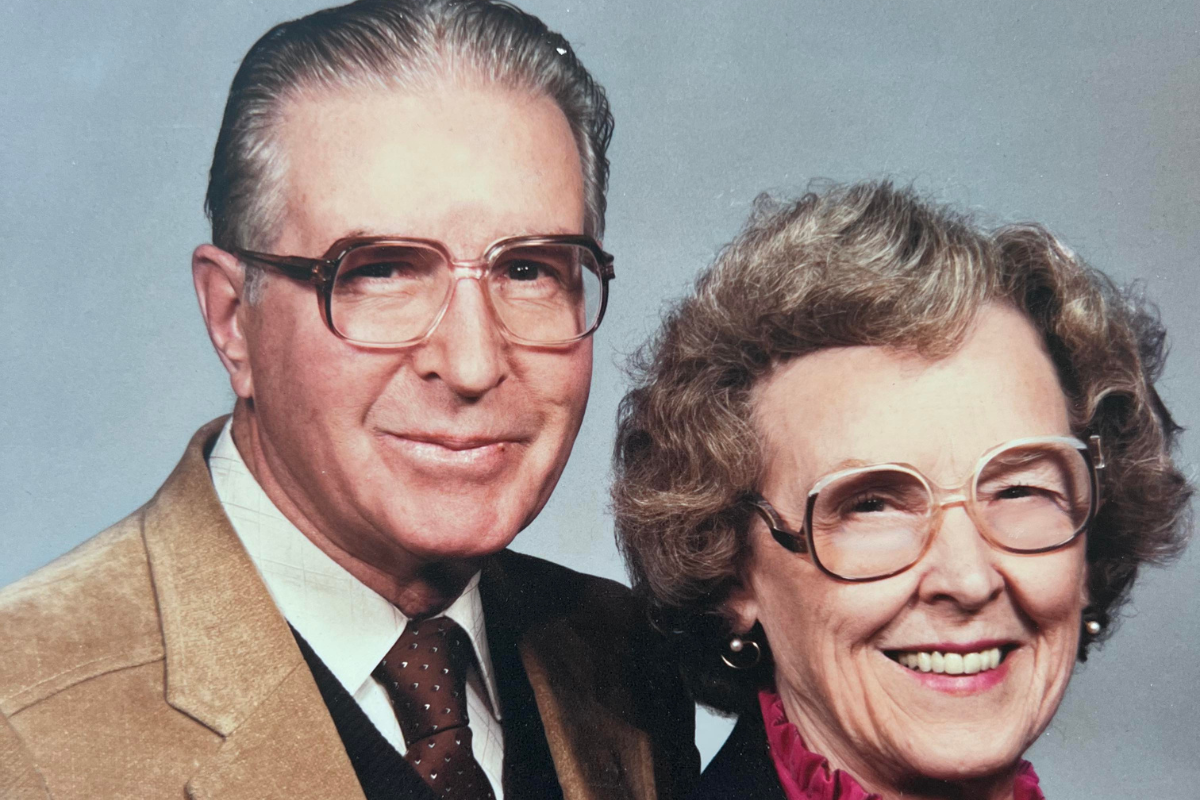

IT’S ONE of our most basic needs, present from birth: the need to belong. To feel seen, heard, understood, and cared for is a critical part of our development at all ages. Karen Gardner saw the people in her community — really, truly saw them and cared for and about them. She spent her life serving and caring for others as if responding to a call audible only to her.

And though she constantly served those outside her home, those inside never felt left out.

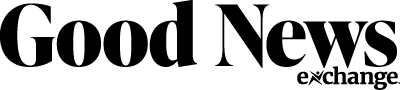

“Mama was more dedicated than anybody I can imagine. She was there until the job was done, no matter what time it was, and you couldn’t have talked her out of it to save your life. My mama belonged to the community. She loved the community, the children of Lincoln County, and Lincoln County just as much as she did us,” said Kim Gardner Baker, Gardner’s daughter.

