Growing up in a world of unpredictability, where stability was a luxury and trust a fragile commodity, was the reality for Mary Hazelwood. As a child, Hazelwood experienced the instability of the foster care system, moving between two homes for a year before her father regained custody. Through this tumultuous period, though brief, Hazelwood found the strength to rewrite her story. Today, as a forensic social worker, she spends her days unraveling the complexities of the criminal justice system as part of the criminal defense team, giving clients hope and a path toward a brighter future.

While Hazelwood now loves her work, her childhood was so chaotic that she couldn’t imagine being in her current position.

“My childhood was so chaotic and dysfunctional that I really couldn’t dream of anything,” she said. “The instability led to me being placed in Department of Children’s Services (DCS) custody for some time.”

She didn’t know it then, but her time in DCS custody would soon become the unexpected key to unlocking her dreams.

“It was while in DCS custody that I first met a social worker who made a lasting positive impression on me,” she said.

With the pieces of her childhood and the inspiration from that social worker, Hazelwood began to write a new story. But fate had other plans, and her journey took another unexpected turn. At age 24, while working maintenance at a factory, she suffered a work accident that almost took her life.

“I had to be revived in the ambulance, LifeFlighted to Vanderbilt, and then put into a medically induced coma while I recovered from a traumatic brain injury,” she recalled.

After numerous surgeries and years of rehabilitation, Hazelwood was finally healthy enough to pursue her education in 2018. She enrolled at Motlow State Community College for her associate degree in social work, then transferred to Middle Tennessee State University for her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in social work, with a new dream — to help others as a social worker once helped her.

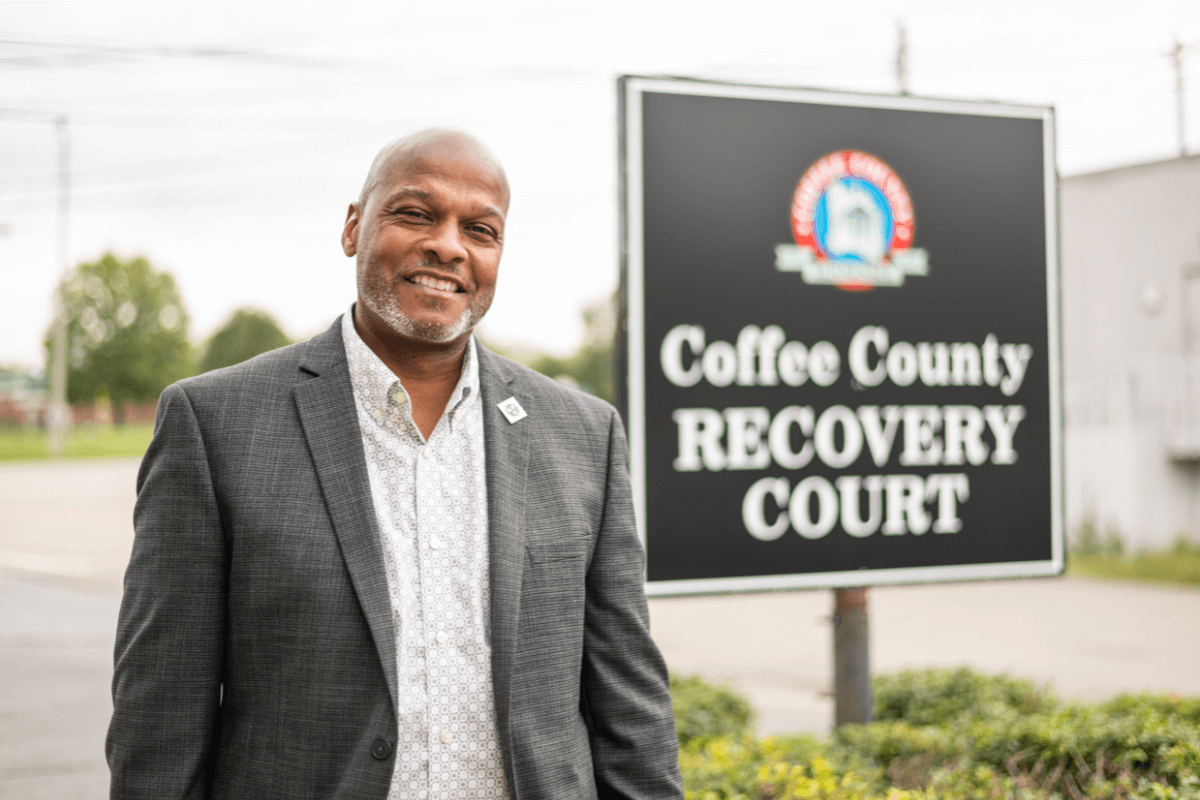

Hazelwood said her decision to pursue social work, especially in the criminal justice system, felt predestined. One of the requirements for her bachelor’s degree was a 400-hour internship. When the internship she had lined up fell through at the last moment, her field advisor recommended the public defender’s office in Coffee County.

“Without any other options, I decided to apply,” she admitted.

Initially, Hazelwood imagined working with children or becoming a victim’s advocate, so the idea of working with adults facing criminal prosecution didn’t seem appealing.

“I went into the interview with absolutely no idea what a social worker would do in a public defender’s office or whether I would be a good fit,” she said.

However, as she interviewed with John Nicoll, the district public defender in Coffee County, his vision for the social work program moved her.

“It’s now four years later, and I have fallen in love with this work,” she said. “I’ve learned what a positive impact I can have on our clients’ lives by helping them overcome adversity and rewrite their own stories just as I did in my own life.”

Hazelwood can’t imagine doing anything else. Making a difference in her clients’ lives is her morning fuel, resources that can impact their and their family’s well-being.

She spends her days between the jail, the courtroom, and her office, reviewing medical records, conducting client assessments, and coordinating services. She listens to clients’ success stories with a sparkle of excitement in her eyes. The pride of watching her clients achieve something they didn’t think was possible feels invigorating.

Most of Hazelwood’s clients have faced more adversity than anyone should ever experience.

“Many clients are in the criminal justice system because they are battling substance abuse, mental health issues, homelessness, or unemployment,” she explained.

Each success reminds her and her clients that they don’t have to face this seemingly grueling process alone. This collective success benefited individual clients and also enhanced the quality of the broader program.

Together with her team at the public defender’s office, Hazelwood has helped the social work program grow considerably. The initial stages were challenging, but now the office serves as a prototype for best practices in rural districts statewide.

“There were growing pains at first,” she said. “We didn’t have established models to replicate in rural communities, and it took time to educate other stakeholders in the criminal justice system about the role of a forensic social worker.”

Since then, Hazelwood has contributed to interprofessional collaborative training for staff in 13 other districts, hoping to expand the use of forensic social workers across Tennessee.

Aside from the training programs, Hazelwood finds her greatest reward is witnessing the personal transformations her work supports. She is especially proud of three clients who, after completing treatment programs, now work as peer support specialists or house managers, helping others on their path to recovery.

“People can’t change the past, but they don’t have to be defined by it either,” she said. “If I can help clients find their inner strength to make positive changes, our community improves, one client at a time.”

In the future, Hazelwood hopes to continue expanding forensic social work in public defender offices across the state. She plans to grow the internship program and eventually develop a curriculum to train future forensic social workers.

Hazelwood’s story has evolved from the depths of uncertainty and disarray into a source of inspiration for many. Her trials have given her the insight and strength to help others learn to dream again and rewrite their stories. She has proven that healing and hope are always possible, no matter how bleak the path may seem. GN