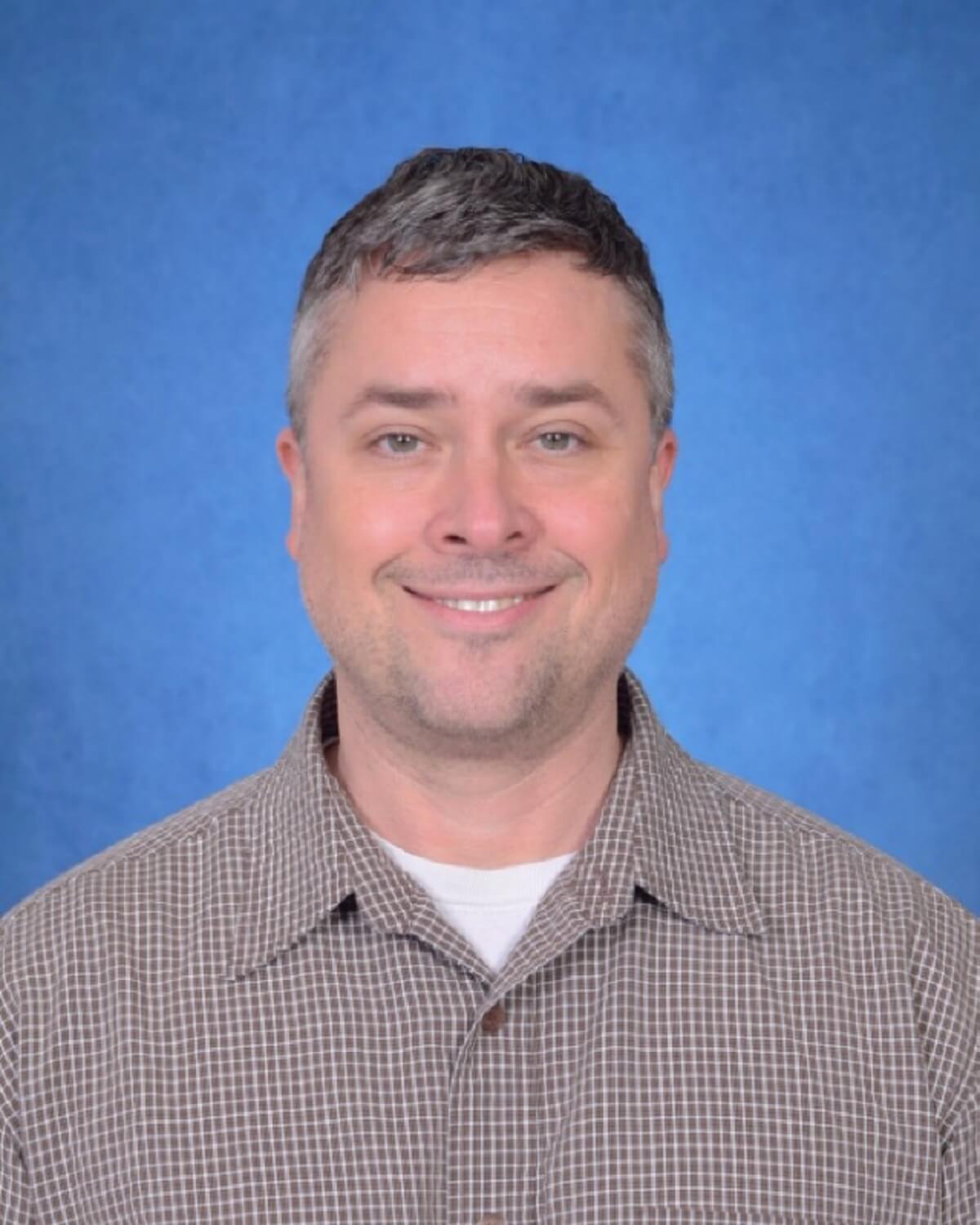

SWEET CORN stalks, reaching for the sun, surrounded Adam Daugherty. Kneeling in the rich Coffee County soil, his hands, accustomed to the feel of masonry tools, held a cob. Daugherty didn’t see himself spending his childhood summers on a family farm, but a successful career in soil science led him here to Daugherty Farms. This oasis captures his passion for healthy land and bountiful crops. Daugherty, a district conservationist with the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), looks to one of our most precious natural resources — the soil, as it holds the key to his agricultural ideology. This is Daugherty’s personal testing ground, where he puts regenerative practices into action, focusing on improving soil health and the environment.

Daugherty grew up on a small farm with horses, cattle, and a vegetable garden in Cumberland County. Beginning at 13 years old, and even while working in the masonry industry, he helped with summer sweet corn harvests, only intensifying his interest in growing things. These early beginnings in agriculture and a lifelong appreciation for the outdoors and ecological systems set the stage for his future career.

“I grew up riding horses, and I had a grandmother who had horses and always had a few cattle, chickens, and everything else in the yard running around.”

“I always had a knack for putting a seed in the ground and watching something come from it. And I’ve always appreciated how nature was designed to work and how everything was synergetic.”

