JOHNNY DEPP said, “My body is my journal, and my tattoos are my story.” American tattoo artist Kat Von D agreed when she said, “I am a canvas of my experiences; my story is etched in lines and shading, and you can read it on my arms, my legs, my shoulders, and my stomach.” And Michael Biondi, also a tattoo artist, said, “Our bodies were printed as blank pages to be filled with the ink of our hearts.”

A journal, blank pages, a canvas… stories, experiences, heart… Regardless of the mediums we choose to express our stories, the common thread is people.

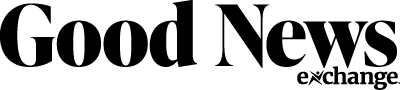

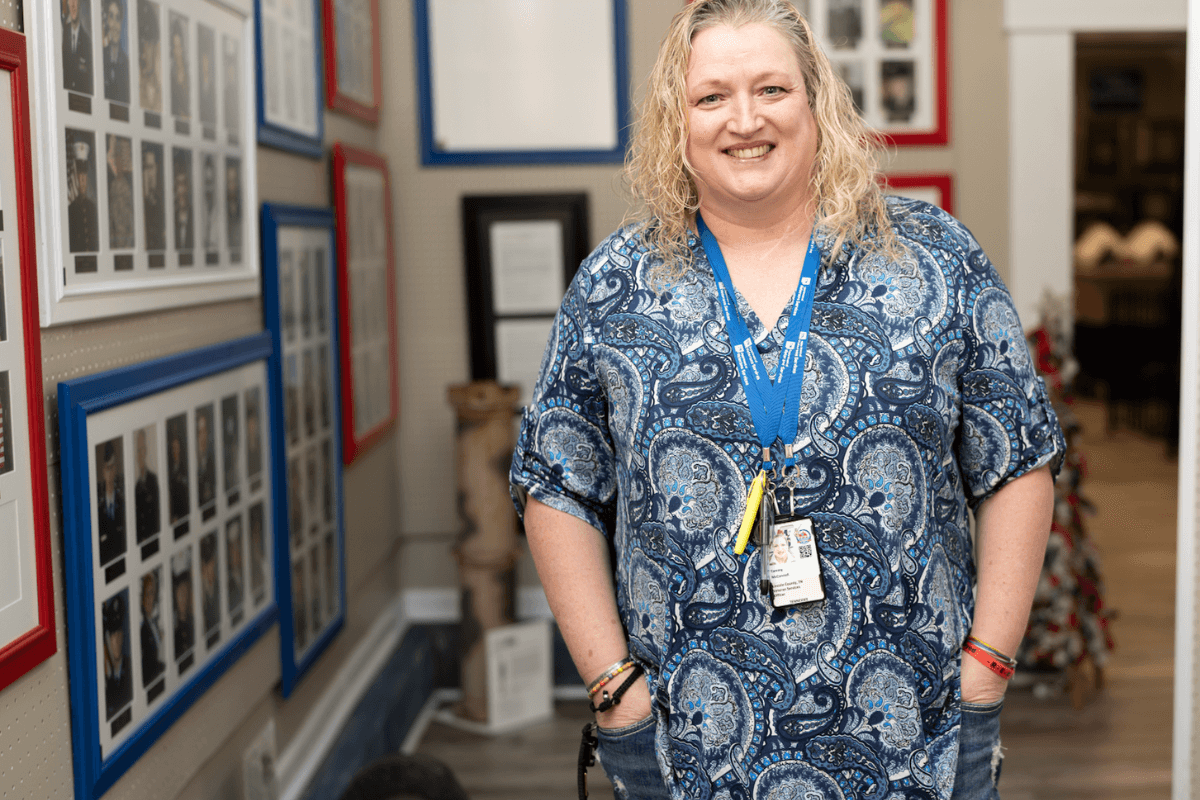

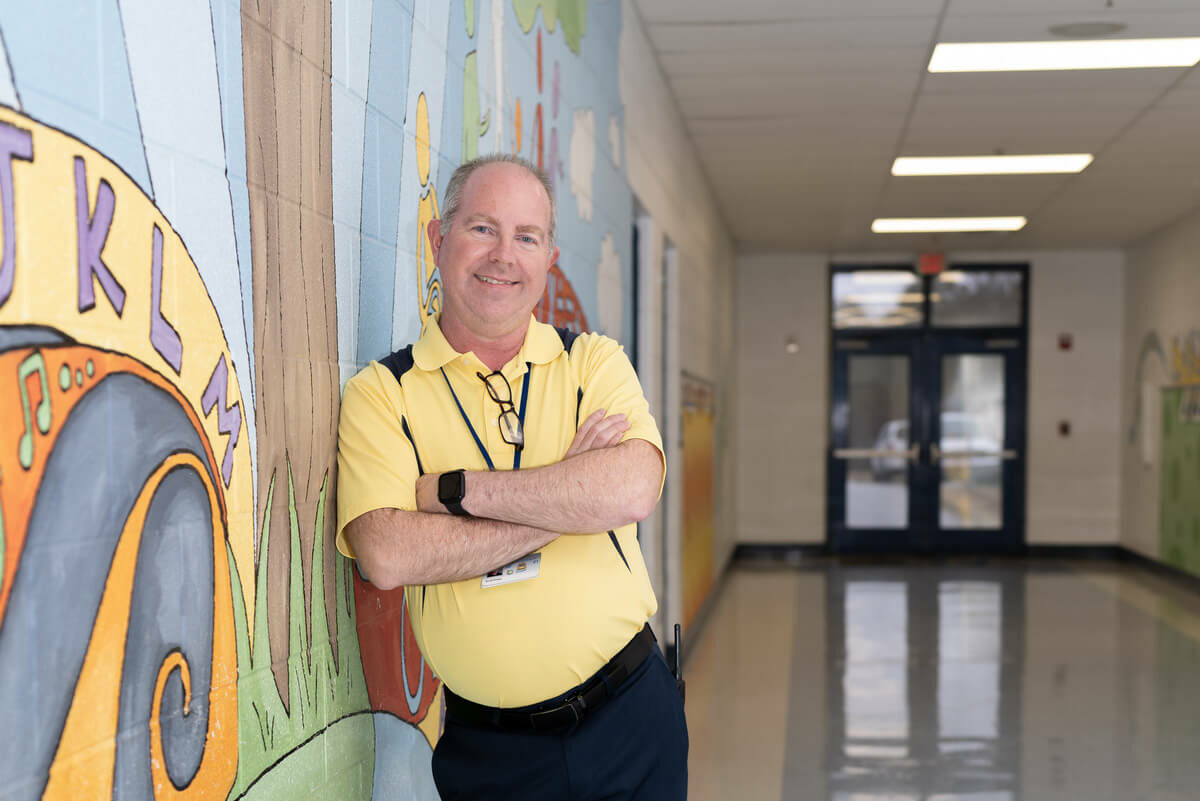

Flintville’s Keith “Booda” Pierce illustrates everything from great joy to the most profound sorrow on his customers’ canvas of choice — their bodies.

Pierce’s Lincoln County childhood included things common to everyone else’s, except a love of drawing was always present.

He said, “No one’s ever taught me how to draw. I’ve always just followed the path wherever the pen took me. I was way more interested in drawing and comic books than football, and my dad couldn’t understand why I drew all the time. I told him it’s just what I do.”

Like most parents, his dad wanted the best for him and saw only a world full of starving artists and told him he’d end up as a tattoo artist if he didn’t watch it.

“Today, my dad is my biggest fan. He shares my work all the time. He’s awesome.”

But the path of the pen didn’t lead straight to Lost Highway Tattoo Studio and the space he shares with artist Jermain Simmons. Pierce worked several jobs following high school, one at a Fayetteville liquor store. When things slowed on his shifts there, he drew without thoughts or ultimate purpose beyond passing the time until the evening when a customer asked if he could keep his drawing.