In the ‘70s, karate kick-started Gardner’s career in the direction of law enforcement.

Baker said, “In 1974, she got her black belt. Back then, that wasn’t something women did. Then, she started teaching karate here in town. She did it for free because she wanted to help kids and get people involved in karate because it was good for your mental state, discipline, and all that. And she wanted to do it for free to help other kids get that experience.”

Gardner spent several years at Amana with a term in the United States Army at Redstone Arsenal sandwiched in between. The single mom’s official service to her country ended when a tour in Korea would be the next assignment. But her service to her community was just beginning.

She signed on as a volunteer officer with the Fayetteville Police Department (FPD) while working at Amana. The many unpaid hours she spent with the FPD clarified her true calling, and in 1988, Gardner took a 50% pay reduction to become a full-time officer. It was a small price to pay, and she moved from patrolman to investigator, where crimes against children, especially, moved her.

During this time, she enrolled in training with her daughter, Baker, for a position as a foster parent. Baker couldn’t complete the course then, but Gardner moved forward, motivated by her caregiver’s heart. Her daughter ultimately became a foster parent, but Gardner beat her to it and went on to adopt two of the children she fostered, Charlie Gardner and Brianna Warren.

“Living in a small town like this, you don’t realize what some kids go through until you get involved with the foster care system, and then you see how blessed you are to have a good family,” Baker said.

But Gardner saw it and spent her life doing something about it.

