ALTHOUGH SHE has never lived in Tennessee, Dr. Elizabeth Taylor of McDonough, Georgia, has become the foremost expert on Camp Forrest, a piece of Tullahoma’s lesser-known history.

Named after Nathan Bedford Forrest, the camp was located on the land now owned by Arnold Air Force Base. It housed prisoners of war during World War II and was decommissioned in 1946. It also served as a training camp for 70,000 soldiers who went on to fight in both the European and Pacific tours.

Taylor’s curiosity about Camp Forrest stemmed from a conversation with her history professor friend, Randy Rosenberg, who said that prisoners of war (POW) had been brought to the United States during World War II.

“I thought he was pulling my leg,” Taylor said, “because all the decades that I was in college, these were things that I had never heard.”

Rosenberg suggested she research Camp Forrest, where his mother-in-law had worked as one of the 12,000 civilian employees during World War II. Taylor said this fact-finding mission became a passion project that has consumed 16 years of her life and counting.

Taylor’s question was how this 85,000-acre facility housed tens of thousands of employees and military trainees, plus over 24,000 prisoners of war, yet there was no catalogue of information about its existence. Taylor knew she had to tell their stories.

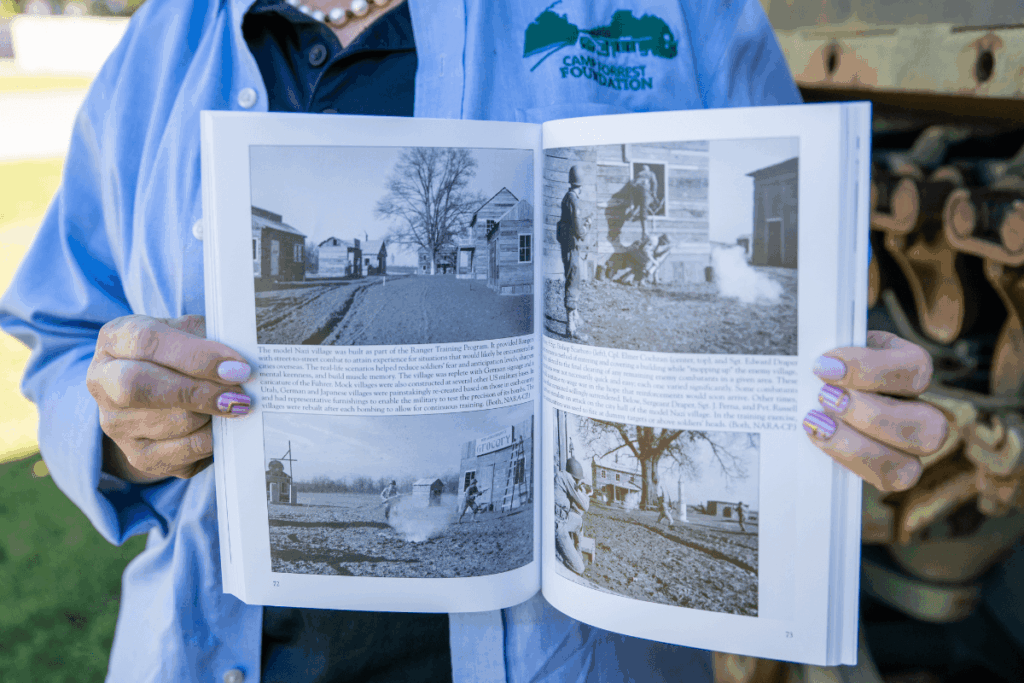

This journey led her to the National Archives in Washington, D.C., where she found a wealth of photographs she used in her first book, “Images of America: Camp Forrest,” published in 2016. Her passion sparked interest, and she had a contract with Arcadia Publishing in just three months.

This published documentation led to Taylor receiving calls from descendants of World War II prisoners hoping to learn about relatives held at Camp Forrest.

“These people worked on farms and made lifelong friends at the camp,” Taylor said.

Prisoners of war at Camp Forrest were allowed to pursue arts and crafts, take college classes, and work jobs. There were occasional escape attempts, but not many, as they were quickly apprehended.

“Being in the middle of Tennessee, there’s not many places to go,” Taylor said.

She scoured libraries, universities, and museums across the country for more information, as documents mentioning Camp Forrest were scattered. At Florida State University, she uncovered more than 60 original drawings created by prisoners of war at Camp Forrest. This artwork had been given to a military police officer and was donated to the university’s collection after his death.

Taylor’s findings give insight into the relationships between prisoners, officers, and civilians. When the first military unit arrived from Chicago, it was the first time Northern and Southern Americans had met up since the Civil War.