“I went home, didn’t think anything of it. I came back to work the next afternoon, and there was a business card from Addiction Tattoo, the first tattoo shop in Fayetteville. [The gentleman at the liquor store] had given my drawing to [the owner], Robert Wellman, and Robert called and asked if I’d like to come in and check it out and see what it was like,” Pierce said.

He was 29 at the time, terrified and intimidated as he watched the artists use needles and ink to trace lines from which intricate designs emerged.

“It was weird to see. The customers weren’t crying, and it freaked me out, seeing so much art put on people,” he said. “I struggled with it for a long time but eventually just settled in, and I couldn’t imagine doing anything else.

Following Addiction Tattoo, Pierce worked at Raining Ink in Columbia but dreamed of working for himself. He opened Lost Highway in Pulaski in 2011, then the path of the pen etched his way home when he opened Lost Highway in Fayetteville in 2012.

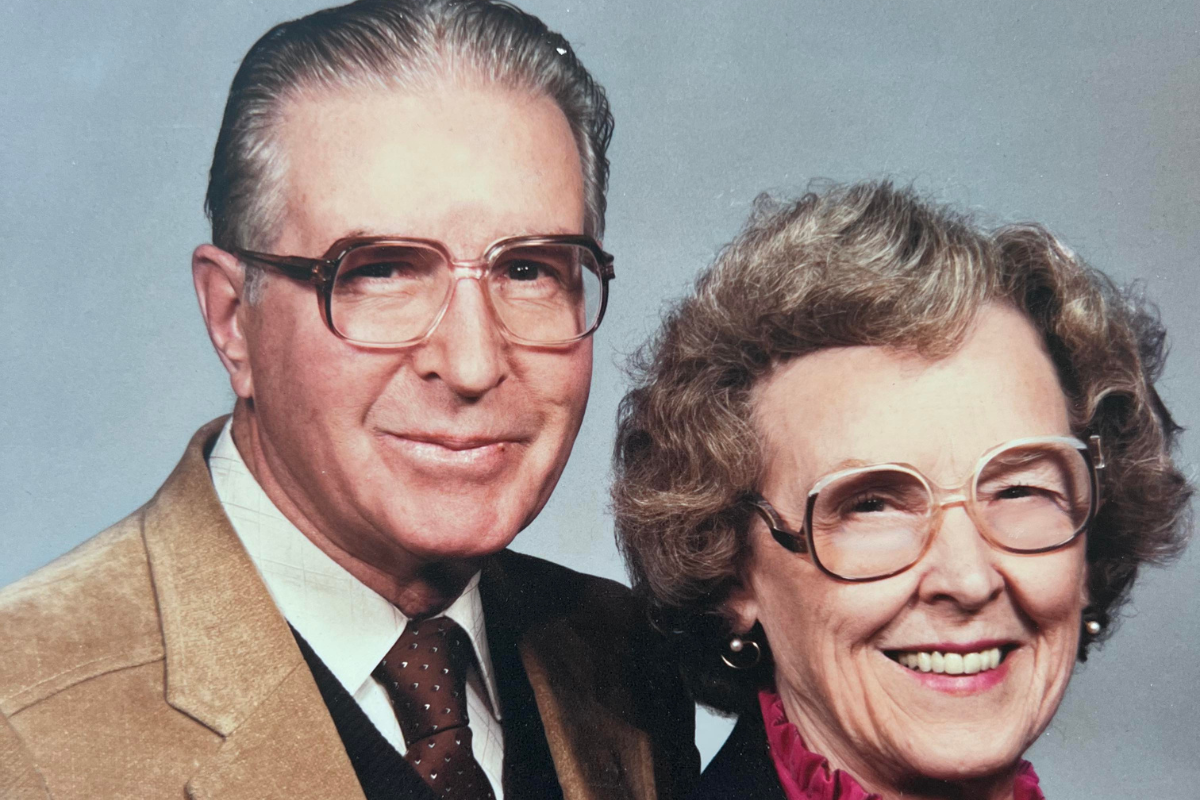

It’s an art that has grown in popularity and now spans generations and socioeconomic groups. Everywhere you go, you glimpse inked images engraved on canvases of skin representing love, loss, hobby, hope, fascination, and obsession. They are small and unseen on many you encounter daily and large and detailed on others. They are personal and often represent transition, growth, and revelation.