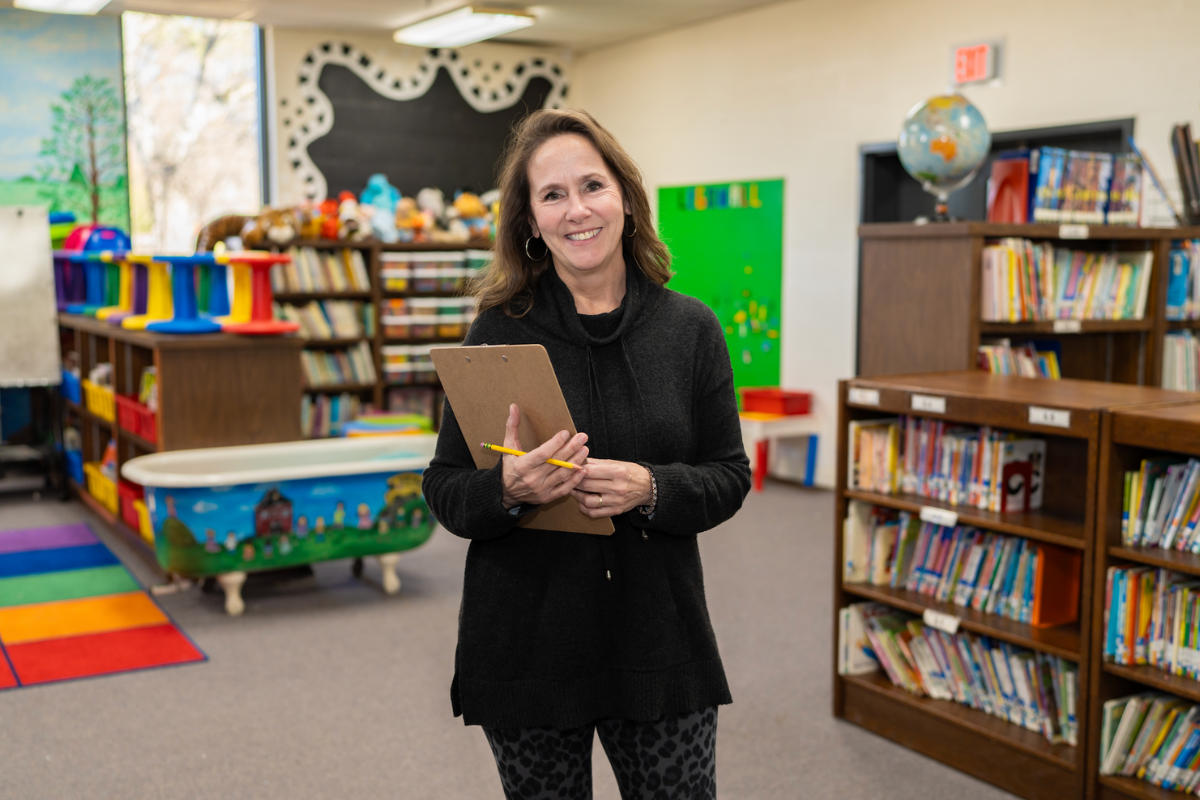

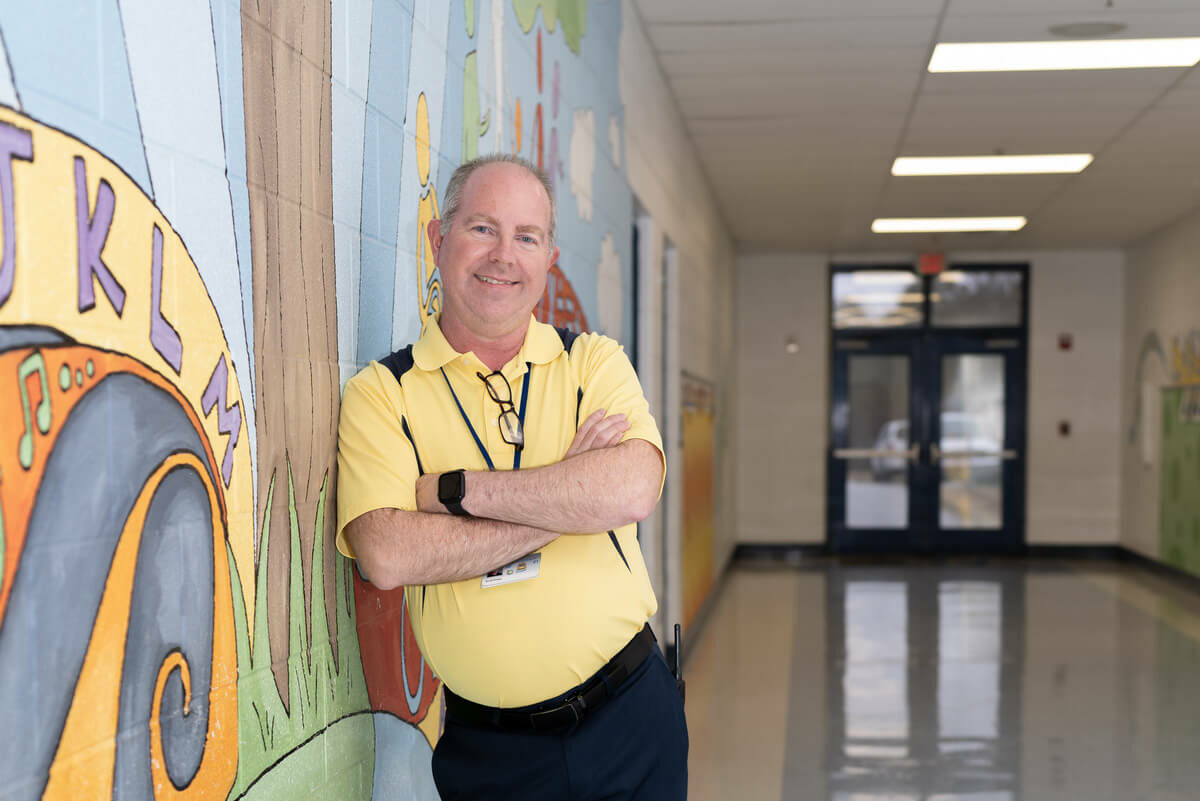

When Lincoln County began its school resource officer (SRO) program, Gardner was among the first to sign up, moving from the FPD to the Lincoln County Sheriff’s Department (LCSD).

