“GIVE ME liberty or give me death.” Those words — that famous utterance of Patrick Henry in 1775 — are an enshrined part of the history of the American Revolution. If pressed, most people probably know the source of this rallying cry was Patrick Henry. And then their knowledge, most likely, ends there.

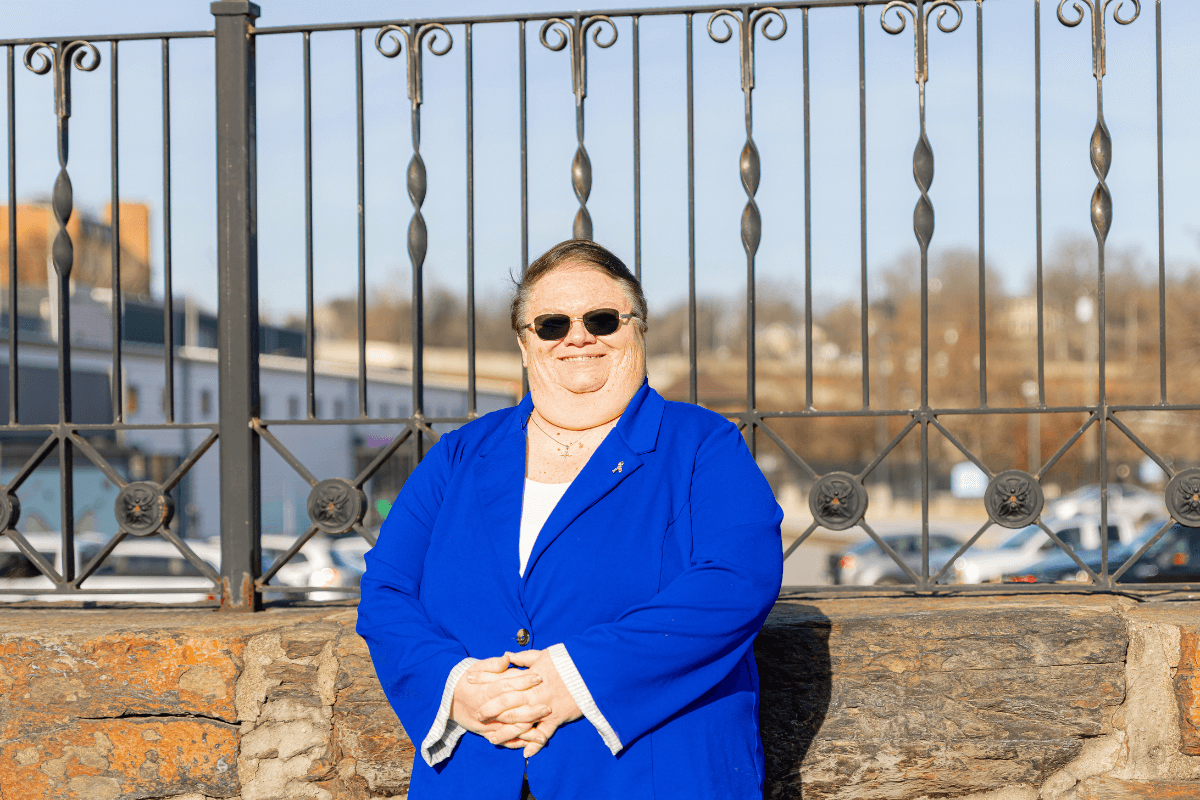

Cody Youngblood is determined to fill those gaps in knowledge. He is the director of historic preservation and collections at Patrick Henry’s Red Hill, the sprawling Henry family estate that is now a national memorial.

Youngblood has a master’s in historic building conservation from the University of York in the United Kingdom. In his position at Patrick Henry’s Red Hill, he does a little bit of everything, overseeing the historic buildings and structures and dealing with the museum’s 3D artifacts, papers, and documents. Red Hill has a new archaeology staff and saw the site’s first big dig last year. The intent was to identify what had been an icehouse and servants’ quarter, as well as Henry’s kitchen (whereabouts still unknown).

Henry’s legacy had been distorted by the biographers of the 19th century, who were far more interested in hero worship than historical accuracy, rendering Henry — and so many of the Founders — as demigods. The actual historical record is far more fascinating. Henry, aside from being one of the Founding Fathers, was a celebrated lawyer who engaged in significant cases like the “Parson’s Cause,” which was of enormous importance in the 1760s. He was governor of Virginia — and in that capacity, interestingly, signed Hampden-Sydney College’s founding charter. In the course of two marriages, he fathered 17 children.

Henry was also genuinely humble and, for a person of his repute, lived in surprisingly modest dwellings.

“He was someone who wasn’t concerned with his legacy,” said Youngblood — a striking contrast to Thomas Jefferson, who saved his papers because he knew he was an important historical figure. “Henry was concerned with the rights of individual Americans at this time, and he understood that’s what he was put here for. He wasn’t concerned with making sure his papers were saved.”