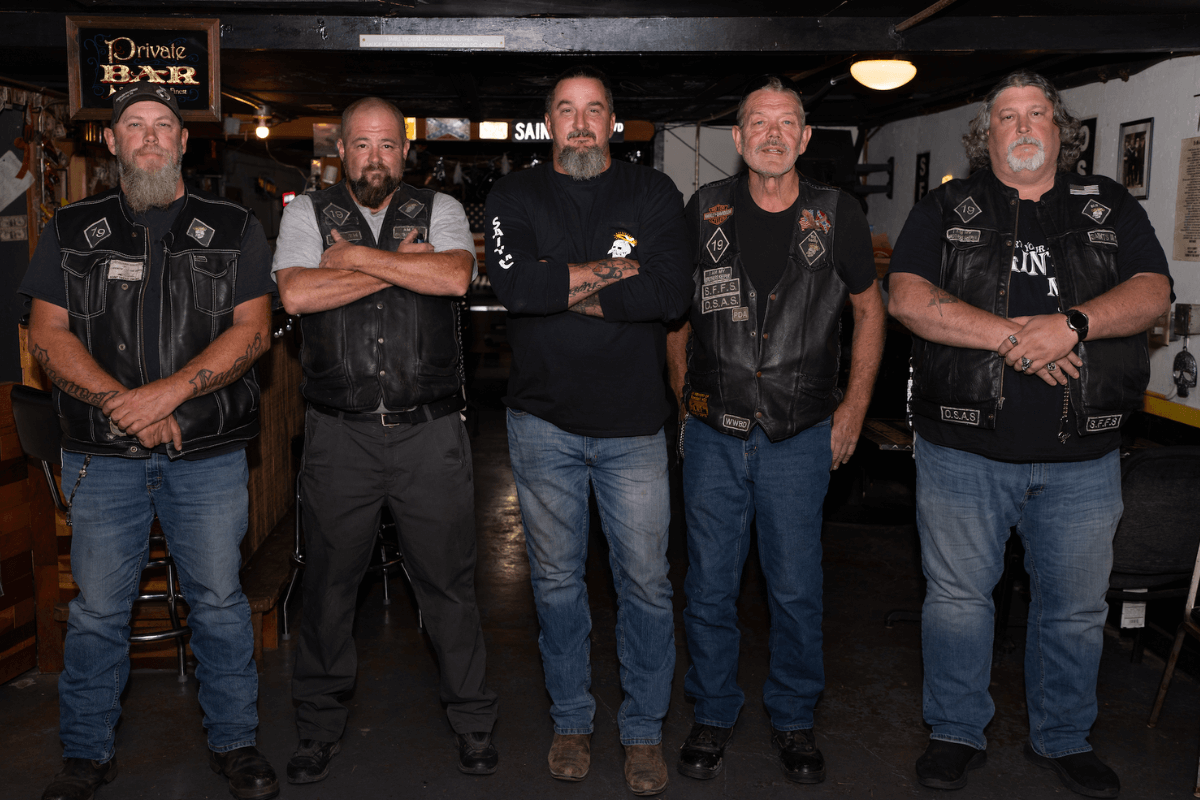

“When I started tattooing, I didn’t tattoo as many older people. It did happen, don’t get me wrong, but “Ink Masters” [reality show] hadn’t started yet,” he said. “Then, if you were tattooing older people, they were generally bikers, old cowboys, or old truckers. “Last Man Standing’’ was also a pretty good show. America loves competition. Those shows got really popular, and the next thing you know, we have little ladies coming in for butterflies on their feet, and it’s gone from there.

