THE DECISIONS and actions of past generations shape Lincoln County and Fayetteville’s landmarks, institutions, and culture. Though they are no longer here, their work, even down to their smallest decisions, left a lasting impact. Their stories and legacies continue today as a vibrant thread in the tapestry of our community, and their influence can be seen in every corner, silently testifying to their commitment to improving the lives of all around them.

Dr. Cecil E. Byrd is among the many who quietly and positively contributed to our area’s quality of life.

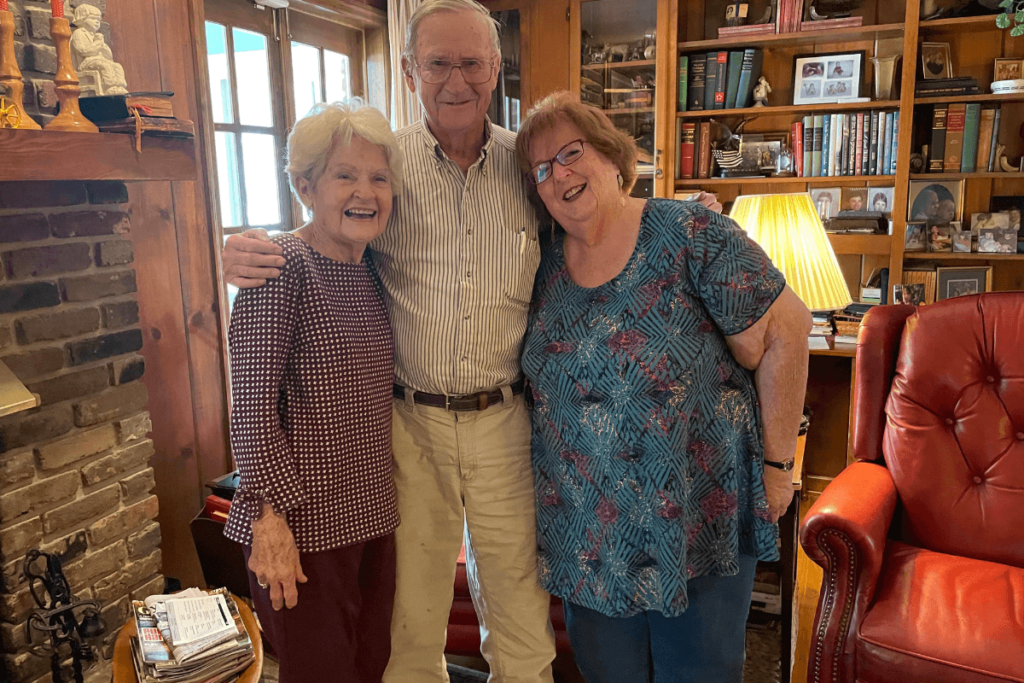

The young veterinarian, a Texas native, moved to Fayetteville in 1944 with his wife, Lucille, and their 1-year-old daughter, Patty. The city’s sole vet, Dr. Ross Whitaker, had passed away a few weeks earlier. Although he’d planned to work with Dr. Whitaker upon his arrival, his plans soon changed, and he established the Fayetteville Animal Clinic across the street from today’s Cahoots.

