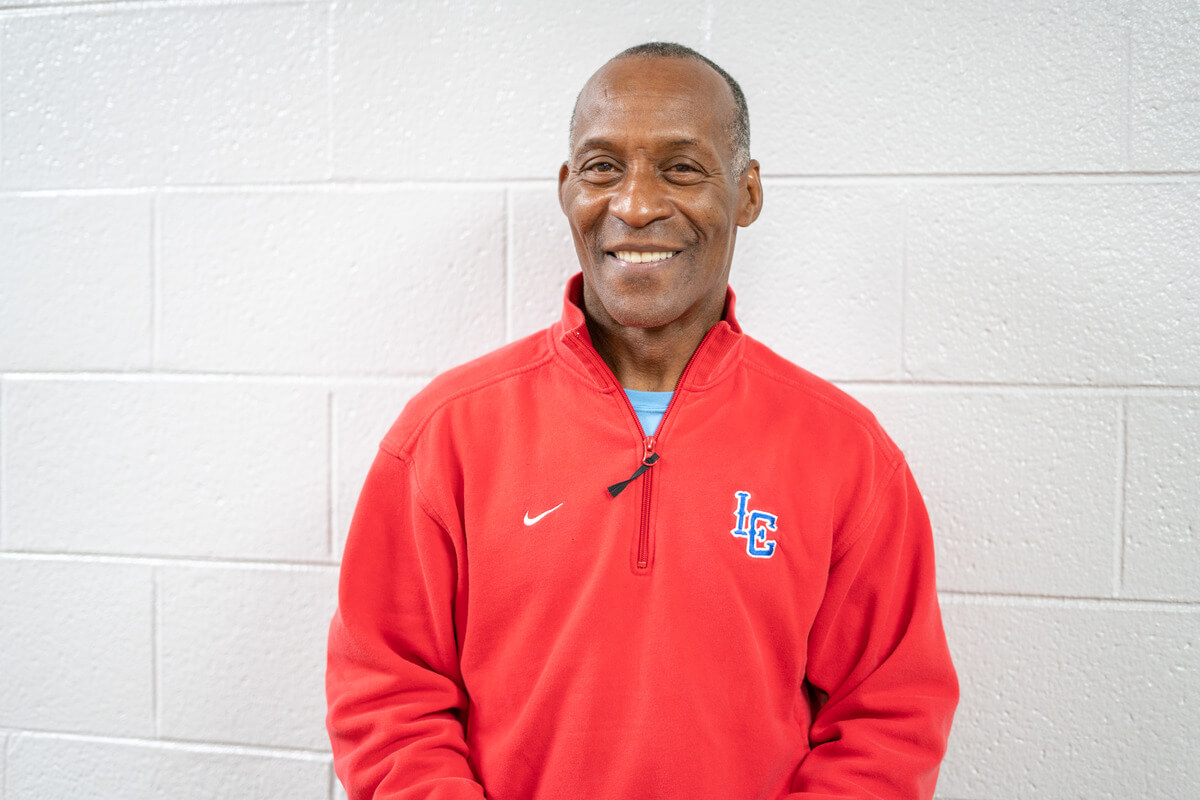

IN A SMALL rural community, where the pace of life is undoubtedly slower, one would think that a first responder’s job would be fairly cushy. Images like firefighters tucked in bed at the fire station, their home away from home, might come to mind. Some have joked that police officers write speeding tickets “because they have nothing else better to do.” Yet

all of these assumptions couldn’t be further from the truth. First responders in rural communities, especially emergency medical service (EMS) professionals in Fayetteville, Tennessee, are some of the busiest and most demanded experts in the workforce.

To put things into perspective, critical care paramedic Jacob Painter shared, “We average close to 400 to 500 calls a month. That’s about 23 to 24 calls a shift, so we stay incredibly busy for a small service.”

Painter has been a critical care paramedic for the past six years and an EMS service provider for 11 years altogether. He started working here locally as an EMT in 2010. Then, in 2020, he left to work at Vanderbilt in Nashville. Painter shared, “I worked in the [emergency room] at Vanderbilt, as a critical care medic, for some time. Then, I left there in 2021, to fly with Erlanger Life Force with their helicopter service. After a couple of months, I learned of the shortage of EMS in our town and decided it was time to stay and work at home, here in Lincoln County.”

Painter shared, “Even now, on a good day, we only have three ambulances staffed. When you only have three trucks, it’s kind of a heavy workload. But we are working on trying to get some more people so we can have more trained professionals in the field.”

Unknown to many, Painter and his co-workers answer more than emergent calls. He shared, “We do more than 911 calls. We do convalescent and scheduled calls, such as discharges from the hospital. There’s not a lot of downtime for us. Either we’re on the road doing a 911 call, a dialysis call, or we’re doing a discharge.”

Painter continued, “About 60% of the calls the service gets in a day are emergent calls,” making the vast majority of calls emergent in nature. When asked what is on his mind while heading to a 911 call, Painter said, “When I’m going on a call, I always anticipate the absolute worst-case scenario. I prepare myself mentally and physically. Then once I get there, if it’s not as bad as I made it out to be in my mind, I can downgrade. I am calm, because I have already prepared for it.”

Very few times has Painter’s preparation strategy not been successful. One of those times happened when he was still working as an EMT and got a call to work a murder-suicide scene. Unfortunately, there was no care to be provided. The job entailed cleaning up the scene instead. Painter shared, “There were three bodies on the floor, and it was very gory. It was really, really bad.”

Thankfully, calls of that nature are not the norm. Most calls elicit medical attention and end when the patient receives excellent and lifesaving care, making a positive story of someone returning to their loved ones. In fact, Painter shared that, in July, seven calls were from people who went into cardiac arrest. He said, “In the month of July, we had seven people who went into cardiac arrest. We also had seven people that got a pulse back, in the month of July. So we were seven for seven on ROSC [return of spontaneous circulation].”

Since Painter started this career path fresh out of high school, he has had a lot of time for his experiences to marinate in his own heart and mind. Being on the front lines in the medical field has caused him to change his outlook on life. He shared, “You know, seeing things that I’ve seen, unfortunately, can make you grow up super fast. I started this job right out of high school. Coming into this stuff as a young 19-year-old definitely changes your mindset. When you start seeing the things that we unfortunately see, your eyes are opened to how precious life is. Life has always been precious to me, but now it is super precious.” GN