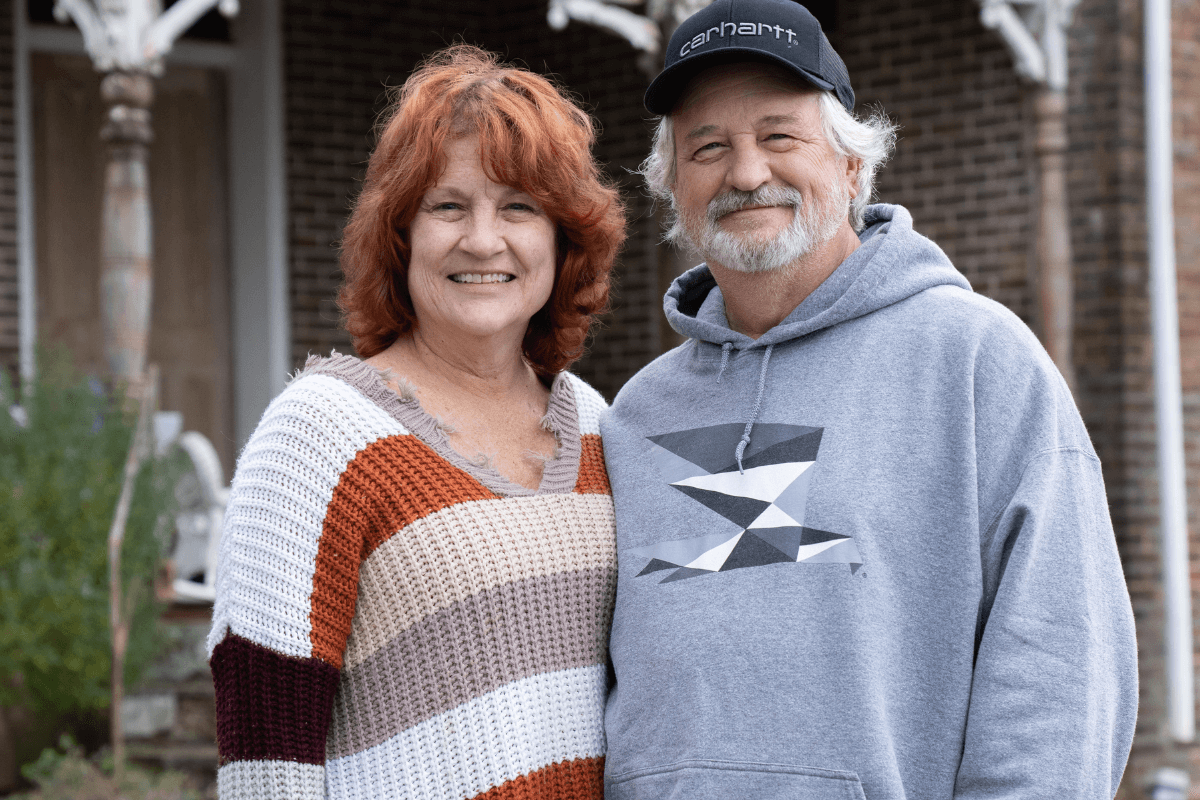

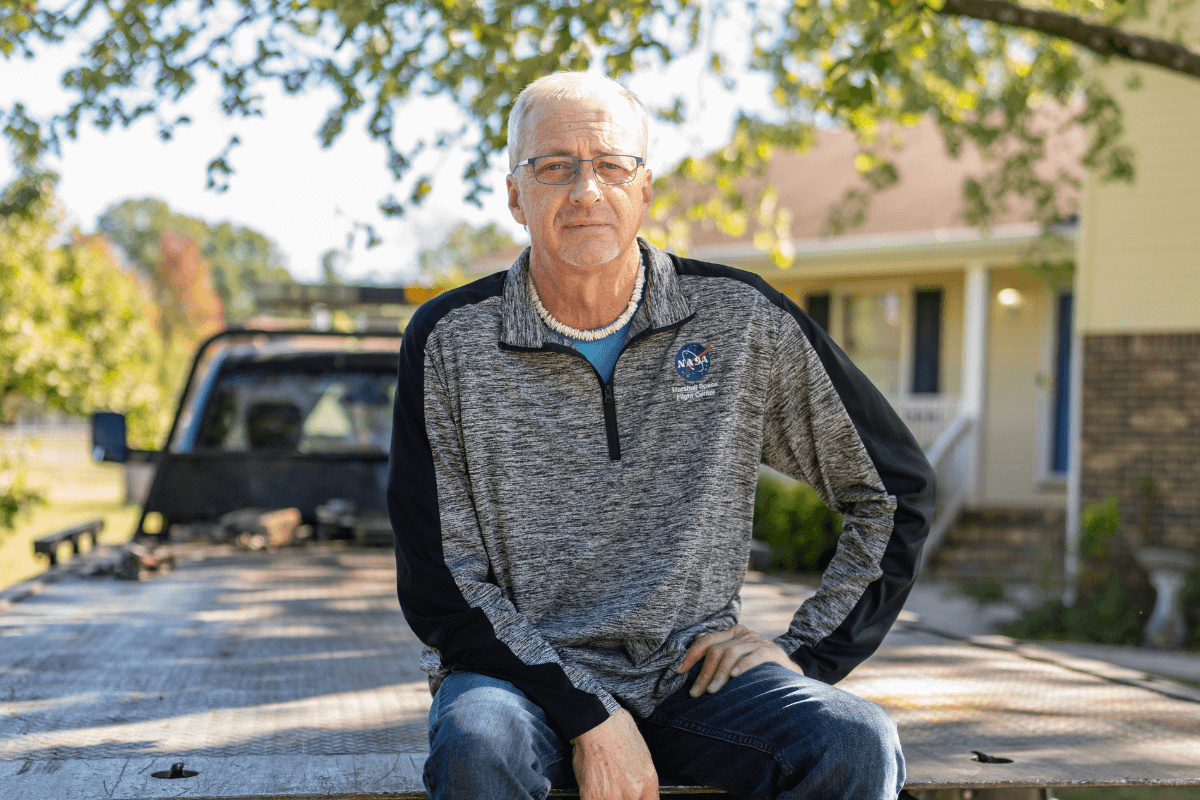

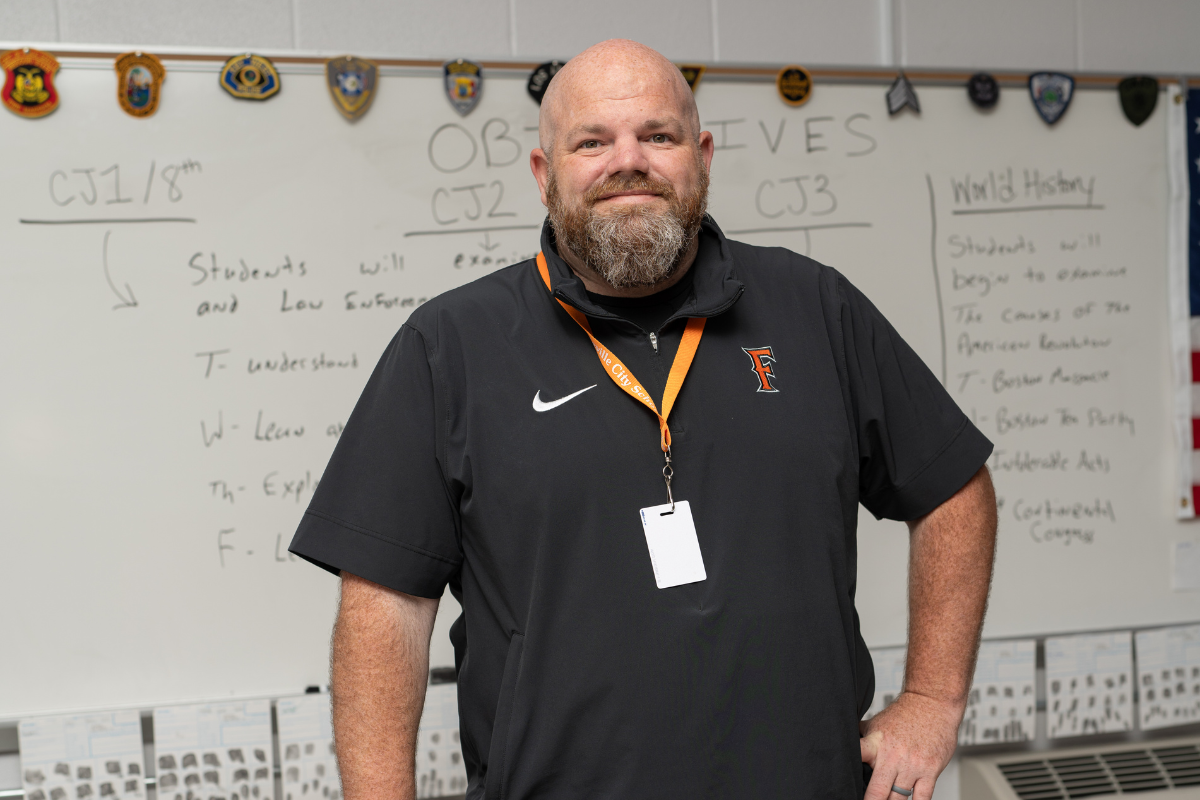