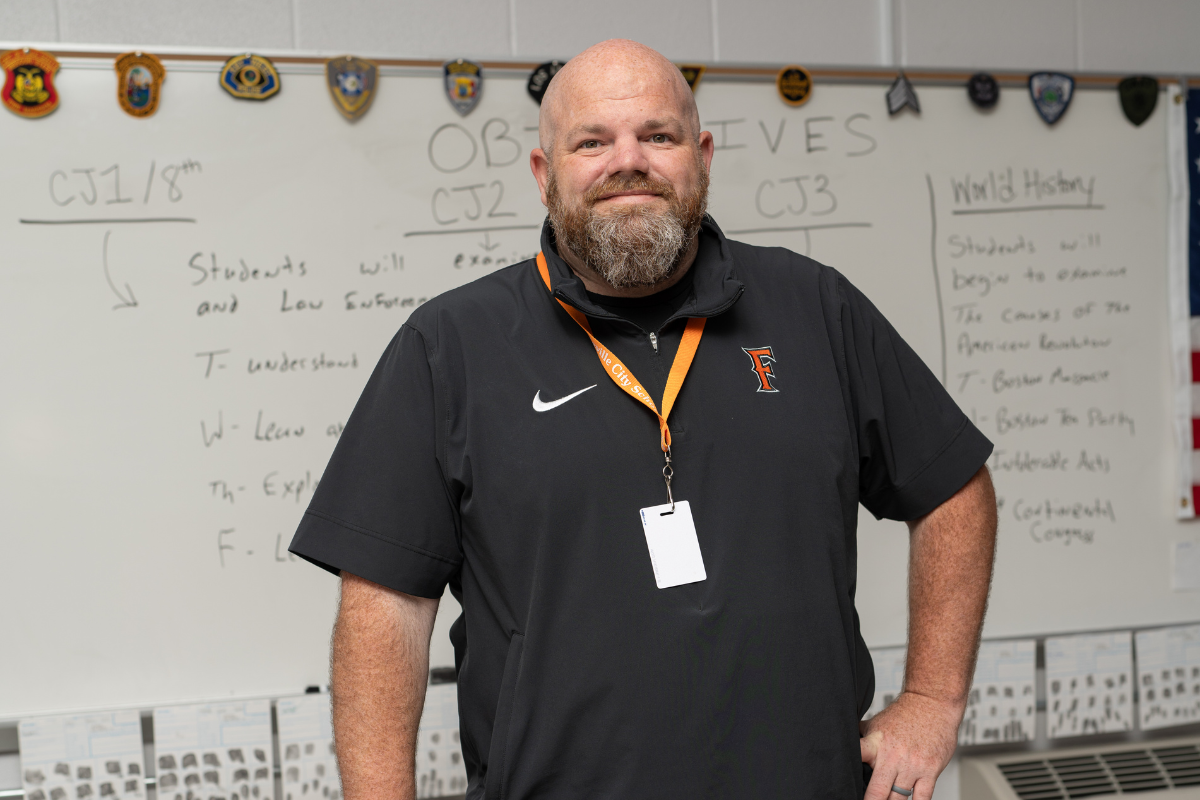

Dr. Farris Beasley joined Byrd and Dr. Tom Bullington in the practice in 1959.

“We had [more than] 250 Grade A dairies in Lincoln County. We covered Lincoln, Moore, and Marshall Counties and all the way down to Huntsville. He was a very conservative businessman who taught us to be conservative. We didn’t waste a lot of money on frivolous things, and he was a good teacher for us in that respect. Dr. Byrd was a great veterinarian and a really good physical diagnostician. He could quickly figure out what was wrong, and I learned an awful lot from him. He was a great man,” said Beasley.

Seven doctors were on staff when Byrd retired, and the clinic has relocated twice since Byrd established it on Fire Hall Hill. Fayetteville Animal Clinic is one of the largest veterinary clinics in Tennessee today.