Though Daugherty initially pursued veterinary medicine, his love for the science behind plant growth led him to a degree in plant and soil sciences from Tennessee Tech University. He then earned a master’s in biosystems engineering technology at the University of Tennessee, focusing on the management of animal waste. This expertise eventually led him to the United States Department of Agriculture’s NRCS.

Working with NRCS since 2002, Daugherty has focused on promoting voluntary conservation practices with private landowners. He’s particularly passionate about soil health, a concept that focuses on the biological aspects of soil and its role as a living ecosystem. This new knowledge opened the doors to transformation, both professionally and personally.

Returning to Coffee County as a district conservationist, Daugherty was determined to see if soil health practices truly worked. He established Daugherty Farms as a personal experiment. He could introduce new cover crop species, no-till farming, and other regenerative methods on his own land, allowing him to learn from failures without impacting the farms he advised.

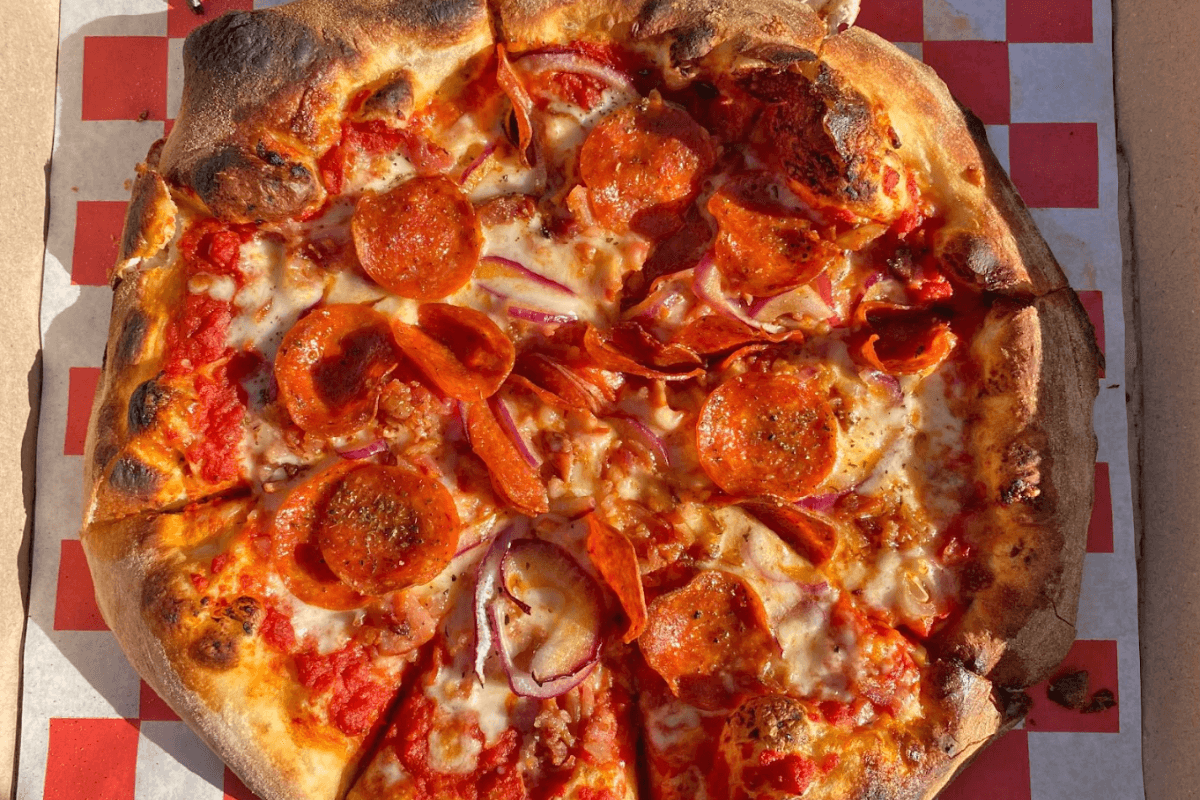

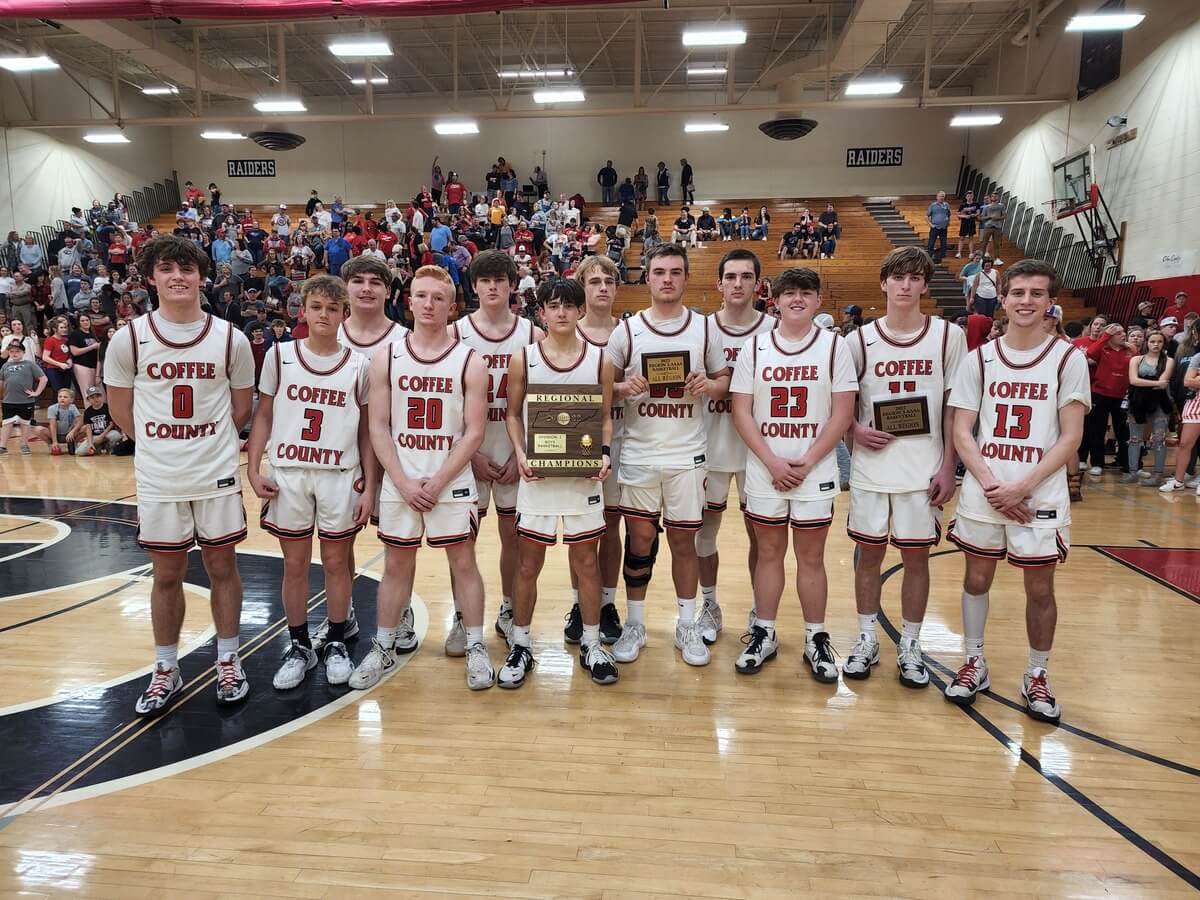

While corn and soybeans are Coffee County’s staples, Daugherty opted for sweet corn for his farm. It required intensive management, making it a valuable learning tool. His goal was to demonstrate the effectiveness of regenerative practices on a high-maintenance crop and to provide his sons with hands-on agricultural experience. The Daugherty sweet corn is now a fixture at local farmers markets.

Coffee County is a leader in the large-scale adoption of regenerative practices. Over 99% of its cropland uses no-till methods, and more than half incorporates cover crops. Daugherty attributes this success to collaboration between the NRCS, the local Soil and Water Conservation District, and the dedication of area farmers.

“I figured if I could manage a sweet corn crop in some of these regenerative scenarios, we could take that knowledge and put it into other crops. Plus, it was a way for the boys to start setting aside money for their future.”

