FRESHLY BREWED coffee steaming in your favorite cup patiently waits as you fill a small plate with pats of butter. You slowly pour sorghum syrup over them, then swirl it together until the sweet, amber, ooey-gooey goodness is just right for your hot buttermilk biscuit. You don’t rush it; you savor it. It’s not just something sweet to finish your breakfast; it’s an experience. And for one area family, crafting sorghum molasses is a seventh-generation tradition.

Every year, the English family fires up the stove under the cooker and connects electricity to the presser mill originally powered by mules. Timing is everything, from the perfect weather (a cloudy day is not your friend) to skimming and pouring at the right time. They’ve never missed a year.

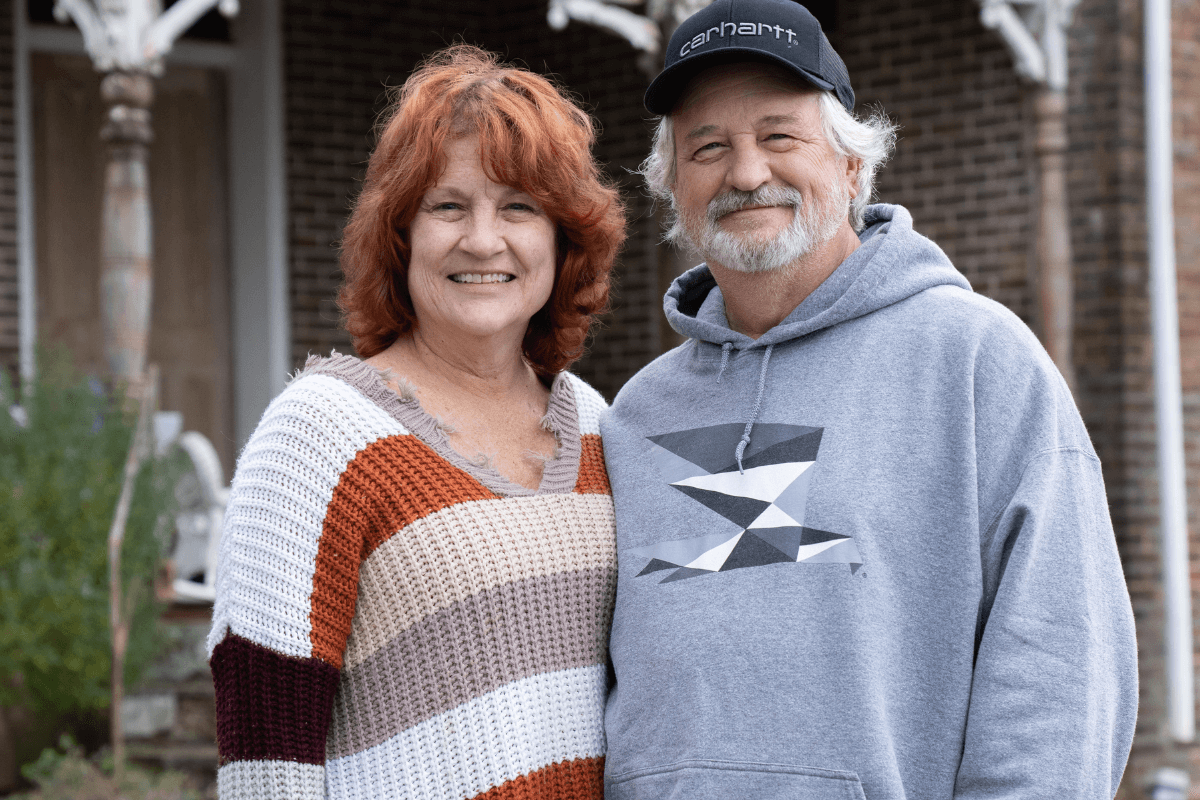

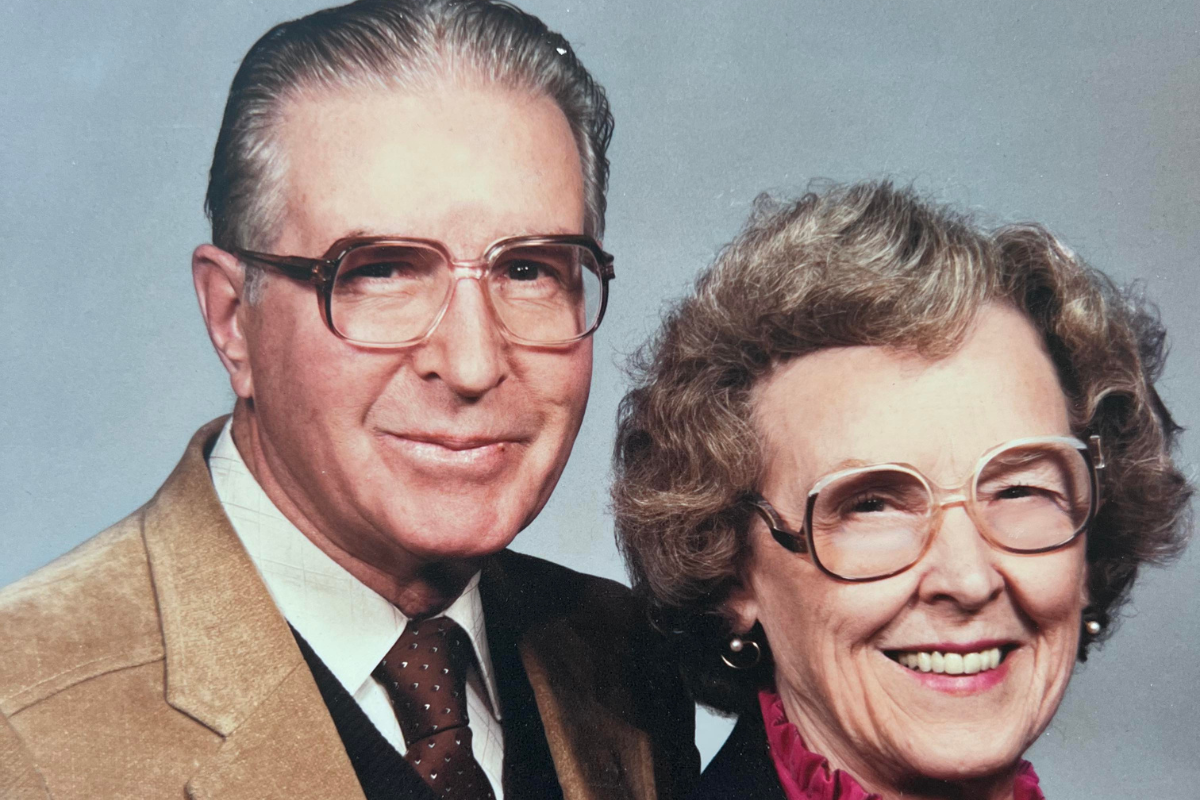

For one day in late fall, the past is alive, and life slows down. On the Century Family Farm deeded to William Bryson English and his wife, Sarah Jane Kidd English, upon their marriage in 1867, William became the family’s first-generation molasses maker. He passed the sweet tradition to his youngest son, Charlie Ross English, who taught his son, James Cullum English. The skill was passed on from him to his son, Jimmy Thurston English.

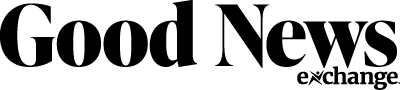

Jimmy Thurston “Molasses Man” English didn’t want the tradition to fade like sepia photographs in albums of memories. Like those before him, Molasses Man understood the value of the relationships and bonds formed when a family works together, catching the juice mashed from the sorghum cane and hovering above the stove, faces semi-obscured by the wisps of the cooker’s smoke. It’s a labor of love, and he wanted his son, Buddy, to preserve it.

