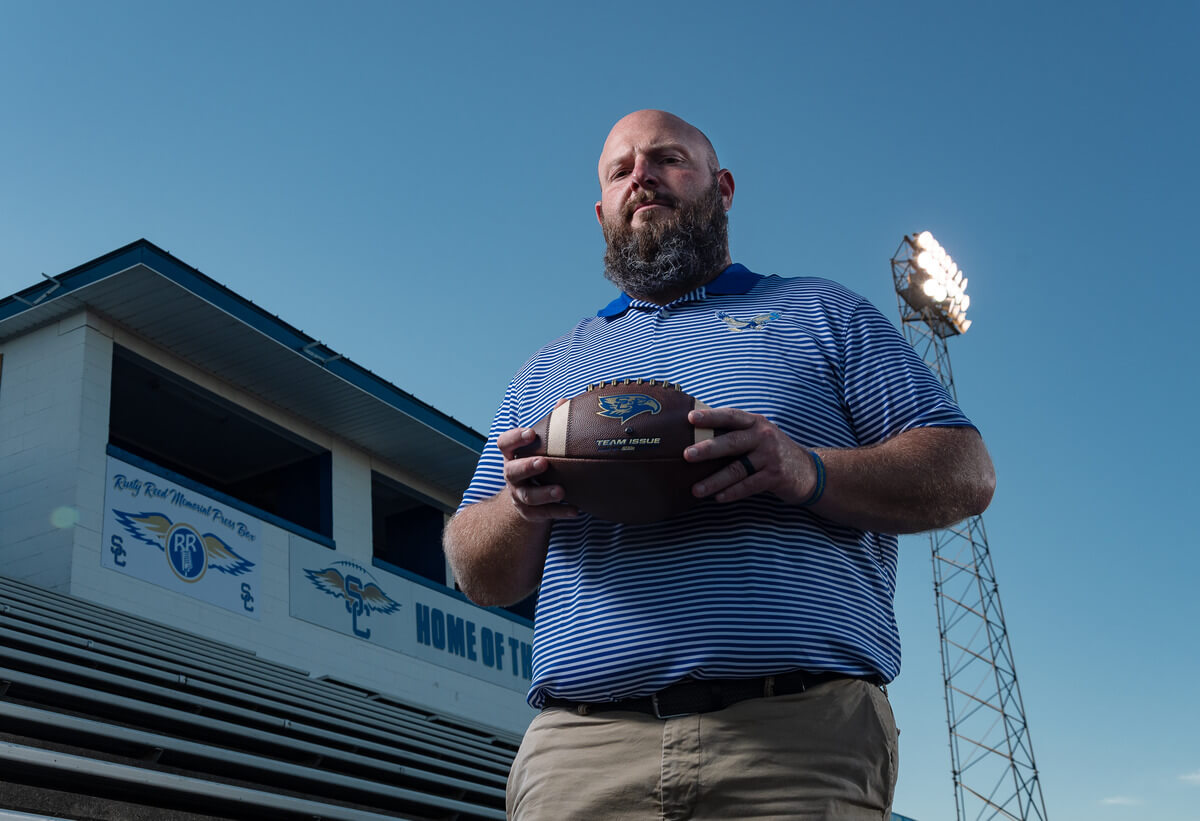

WE HAVE no problem imagining heroes as someone rushing into dangerous, life-threatening situations and saving lives and property. Our heroes come in many shapes and sizes, wearing different uniforms or civilian clothing, and quietly weave in and out of the fabric of our lives. Other heroes, like Lt. Chris Cook of the Bedford County Correctional Facility (BCCF), offer tools that change and sometimes save lives.

In each inmate, Cook sees more — more than their past and more for their future. He sees root causes more than rap sheets; he sees pain and trauma that hold hope hostage. He sees potential and possibilities, and his greatest hope is for us to see the same.

Cook said, “There’s always been this idea that people in jail are bad, and I don’t disagree with that. But when you remove the addiction part, you can get through to the person, and the person minus the addiction is not necessarily evil. And that’s what we’re starting to see. If we can deal with the addiction, we can eliminate the other crimes associated with it.”

Addiction and the crimes related to it that resulted in incarceration were different in Cook’s earliest days as a corrections officer.

“Before, people drank and smoked marijuana because, for many, it was their only option. Then, in the 90s, you saw a big outbreak of doctors prescribing opioids. That’s kind of where it all started,” said Cook. “Opioid addiction is expensive. We’ve always tried to reduce the supply, but you can’t because there’s still a demand.”

Cook took a break from corrections work and obtained a psychology degree before returning to the jail in 2014. The jail population had significantly increased since he left, and the charges were more serious. The more he talked with inmates, the more precise the root of the problem became. Most suffered some kind of trauma early in life, and addiction numbs the pain.

He said, “Over and over, all they know is they need what they need, and they’ll do whatever they have to do [to get it]. I’m not making light of what they’ve done. I’m not saying that it’s not wrong, but it is possible to reform them. If we can deal with the addiction, all the other stuff goes away.”

Dealing with the addiction is a process.

“When I came back to the jail, I didn’t have any specific training with addiction, but I had quite a bit of knowledge about motivation and changing people’s behavior,” Cook said. “That’s the main reason I stayed; I realized these tools are what you need to help people deal with addiction.”

And one person at a time, they’re dealing with addiction at BCCF.

Cook offers Moral Reconation Therapy (MRT) to inmates willing to do the hard work of looking deep inside and out, examining the source of their pain or trauma, and owning the hurt they’ve caused for themselves and others. It equips them with tools that empower them to make better choices in the future, and they learn accountability and responsibility.

Offered to both male and female inmates, approximately 60 of them have graduated from the program. But that’s not the true measure of success.

“We don’t deal in percentages. We’re talking about human beings, so every person we help is one less person [responding out of addictive behavior],” said Cook.

And for every person helped, more than one is impacted by the change.

“You can look at the study. There’s a high probability that if I’m incarcerated, my kids will be or have been incarcerated. And if my kids have been incarcerated, you can almost guarantee my grandkids will be,” he said. “So for every single person we rehabilitate, we’re helping their kids and their grandkids, and we’re changing the future of people who aren’t even dealing with addiction.”

That’s support from the inside. How can we help as a community?

Support is the key to their success. Once released, they need to feel the support of their people, their families, and their community. The second step may be as hard as the first and is critical because a lack of support might lead to a relapse. An outpouring of support, however, might be the bridge to complete recovery.

“In our program, we teach people to take responsibility for their lives. We teach them to be honest and to follow rules — all the things we want to teach our kids when they’re growing up so they come out of jail holding themselves accountable. They want to be trustworthy,” said Cook.

And trust takes time and opportunity to build. It’s not easy for either side, but it is life-changing for both.

He said, “People change. People want to change, but society still sees them as an addict; they still see them as a criminal. And I’m not saying we should take care of every single person who gets out of jail, but we should give them a job, hold them accountable for what they did, and allow them to show you the change.”

Even a relapse following the program is not a failure.

“I think our program is successful because the vast majority of the people who’ve gone through it are out there working and living their lives,” Cook said. “But on the other hand, even the few who have relapsed have picked themselves up and gone to rehab or reached out and asked for help. Either way you look at it, it’s absolutely successful. I just look at success in a different way than most people.”

We can all work together to change lives one person at a time. We can be a community of heroes! GN