Tattoos are more common today, but, like all art, they’re not for everyone. However, unlike most art, they are sometimes viewed in a less than favorable light.

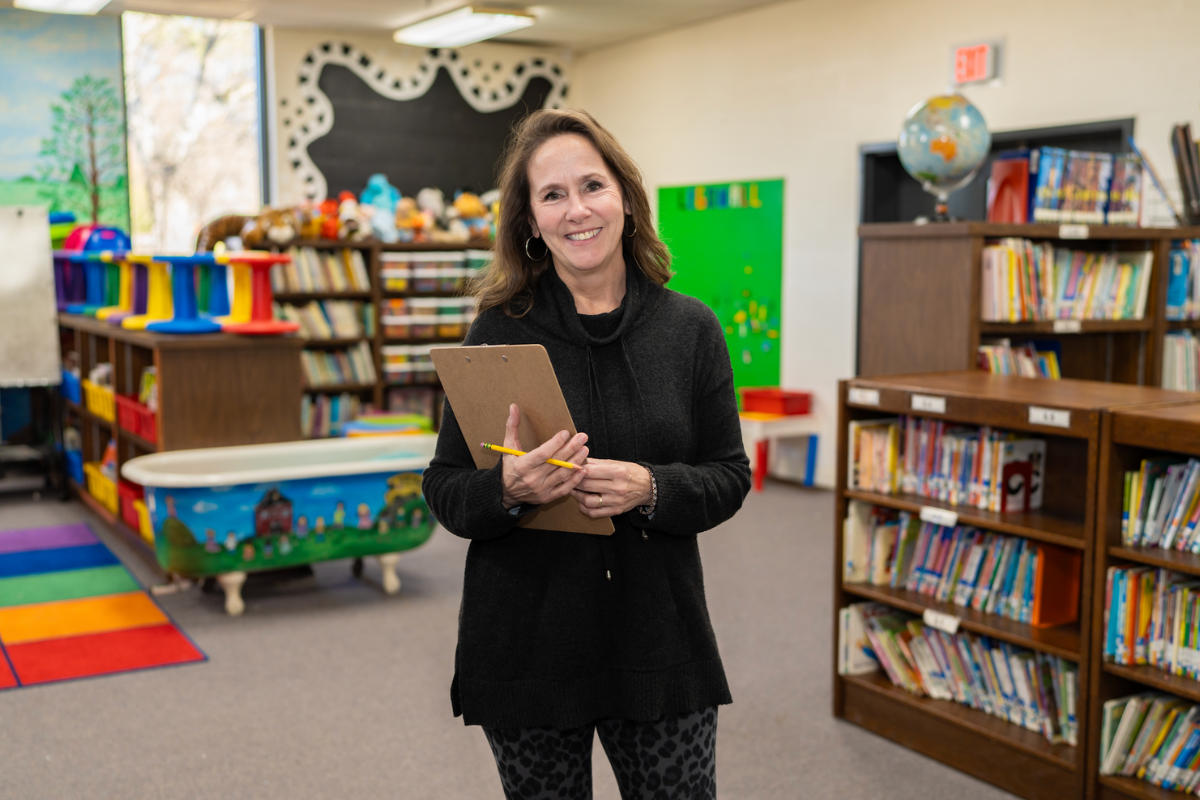

Pierce said, “Tattoos don’t make you a bad person, and that’s a big thing. There are doctors with sleeves and nurses with tattoos. Lawyers and teachers get tattooed.”

And his favorite thing about his work is the people.

“Different people come in every day, and I get to talk to them and cut up with them in a different way,” he said. “If somebody’s sitting there, and they’re not comfortable, or they’re hurting, I can start talking to them. It will still hurt, but talking makes it better. Or if they’re talking way too much and getting anxious, I can calm them down. The worst thing you can do when you come is be nervous.”

If Pierce could go back today and speak to that little boy who loved drawing, he’d tell him, “It’s gonna be okay. Yeah, you got this. Just keep being you. You’re not weird.”

Follow the path of the pen. GN