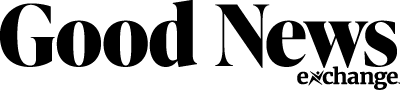

GRIEF IS a deeply personal and often misunderstood experience. Jack (Robert) Kennington’s career in grief recovery began as a profession and evolved into his calling. It’s a way to help others navigate the complex and often overwhelming emotions that come with loss. In 2015, Kennington became a certified grief recovery specialist, empowering him to teach, guide, and support others through their grief. This certification, however, is just one part of his broader mission to serve his community through Compassus, a hospice care provider in Tullahoma that serves six surrounding counties.

Kennington uses the Grief Recovery Method, hosting recovery groups and offering community members a space to explore their grief, share their stories, and find a path toward healing.

John W. James and Russell Friedman, who have since died, developed this program. It is based on a book they authored, which Kennington uses as a foundational text in his grief groups.

Kennington kicks off the sharing session with his story to build the group’s trust.

“One of the philosophies I have as a grief recovery specialist is that the leader always goes first,” he said.

Kennington is currently guiding a group through this process, which is now in its fifth week of the nine-week program. Participants engage with the material through weekly homework assignments and group discussions.

He primarily works with families who have lost someone under hospice care, but not exclusively. His grief recovery groups are open to anyone in the community, regardless of whether their loss was connected to hospice care. His sessions are free to the public. He also hosts lunch-and-learn sessions and other events for businesses and organizations seeking guidance for their team navigating grief.

His days are filled with phone calls and one-on-one meetings, providing comfort and guidance to those who are navigating the pain of losing a loved one.

Kennington also pursued Clinical Pastoral Education (CPE) at Erlanger Hospital in Chattanooga before he received grief recovery training. During his CPE training, Kennington was thrust into intense situations, including working with families who had just lost a loved one in a Level 1 trauma unit. These experiences equipped him with the skills to support grieving families, laying the groundwork for his future in grief recovery.

The Grief Recovery Institute has identified over 40 types of loss that can lead to grief, including divorce, pet loss, and even moving. Kennington found his personal experiences, including the loss of his grandfather in hospice care, a divorce, and the death of his grandmother in 2014, difficult to navigate.

This culmination of events drove him to seek out grief recovery training. Through this training, Kennington found the tools to address his own grief and gained the knowledge to help others more effectively.

Before his career in grief recovery, he worked at Chick-fil-A, known for its Christian values, for 20 years and later served in church ministry for 5 ½ years. He also earned his degree in business. These jobs laid the foundation for his work in hospice care, which began over a decade ago. Kennington has always seen his work as a form of ministry, a way to fulfill his God-given purpose.

“I felt God using me in each of those three positions and feel blessed to do what I do today,” he said.

The popular belief that “time heals all wounds” is widely accepted, but Kennington begs to differ.

“The only thing that’s going to help is to take action within time,” he explained. “If you just let time pass, grief does nothing. It’s probably just going to get worse.”

Through the Grief Recovery Institute, Kennington learned how to help others process their grief in a healthy way, avoiding the common pitfalls of unresolved grief, which can manifest in various aspects of life.

Many people are aware of the “five stages of grief,” popularized by Elisabeth Kubler-Ross. Kennington came to realize that these beliefs were myths. While Kubler-Ross’s work was groundbreaking, she later explained that the stages she described were meant for those who were dying, not for those left behind. This misunderstanding has led many people to expect a more linear process in their grief journey, which can result in frustration and feelings of inadequacy when their experience does not match the “stages.”

Kennington’s job in the community is to dispel these misconceptions and provide a space where individuals can explore their grief without judgment. His groups focus on the idea that grief is unique to each person, and there is no right or wrong way to experience it. By guiding participants through the Grief Recovery Method, Kennington helps them find their own path to healing, offering the support and tools they need to navigate the complex emotions of loss. GN