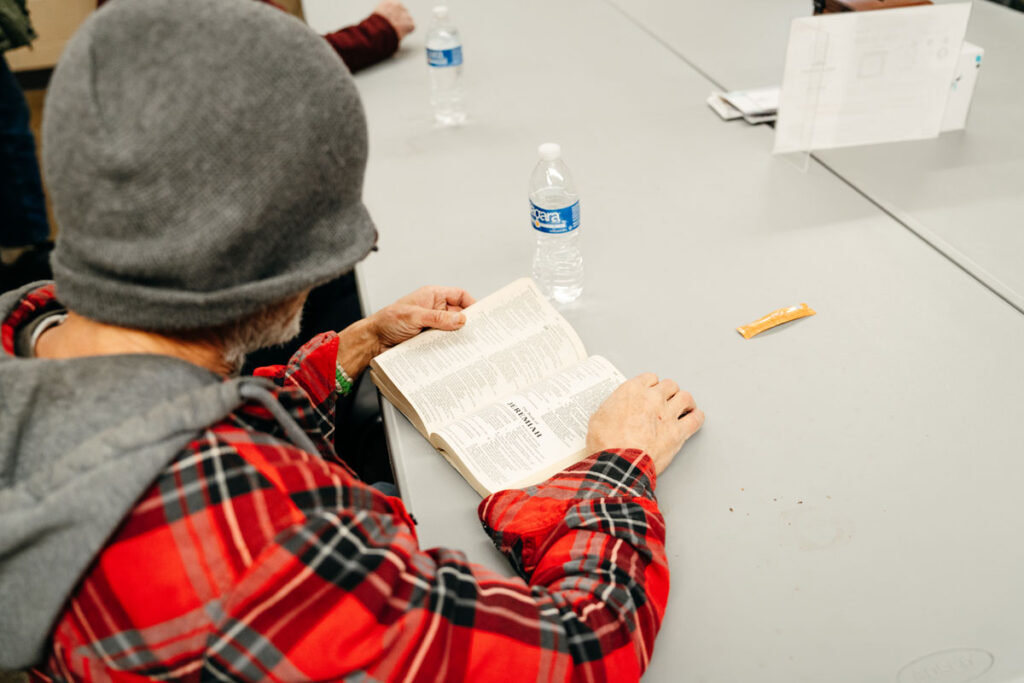

Since the beginning, the mandate of Compassionate Hands has been that “nobody freezes to death in Wilson County.” That means providing day shelter during the summer months — serving lunch, enabling people to wash their clothes. In wintertime, the need is for overnight shelter.

“Over the course of the recent winters,” Grant related, “we’ve served about 250 individuals who have spent at least one night with us. The men stay in our ministry center, and the women stay at a church.”

The problems of rural poverty are just starting to come to public attention. Much of the thrust of Compassionate Hands is assistance with those facing suburban poverty — a new, alarming development. Suburban poverty, Grant explained, “has been even less studied and recognized” than rural poverty. There are studies that show that the rate of poverty is higher in the suburbs than in the major cities.

Suburban poverty has its unique challenges and hardships.

“Suburbs are built for commuting,”

Grant explained.

The assumption is that everyone in suburbia has access to a car, which is simply not true. Wilson County, Grant pointed out, lacks a Social Security office — you have to drive a significant distance to the nearest office in Gallatin. The other assumption is that social services are not needed for suburban residents. And, of course, there is a strong stigma or outright disbelief that poverty does not exist in the suburbs.

There are three ways, Grant explained, how people become homeless. One, sadly, is addiction to alcohol and harder substances. The second one is untreated mental illness. The third is plain bad luck — the loss of a job or an expensive medical issue. When one lives paycheck-to-paycheck, even one of those factors can lead to a catastrophic outcome where a person or family ends up living in their car. And these are common suburban issues.

This last category — bad luck — is easier than others for Compassionate Hands to help. It’s a more stable sector of the population, with some means of support, and not usually afflicted by addiction or mental instability.

“We want to get them into housing.”

Other clients are given aid to travel out of state and back to their homes, where a family or job awaits. And others are placed in rehab programs. About 10% of Compassionate Hands’ guests need access to living arrangements for older adults.

“If we can get them Medicare, they can usually get into that program.”

Grant and Compassionate Hands are waging an uphill battle.

“The obstacles are so high, and the individual resources are so low.”

People have suffered a mental health crisis, have lost their housing, have been ousted from their families — the cases are wrenching.

“It’s hard work,” he conceded, “with very few wins.”

About half of the shelter guests grew up in Wilson County. Compassionate Hands, among other things, is an effort to aid friends, neighbors, and ex-schoolmates. This keeps Grant and his staff going, all of it undergirded by a strong faith that combats falling into despair or succumbing to a sense of futility.

Suburban poverty — and so much of poverty in general — is hidden or shaded from view. Grant and Compassionate Hands have taken on an enormous task, but a task that’s badly needed.

“One reason Compassionate Hands has succeeded,” he concluded, “is that our shelter has a really sweet spirit, even though the work is really hard. The guests will say, ‘You guys really care.’”

And that, in essence, is what it’s all about. GN