“It was perfect,” Baker said. “She loved kids, so it was perfect. She was a patrolman and SRO, mainly at the school. Now, they’ve got SROs in every school, but when Mom was there, she had to do [several] schools. I told him they had to get five or six officers to take my mom’s place.”

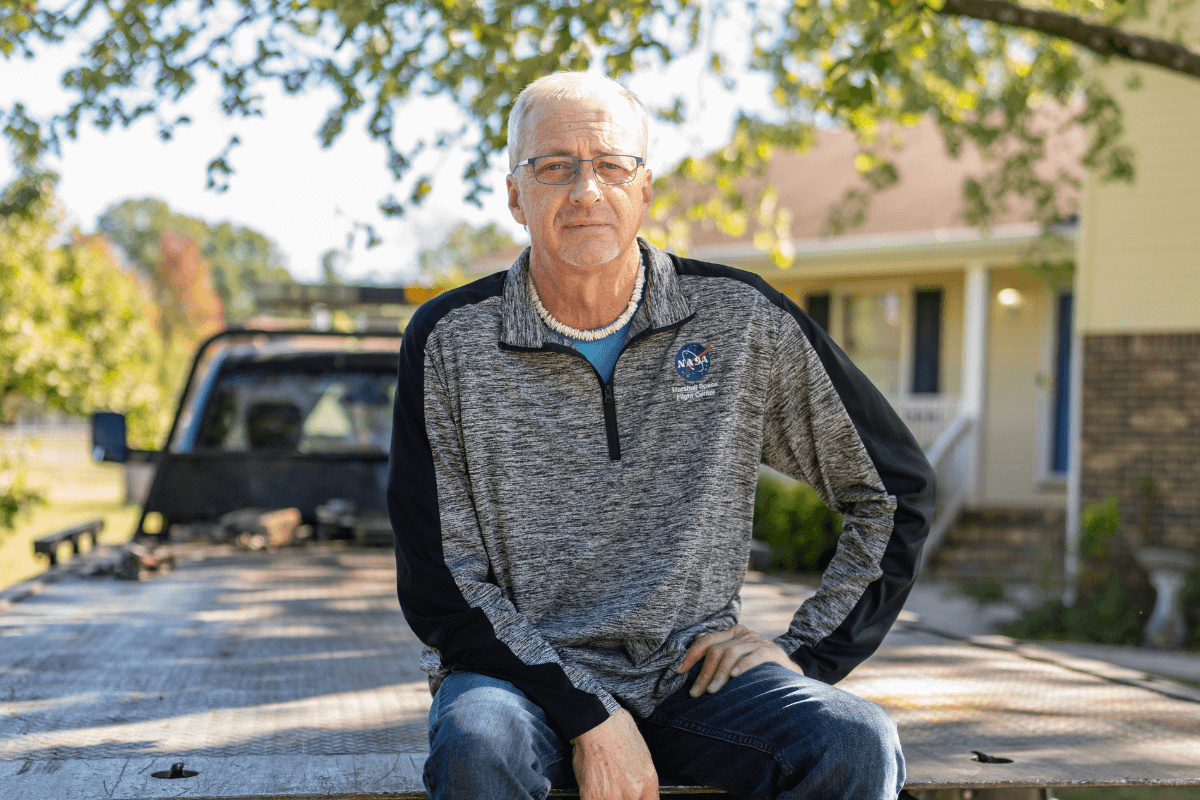

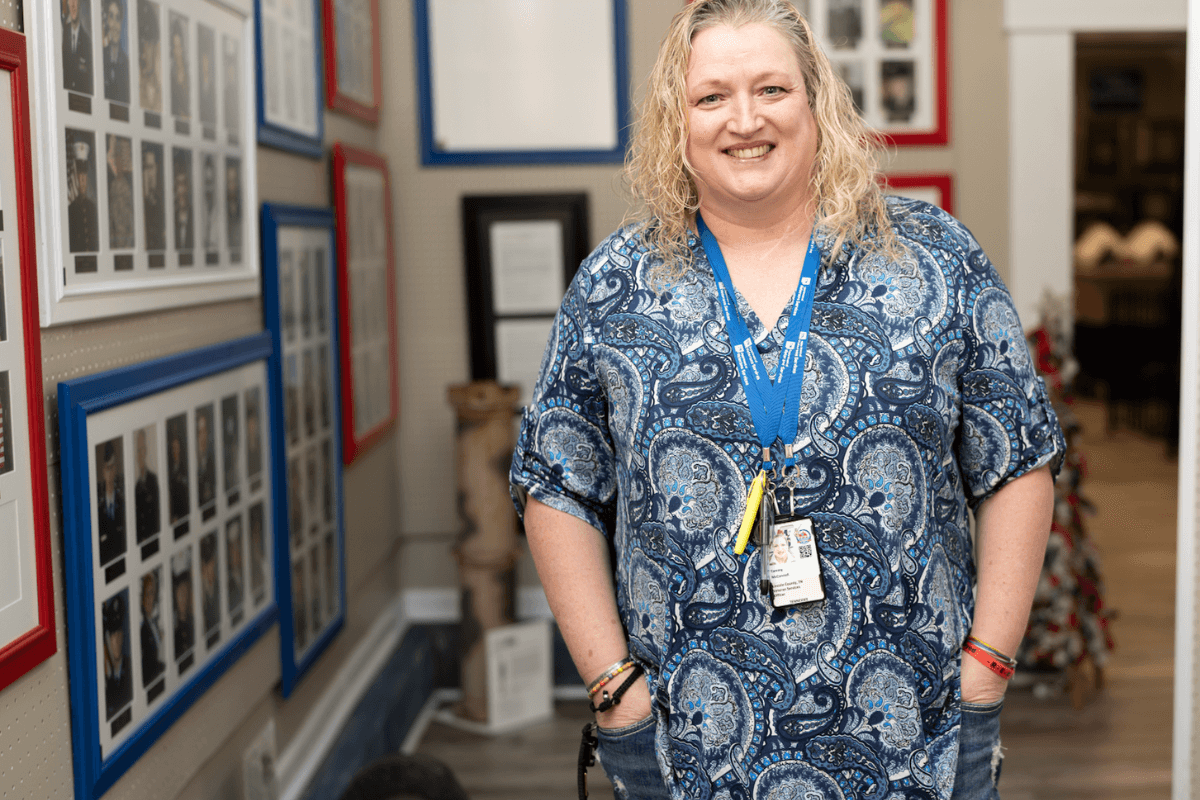

Carman Smith, former director of health and safety at Lincoln County Schools, saw Gardner’s dedication firsthand. Gardner’s passion for her job impacted more than students.

“When I took the job, we didn’t have SROs in every building. We had Karen, and we had Bill Wood. Karen trained me on what being an SRO was supposed to look like. It was, ‘Yes, I’m a police officer, but this is about the kids,’ and not everybody can be an SRO,” Smith said. “She set the standard for me that I used for the rest of my career managing the SROs. She helped build the program from the ground up and was an integral part of getting it in place and setting the standards. She set the bar on what it’s supposed to look like.”

