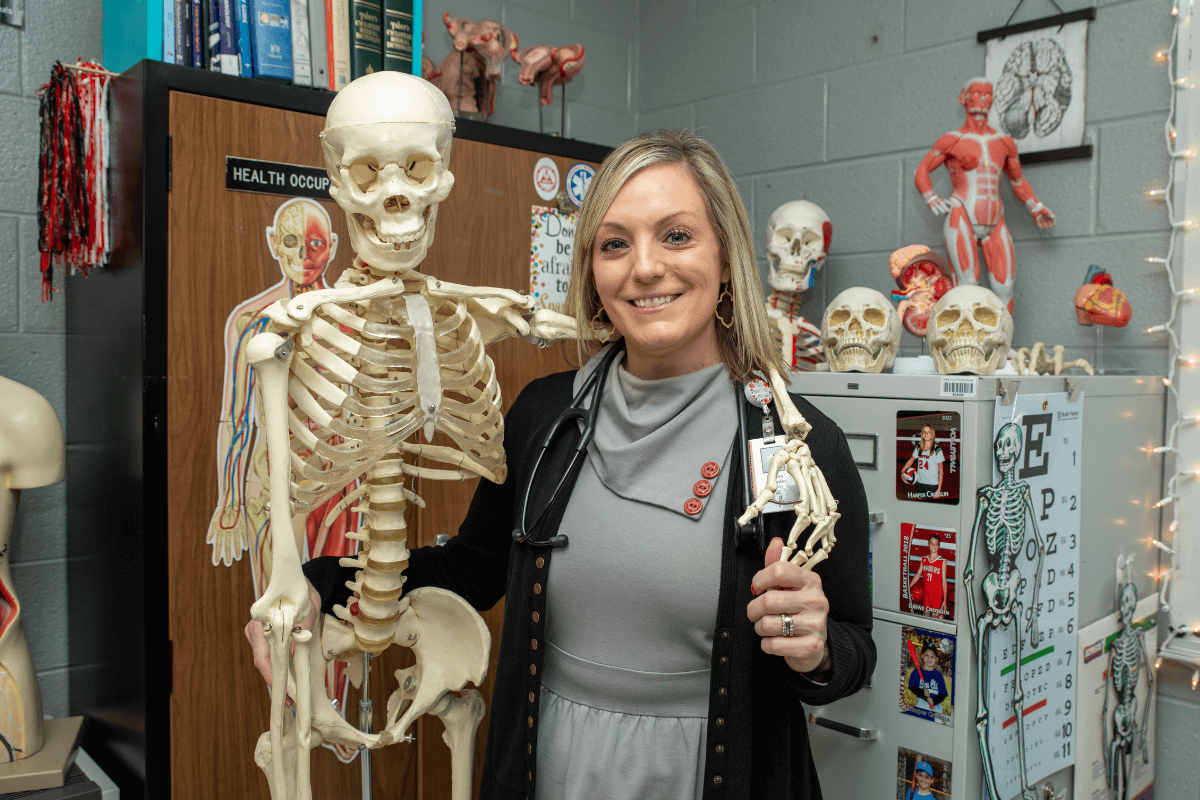

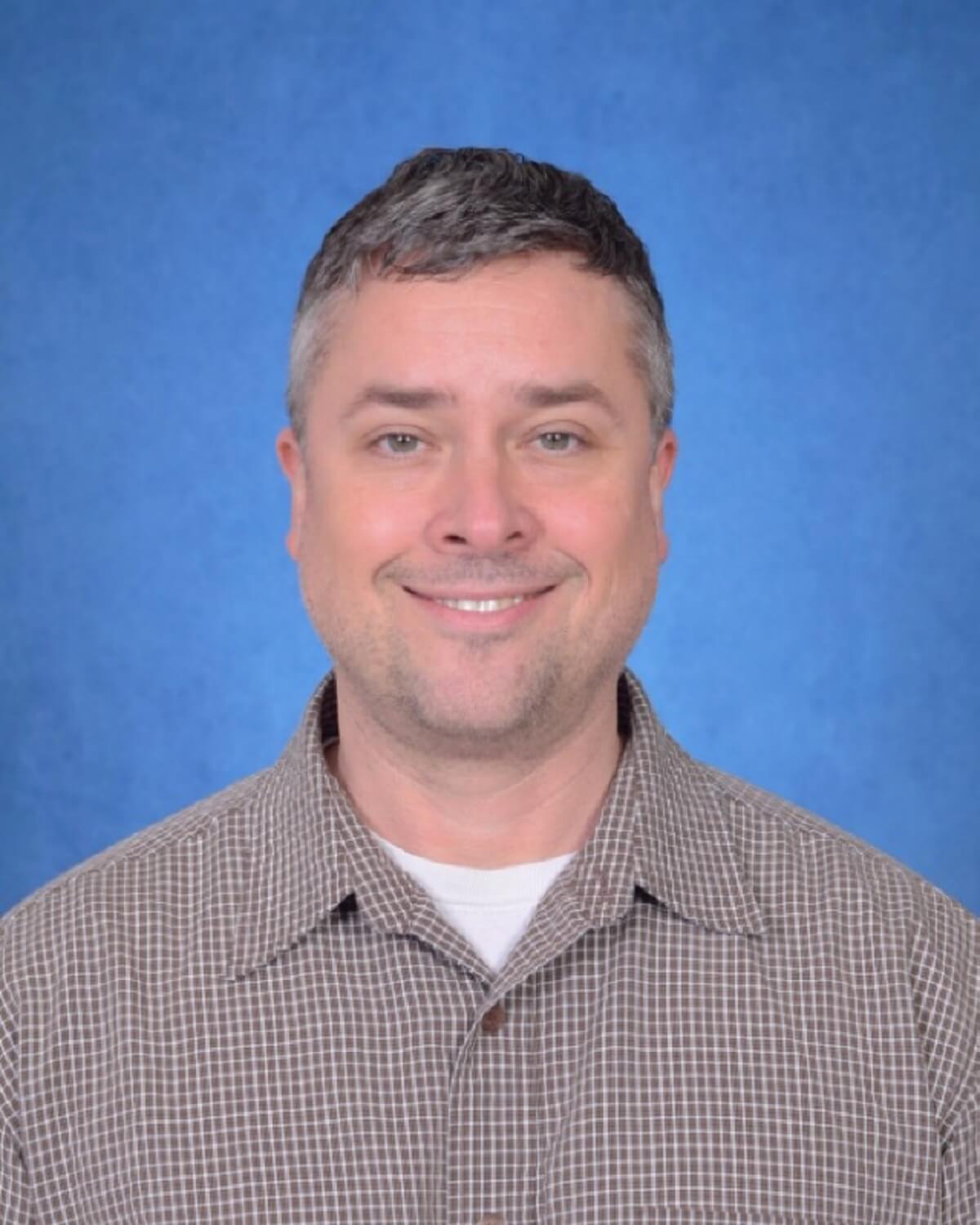

At Coffee County Central High School in Manchester, students are discovering more than just animal care — they’re discovering themselves. Behind that transformation is Kim Miller Parker, a career and technical education (CTE) advisor whose 23-year career has been devoted to helping young people grow confident, capable, and community-minded through agricultural education.

In the classroom — and sometimes even in the barns and fields — she teaches small and large animal care and veterinary science to high school students, some of whom have never been around animals at all. While many schools focus on core academics, Miller Parker’s classroom teaches technical, professional, and life skills that are vital but often overlooked.

“I want them to have the self-confidence to pursue what they want,” she said. “I want them to be able to speak in public, honor responsibility, and explore their options instead of being boxed in by the time they’re in eighth grade.”