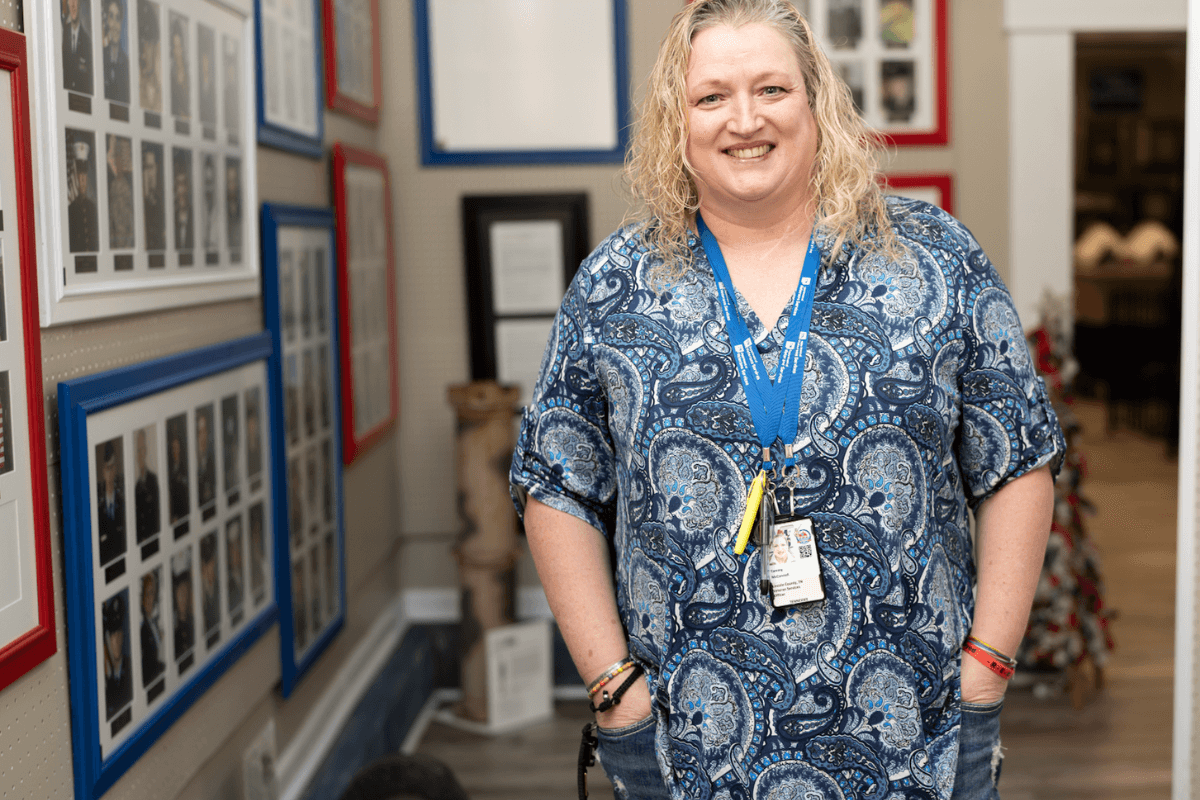

FOR OVER two decades, former Sheriff Jimmy Mullins dedicated his life to law enforcement, ensuring justice and safety for the Lincoln County community. From heartfelt rescues to challenging situations faced head-on, he brought quiet dignity to every call.