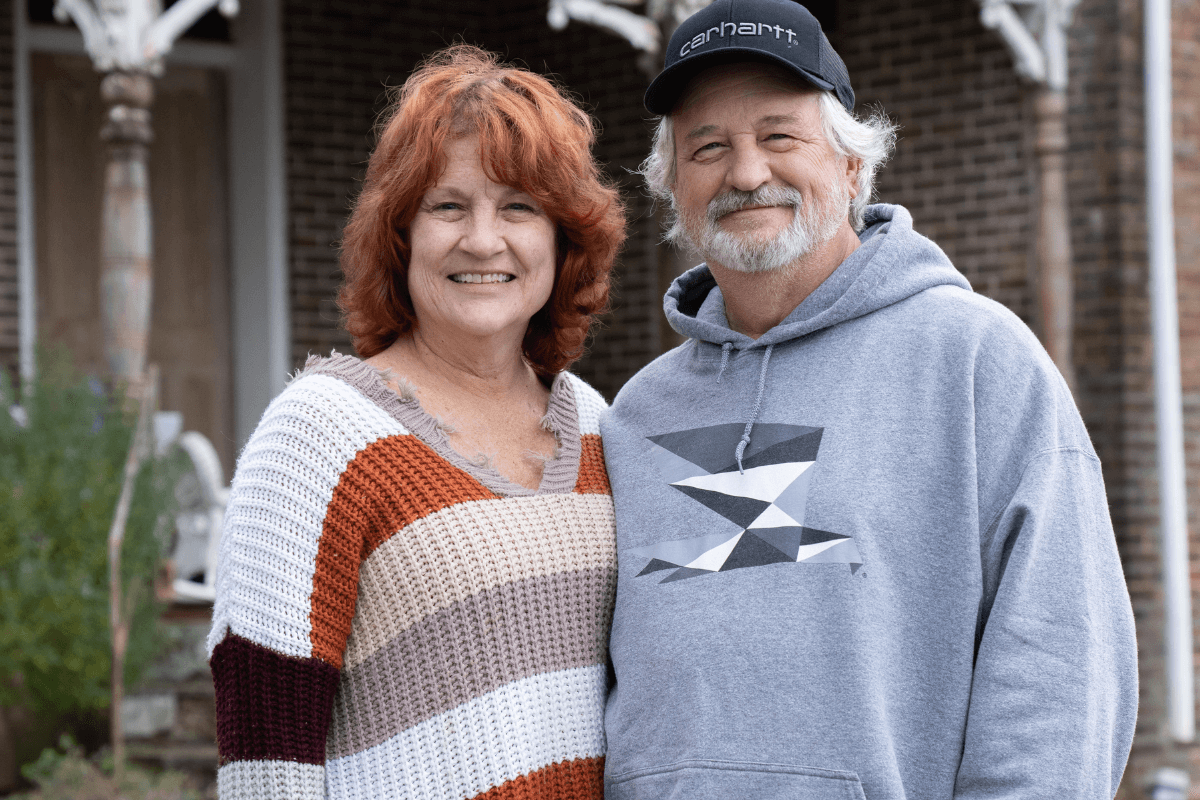

“He just loved all animals,” said Byrd’s daughter, Bonnie. “A lot of our pets growing up were mostly from farmers who couldn’t pay their bills. They’d say, ‘Doc, I just don’t have the money. See if you can find a home for it.’ So we got a lot of our cats and dogs that way, and we even got a cow named Brownie, who was, of course, Brown,” said Bonnie. “But the man said, ‘If you take Brownie, you have to take Lulu, the donkey because they’ve grown up together, and I can’t separate them.’”

And so the cows would find a home on whatever farm Byrd owned at the time or in their pasture located at their home on West Washington/Highway 64. Bonnie remembered the police calling once in the middle of the night.

She said, “The officer said, ‘Doc, we think your cows got out because they’re walking the center line on Highway 64 heading toward your house. So Mother and Daddy both got in their cars, and one pulled in front of them and one at the back of them with their flashers on. I remember I stood there for the longest time with the gate open to our pasture, waiting for the cows to come home.”

Byrd’s passion for the animals in his care enabled his three daughters, Patty Byrd Fuquay, Cecilia Byrd Harris, and Bonnie Byrd, to obtain college educations.

Bonnie said, “It isn’t until your parents pass away that you realize how fortunate you’ve been. Daddy was a great businessman. He’d buy a farm and have a family who needed a home to live there and work the land. After four years, he’d sell it, and that would be our college money. A year later, Daddy would do it again for the next girl’s college money. That’s one of the many things he did for each of us.”

Byrd, a Fayetteville Alderman for many years, was known as a straightforward man who stuck to his word.