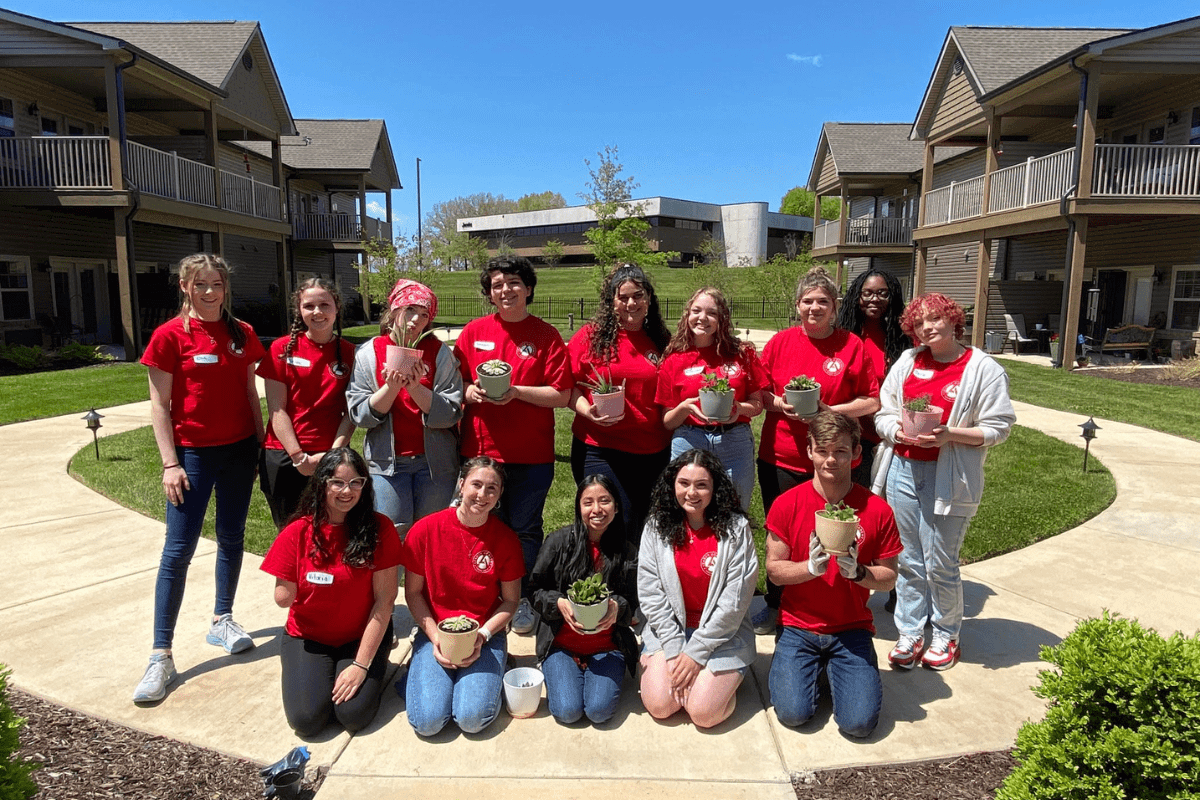

Through public speaking competitions, many hosted by reputable organizations such as the National FFA Organization (FFA), her students have won national recognition. Leadership development is included in everything they do. Students attend school board meetings and farm bureau gatherings and even have the opportunity to travel to Washington, D.C., for leadership conferences.