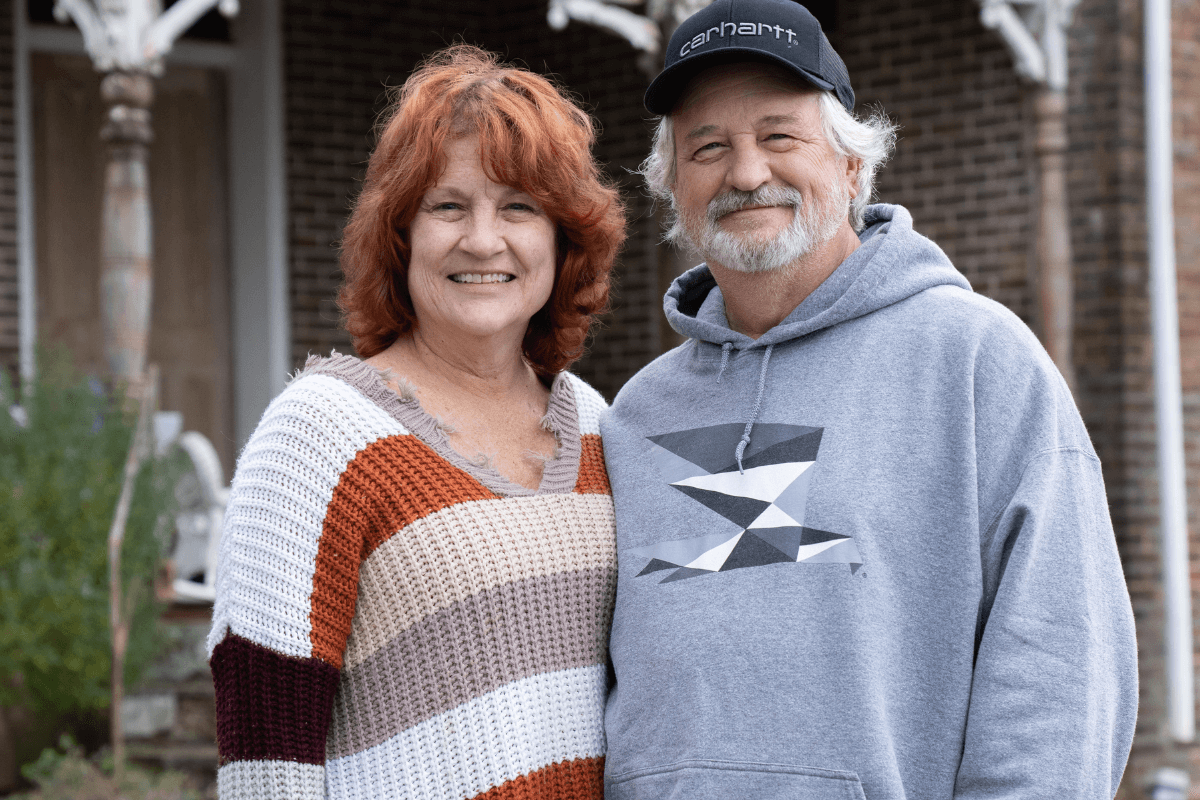

Lieutenant Tony Metcalf, who manages the SROs today, took Gardner’s SRO position upon her retirement and spent many years before that on the force with her.

“Karen Gardner was the salt of the Earth. She took care of more people than most anybody I know. Karen’s been a mama to more kids, even those that had parents. She was our mama. She took care of me when I started in law enforcement, and she was good to me. But she was always looking out for those kids,” said Metcalf.

And she couldn’t stop looking out for those kids when she retired as an SRO. She found her way, sometimes literally, back into the schools as a substitute teacher. Even with vision problems and a walker, she was there for the kids.

When she passed away in Maury County Hospital last year, her fellow officers escorted her home.

“When Mother passed away, the police officer on duty at the hospital stood watch. She had been away from law enforcement since about 2017, but Sandy Metcalf with the LCSD sent two deputies to the hospital, and they escorted us and the hearse back to Fayetteville. The Maury County deputies and city officers had all the [traffic] lights stopped for us. Then, a Lincoln County deputy kept 24-hour guard at the funeral home,” Baker said.

How fitting that so many stood watch as the one that stood watch over the children and members of the Lincoln County community came home one last time.

Her legacy lives on, though, in those she trained and influenced: her friends, family, and the students whose paths were redirected by her intervening tough love.

She was our mama. GN