But the work begins in spring when Buddy’s son, Jedidiah, plants three or four acres in a tall, broad-leaf plant that resembles corn and isn’t to be confused with the sugar cane used in traditional molasses. Sorghum loves our Southern climate’s hot and dry conditions, and farmers loved the cheaper, more accessible sweetener when it was first introduced.

Buddy said, “Seed is readily available in several different places. You can keep the seed back and replant it, and co-op gets the old-time sorghum that Granddaddy used to plant.”

Like the seeds of tradition first planted on the property over 150 years ago, good things take time. Early spring rains and summer’s sun coerce the cane out of the soil, and when the days grow shorter and the nights cooler, it’s time to make molasses.

The family pairs off as grinders and cookers. Grinders cut the cane fresh from the field, and its pressed juice is heated in the cooker.

“A lot of people kept the circulating pan, but you can’t get it as thick as we do with the stationary pan,” Buddy said. “You have to get the skimmings off, and it’s thicker when it comes off.”

This isn’t the time when a little goes a long way. It takes 10 gallons of juice to produce one gallon of molasses.

Buddy said, “We make 30 to 40 gallons a year. We don’t make a lot; we just do it to keep the tradition alive. The tradition is that the granddaddy taught the grandson how to cook in my generation. My granddaddy was doing the mule while the other men were doing the cookers.”

Today, Jedidiah carries the molasses torch, honoring the wishes of Molasses Man, and passing it down like Jimmy wanted.