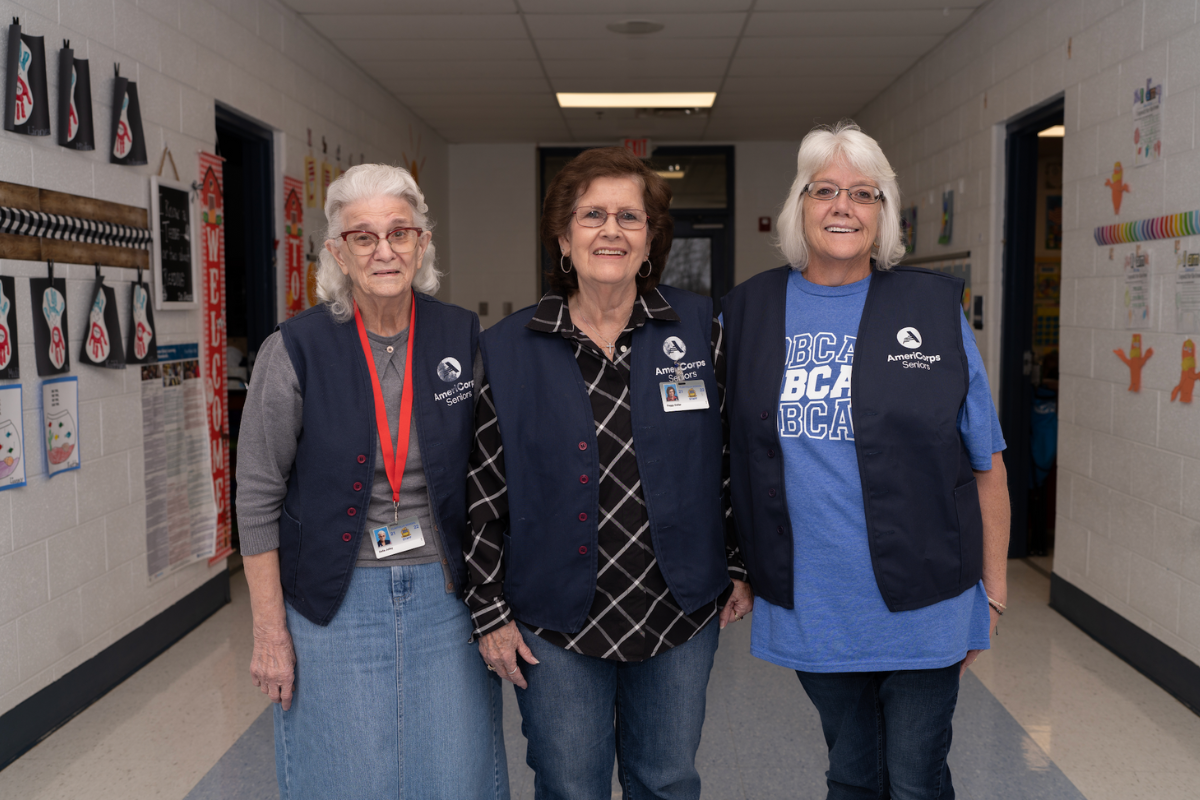

“We do a lot of community service, too,” she said. “We participate in FFA’s Passing Literacy OnWard program, which promotes reading literacy and agricultural education for younger students. That helps our kids develop communication skills and connect with the next generation.”

For many students, Miller Parker’s program is their first exposure to animals beyond household pets. Her courses in small and large animal care introduce students to everything from guinea pigs and chinchillas to dairy cows and show horses.

“We have students who come in never having stayed overnight away from home,” she said. “By the time they’ve been in the program, they’re traveling, competing, and stepping into leadership roles.”

Some students who don’t have the space or resources to raise livestock are invited to join show teams organized by other students’ families.

“It gives those kids hands-on experience and teaches them what it really takes to care for another living being.”

The progression is intentional. Most students start with small animals and gradually move up to more intensive responsibilities. By the time they reach the veterinary science track, they’ve already logged two to three years of animal care experience.

“We start with Latin terminology, injections, dosage calculations, and then move into how to interact with clients and what’s legal and ethical for vet assistants,” she explained. “It’s a rigorous curriculum.”

This year, Miller Parker’s class is piloting a new program through Texas A&M University that allows students to graduate with a Veterinary Assistant Certification. To qualify, students must complete 300 hours in the classroom and 225 hours of hands-on veterinary experience — either paid or unpaid — before taking the final certification exam.

“It gives them a solid entry point into the workforce right after high school,” she said. “From there, they can choose to pursue a two-year vet tech degree, go on to a program like the one at [University of Tennessee at Martin] that’s similar to a nurse practitioner, or eventually attend vet school.”

The multiple pathways are designed to meet students where they are and support them as far as they want to go. Some alumni have become veterinary technicians, teachers, insurance agents, and even government employees. Others work as seed representatives or extension agents.

“The ones who really dive in eventually build careers in the industry,” she said proudly.

What stands out most about Miller Parker’s teaching philosophy is her deep commitment to personal growth. She realizes that it isn’t just about teaching about the animals; she ultimately is teaching students how to navigate the world with courage.

“Some kids don’t even know how to order food in a restaurant when they start here,” she said. “But you take them on small day trips, encourage them to compete, and they blossom.”

One of her students, once too shy to stay overnight away from home, went on to study abroad in Costa Rica and serve in the student government at Tennessee Tech. It’s moments like that that remind her why she does this work.

“I want them to come back to their communities and be leaders,” she said. “We have a lot of transplants here — people who move in and want to change things. But I want these kids to grow up respecting what’s already been established here and contributing in ways that honor that.”

“I’ve been doing this long enough now that I’m starting to see the full circle,” she said. “And that’s a good feeling.” GN