Tim Leeper’s son, Kylan, was a funny, mischievous child who led a typical kid’s life — school, church, Little League. When he started exhibiting behavioral issues, his parents obtained counseling for their son. But diligent parenting is not a cure-all. In a moment of horrible judgment, Kylan committed a crime (arson) and was incarcerated at Trousdale Turner Correctional Center, a private prison run by CoreCivic. Five months later, he was dead, the victim of an accidental overdose — a pill secretly laced with fentanyl. His case is hardly an isolated one. Fentanyl deaths in prison are rising at an alarming rate. In Tennessee, drug-related deaths in prisons surged from six in 2019 to 49 in 2021, with nearly all (45) attributed to fentanyl, according to WPLN News.

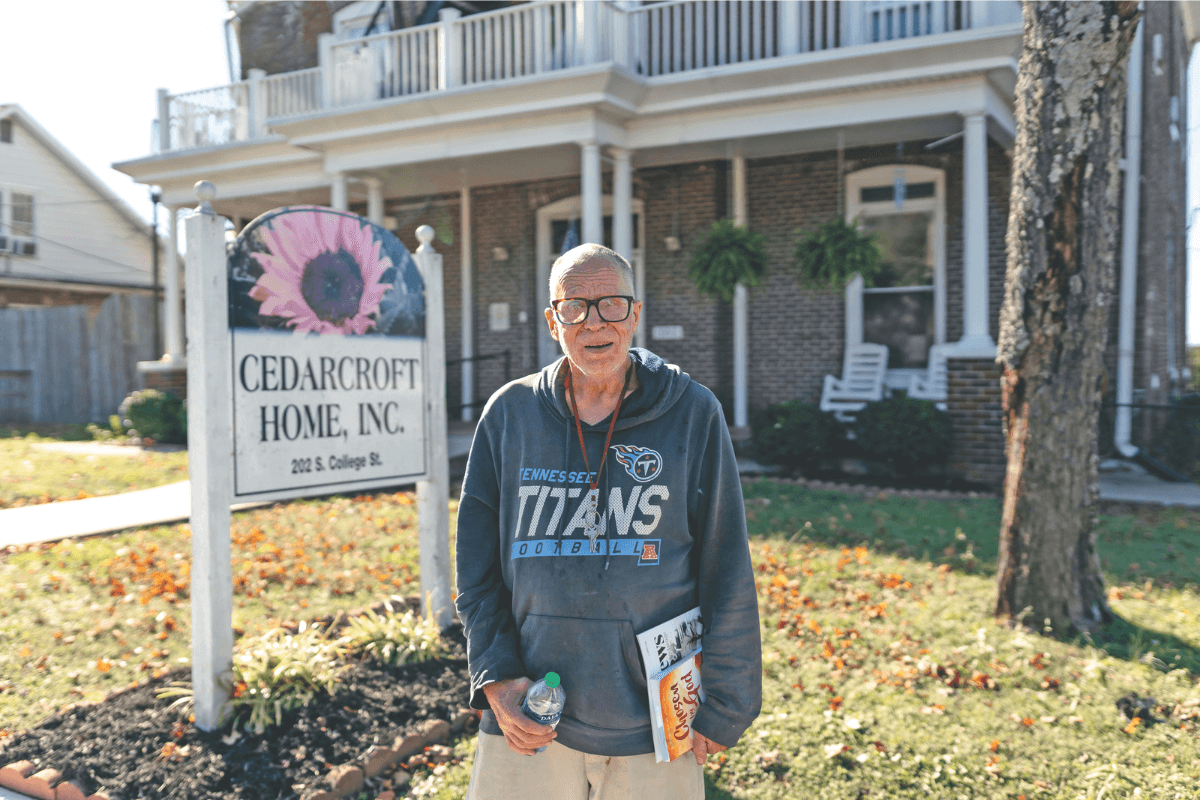

Kylan’s father, Tim Leeper, has turned this tragedy into a passionate advocacy for prison reform. Prisons, Leeper contended, are a necessary part of society. Nor is he excusing Kylan’s transgressions.

“There is,” he stated, “a better way to do what we’re doing, which is to take inmates and cage them. We don’t give them real rehabilitative opportunities. There are no tenets of dignity at all — the way that you’re talked to, the way that you’re treated.”

Prison is supposed to rehabilitate. Some inmates throughout America’s prisons have claimed that they feel caged and brutalized, but prison is supposed to rehabilitate people back into society. The situation can be all the more dire in private prisons, which in Tennessee can be chronically understaffed and have minimal oversight. Tim felt that Kylan was “basically put into a lion’s den.” Access to mental health and substance abuse resources may be limited for inmates. There are gangs. In essence, Tim believed we are taking “people who are in the worst shape of their lives. And it’s the worst time of their life, and you put them in a big mixing pot. It’s like a school for gladiators.”

Kylan did his best to keep in shape during his incarceration, working out diligently. Tim sent him money so he could purchase healthier fare from the commissary rather than rely on prison food. Kylan also kept in constant contact with his mother and father — behaviors not typically associated with excessive substance use. Kylan was not in active addiction, but as Tim Leeper pointed out, one does not have to misuse substances to die of an overdose.

“You take one pill that you think is a Xanax and has something else in it, and then you’re gone.”

Tim is creating Kylan’s Light, an advocacy outreach for prison reform. He and others have raised serious public allegations about CoreCivic. If one’s child, spouse, or family member is sent to prison, they rightfully have a reasonable expectation of guaranteed safety and security, which is not always the case.

One main thrust of Kylan’s Light will be to change the public perception of what an inmate looks like. An inmate could be a neighbor, a friend’s son, a cousin — someone who made a horrible mistake and finds themselves in prison. And often, as in the case of Kylan Leeper, incarceration becomes a de facto death sentence.

Tim Leeper makes the case for revamping the intake process. He believes prisons need behavioral and clinical staff who can ascertain the various reasons that led to a person’s incarceration. That is the time and place to examine these destructive patterns, “So you can be a different version of yourself when you get out. If you want to be a better father, or if you want to be a better family member, or a better friend to people around you, and you’re tired of this behavioral pattern that you’ve engaged in and you want to change it — this is where you do that.”

That’s the true nature of rehabilitation. And, looking at the scope of prison policy and the rise of private prisons, “We’re in a bad position right now.”

Tim Leeper’s account is both matter-of-fact and impassioned. On the day of Kylan’s funeral, he put his hands on his son’s casket and said, “I’ll do everything I can within my power” to advocate for prison reform.

When Kylan died, Tim got the strong feeling that his son was speaking to him: “Dad, I am OK right now. However, there are a lot of people in prison who are not OK. They don’t have anybody to talk for them.”

There are lots of “Kylans” out there who could — with help and assistance — turn their lives around. It is Kylan’s insistent voice that has motivated Tim to keep on advocating.

“I just want,” he concluded, “to make people aware.”