Today, Buddy joins Jedidiah at the cooker as Jedidiah continues the tradition with his children, Emree, William Bryson, Charlie Ross, and Jeremiah — two of whom are named after previous generations.

“They’re learning. They’re young, but they’re learning,” Buddy said about the latest generation of molasses makers.

It may be amber-colored, but it’s more like liquid gold. A limited number of jars are available at Fayetteville Lumber, and the English grandchildren sell some directly to those lucky enough to catch them.

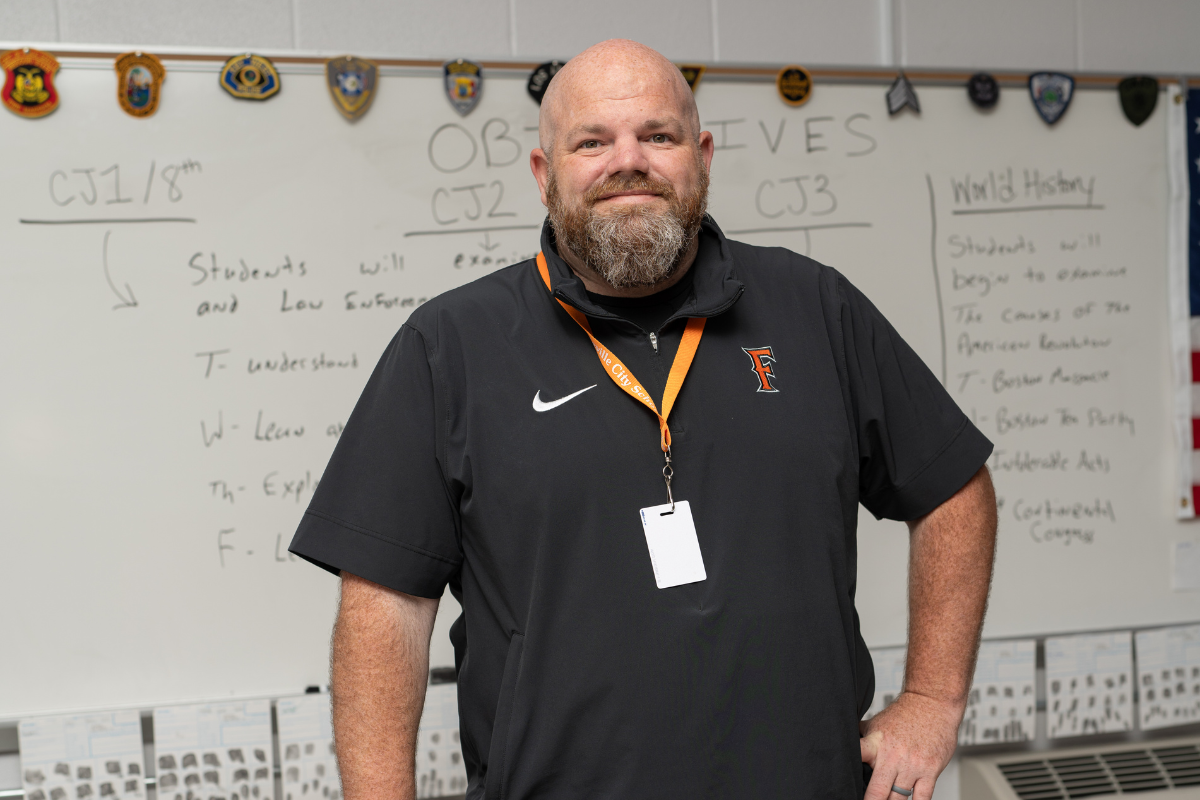

For a time, school buses filled with members of the local Future Farmers of America group gathered to watch the family work. Neighbors who never tire of watching the time-honored process continue to enjoy watching the family work today.

As the embers in the cooker fade and the aroma of sorghum interweaves with the autumn air, you realize the syrup isn’t just a sweetener; it’s a living history book, its pages whispering of resilience, family bonds, and the enduring spirit of tradition.

Seven generations have poured their hearts into this legacy, each year echoing the one before. From Charlie Ross English’s first harvest to Jedidiah’s son looking over his shoulder at the cooker, the flame of tradition has never flickered. Yes, time brought changes — tractors replaced mules, and electricity powers the presser mill — but the core remains unchanged. The patience with the weather, the meticulous skimming, and the shared laughter around the cooker are the timeless ingredients that give the molasses its soul.

In the eager eyes of the next generation, the English family’s sorghum story doesn’t end with the final jar. It waits, simmering like the golden syrup itself, ready to be passed down, savored, and shared, ensuring that the sweet taste of tradition continues to warm hearts and connect generations for years to come. GN