Patrick Henry’s Red Hill is also making a strong attempt to avoid the longtime omission of slavery from historical records. The memorial’s original name was the Red Hill Shrine to Patrick Henry, but as Youngblood pointed out, 147 enslaved and free Black people are buried on the site, in addition to members of the Henry family.

“Since the 1770s, when the property was first settled by white people, there have been African Americans here, so their history — very recently — has been intertwined with the story.”

Red Hill’s collection includes items from the enslaved people and the free Black sharecroppers who also lived here. Youngblood and the staff are expending a concerted effort to make sure this slice of history, including the horror of slavery, is remembered.

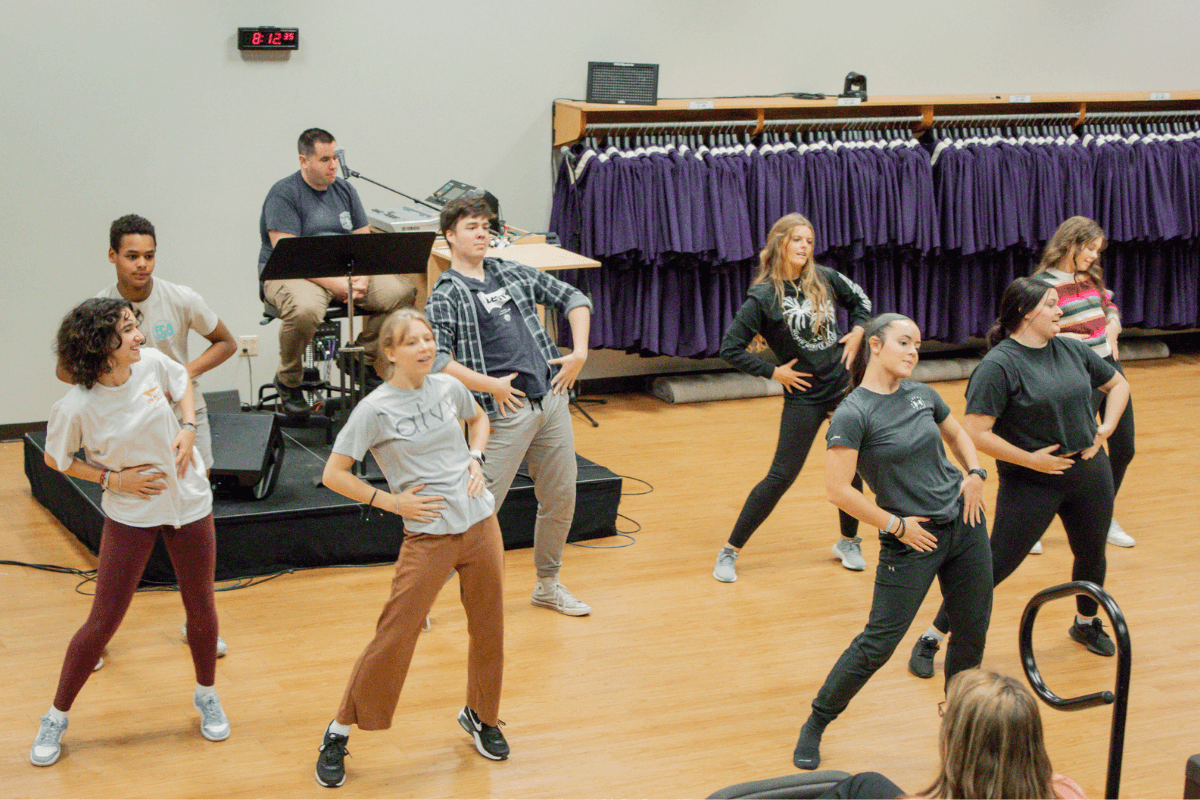

“Some of our best visitors are schools,” Youngblood explained.

Every year, the site hosts hundreds of elementary and middle school students. There is a large living history component, including volunteers wearing colonial garb and explaining topics ranging from colonial cooking and medicine to a look at blacksmithing and pottery. There are also summer camps, college students who come for guided tours, and a contingent of volunteers.

“The educational outreach is the thing I think we do best.”

There is an extensive archive available to both researchers and students. Red Hill has also partnered with the University of Virginia to present “Patrick Henry: Forgotten Founder,” an accessible online class. Non-students can get started at the university’s visitor center and enjoy an introductory video that welcomes them and discusses Patrick Henry. There is also a museum shop. Visitors can experience the reconstructed Patrick Henry house, his law office, the Henry family cemetery, and other outbuildings.

Visitors can experience Red Hill’s incredible natural surroundings, boasting striking views down to the Staunton River. Closer to the visitor center, there is a walking trail — the Quarter Place Trail. Historically, the Quarter Place was where the enslaved people and the free Black people lived — a half-mile trail that descends to some foundations of slave quarters and an extant tobacco barn. At the end of that trail is the Quarter Place Cemetery, where the enslaved people and free Black people are buried.

The study of history is full of misconceptions — that it’s a “dull recitation of facts and dates.” But history really is a living, breathing thing. And there’s no better example than that of Patrick Henry’s Red Hill. GN