Embracing nontraditional farming methods presents exciting opportunities along with some challenges. In the past, abundant and affordable fertilizers were the norm, but tilling the soil disrupted the natural balance of plants and microbes. Transitioning to more natural processes involved a learning curve and paradigm shift as he sought to understand the ecosystem better.

Despite the initial challenges, the rewards of nontraditional farming methods are plentiful.

“You can restore the soil to a fully functioning, living ecosystem and restore its natural nutrient cycles,” he began. “The beauty of regenerative farming is we can use these tools that we have on hand. We can work with nature and capture the benefits that she provides. We could also keep a lot of diversity in our fields and minimize the disturbance.”

Regenerative farming also benefits our environment as a whole.

Daugherty said, “We can keep our water clean, we can keep our air clean, and even if you’re not farming on the farm, it has direct benefits downstream to everybody in the community.”

For Daugherty, the farm-to-table movement is vital. It educates consumers about the origins of their food and empowers communities to be more self-sufficient.

Daugherty’s vision for Coffee County’s agricultural future is for every field to be continuously covered with plants and a year-round living plant growth strategy. He also envisions the county becoming a focal point for corn, soybeans, and a wider range of crops grown using regenerative methods. He aims to attract smaller producers focused on farm-to-table ventures, creating a diverse agricultural landscape.

Despite his broader agricultural interests, Daugherty remains a sweet corn enthusiast. His favorite way to enjoy it is by boiling it and throwing in a stick of butter. He is constantly testing new varieties and using adaptive management techniques to maximize sugar content.

Daugherty Farms regularly attends farmers markets in Coffee County, Warren County, and Lascassas and sells directly to customers. It is also expanding into winter produce production with a new high-tunnel greenhouse.

He said his wife, Jaime, and two sons, Brady and Tanner, are integral to the operation in all aspects, including variety selection, marketing, and sales.

The essence of his message is clear: “Healthy soil leads to healthy food, farmers, and communities.” GN