A career in law enforcement was not a choice he made lightly; it was a calling and a desire to bring a different approach to how people were treated and respected in his line of work. Mullins witnessed the actions of some police officers in earlier years and their treatment of people as they responded to calls, leaving a deep impression on him. He knew there had to be a better way.

“It was a childhood dream; I thought, ‘I’d like to be in law enforcement.’ Over the years, I’d seen things police officers did, [and] the way they acted and mistreated people back in the ‘70s. Some of them wanted to be bullies, but I knew it could be done differently, and people could be treated better,” he said.

The first step to fulfilling his childhood dream was becoming a member of the sheriff’s volunteer program. When a new sheriff was elected in 1998, Mullins struck up a conversation with him at church and soon after received a call from the sheriff for a fitting for a deputy uniform.

“A lot of things can happen, and it depends on how a person looks at it; just one or two decisions can change where you are today,” said Mullins. “If we hadn’t gone to church where the first sheriff I worked for attended, and if I hadn’t talked to him, I might never have even got in.”

Although he sometimes left law enforcement for civilian work, Mullins always returned to the sheriff’s office. The desire to make a positive difference stayed with him as he rose through the ranks, becoming a chief deputy, sergeant, and finally, the elected sheriff of Lincoln County.

What kept drawing him back?

“Well, I enjoyed it. When someone’s stolen a farmer’s cows, and you can call him to come get them, or if someone had a chainsaw stolen and you recovered it and solved some other crimes at the same time, it’s satisfying. But it’s not satisfying when you can’t solve a crime or help somebody,” said Mullins.

Helping the people of Lincoln County and restoring to them what others tried to take away was important to him. Although many more generations are now here than when he was in office, he knew the people he served, and they knew him.

“My granddaddy was bad to ask people who their mama and daddy were, and he knew a lot of people that way,” he said. “I’m bad about that, too, and I know a lot of the people that live here. I hated when we moved to Michigan [as a child] because I wanted to be down here on Grandpa’s farm. There’s a bunch of good people here in Lincoln County, and I used to know a large section of the county.”

Throughout his career, Mullins faced challenges that tested his resolve, but he never wavered in his commitment to serve the community. On one of his earliest calls as sheriff, a Giles County father abducted his child. Finding the man and taking him and the child into custody without incident or force reaffirmed his calling.

“He was in a field close to the river at a gravel pit. I got out of the car and started walking, and I spotted him just standing there with the baby in his arms, gazing out into the field. I eased up on him as close as I could without spooking him, and I told him, ‘Lay that baby down and move away from him.’ And he did. He put the baby down, and I radioed the ambulance and some more help and eased on toward him. I secured him, and he didn’t give me any trouble. I picked the baby up and had the daddy walk ahead of me toward the car [where more help arrived].”

It was rewarding work but not easy work.

He said, “We had to put in a lot of hard work, from 10 to 12 hours a day, six days a week. Of course, you’re on call all the time, and it didn’t pay a whole lot, but it was a regular paycheck,” he said.

It was inevitable that some calls involved traumatic incidents, but Mullins refueled and refocused by finding a moment to sit in silence. He had to keep moving forward.

“Most things are what you make of them,” he said. “I believe that most officers are out there to help. I was there for 22 years and some odd months. I never used a nightstick or blackjack and never shot anybody. I slapped two people. One hit me with his fist, and I slapped him. I didn’t let my people abuse anybody when I was chief deputy or sheriff, and they knew we didn’t put up with that. I guess I was lucky, though. ”

Mullins believes his story isn’t unique. Still, his non-violent career shines even brighter when today’s national news replays endless footage of violence in city streets, including officers using excessive force. Law and order standing on the shoulders of solid character and higher standards provide security to everyone in the community.

Childhood dreams and a desire to see positive change are more important today than ever, and the bonds of Lincoln County residents make us stronger together. Communities with that kind of support and stories like Mullins’ may not be unique, but they’re priceless. GN