“There were stereotypes on both sides,” Taylor said.

Northerners from Chicago expected Southerners to be “slow, lazy, and unfriendly,” but found this largely untrue. Southerners welcomed them, and the Northern transplants returned the courtesy.

The majority of POWs were Germans and Italians brought over after the North African Campaign, but they were treated according to the Geneva Convention, established international rules for humane treatment of prisoners during wartime. This meant they were well-fed, housed, and given opportunities for recreation, education, and employment.

With the male workforce depleted due to deployment, these prisoners filled a crucial economic gap. They worked on local farms, helping plant and harvest peanuts, corn, wheat, and other crops. They made about $.80 an hour, though the government charged farmers $1.50 an hour for their services.

Taylor continued her exploration in her second book, “Voices of Camp Forrest in World War II,” published in 2019. This book focuses on firsthand accounts. Her third book, “Legacies of Camp Forrest,” will be released in November 2025.

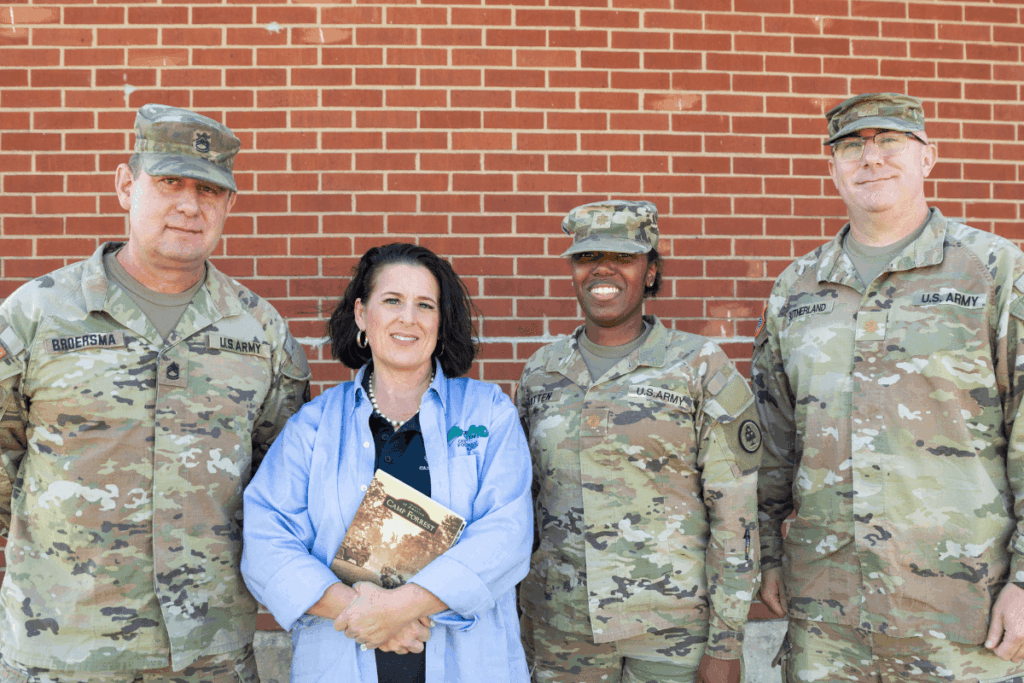

Taylor founded the Camp Forrest Foundation in 2021 to ensure these stories would never be forgotten. This nonprofit organization features a virtual museum showing scanned original artifacts and handwritten accounts. Taylor adds new artifacts biannually, and her efforts have reached people worldwide. She also gives presentations at schools and other groups and teaches history online at Park University and the University of West Georgia.

“I want people to see the humanity, to understand the why, to connect,” Taylor said.

She remembers one fifth grade student at her presentation saying that he hated history but preferred math. Taylor bridged the subjects, explaining how soldiers used mathematical calculations for anti-aircraft guns.

“You could see that light bulb moment,” Taylor said, “and he started to connect with it.”

Taylor hopes to provide more opportunities to learn about Camp Forrest locally as well. Currently, there are only two Camp Forrest signs on site, but Taylor is collaborating with Parks and Recreation Director Lyle Russell to install four additional plaques.

“I just want to make sure that Camp Forrest is not lost to time again,” Taylor said. “The service that these men and women and civilians gave to our nation was too great. We can’t let their voices get lost.”

Taylor never initially planned to champion this cause, but her calling is clear now.

“I tell people I think the universe picked me,” Taylor said. “I don’t know why it picked me, but I’m still doing it!” GN