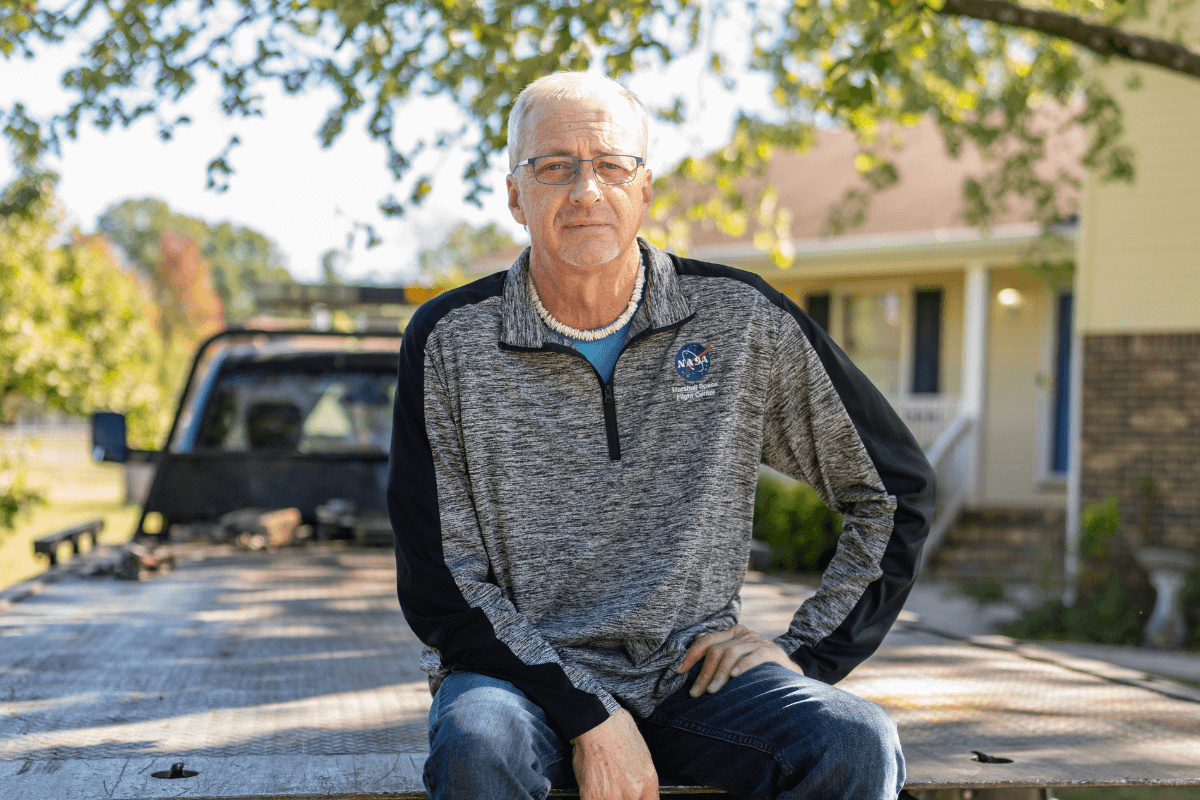

John Ed Underwood served as an alderman in Byrd’s final terms and alongside him on the public works committee.

Underwood said, “I enjoyed working with him, and I think anyone that worked with him appreciated him because he was a straight arrow.”

Byrd was the airport board chairman for many years, and although he was not a pilot, he was always fascinated with flying.

Bonnie said, “He was always interested in planes. If we passed a small airport, he would pull in so we could watch them take off and land. He never pursued taking lessons, but he subscribed to an aviation magazine and loved it.”

During his time on the airport board, an empty peach tree field became the Fayetteville Municipal Airport, and the airport authority named the field in his honor after he died in 1991. His passion for flight contributed to a boost in economic development, tourism, emergency response, flight education and training, and recreation — an overall improvement in the community’s quality of life.

Wouldn’t he be proud to know his grandson, Todd Harris, Cecilia’s son, is a pilot for Southwest Airlines today?

The influence of previous generations may not always be easy to see, but it’s always there, shaping the cities we live in and the lives of its residents for tomorrow. GN