GROWTH IS stunted in the shadows. A healthy balance of sun and shade, light and dark, warmth and cool all produce the best in life. While Brooke Smith Sanders is her father’s daughter, walking side by side with him and not in his shadow was fertile ground for producing a farmer.

Farmers in our rural communities are still made up mostly of men, but Sanders’ father, saw fertile soil for his future farmer. His approach to planting seeds for a third-generation farmer was perfect, and the harvest may yield even more generations of farmers.

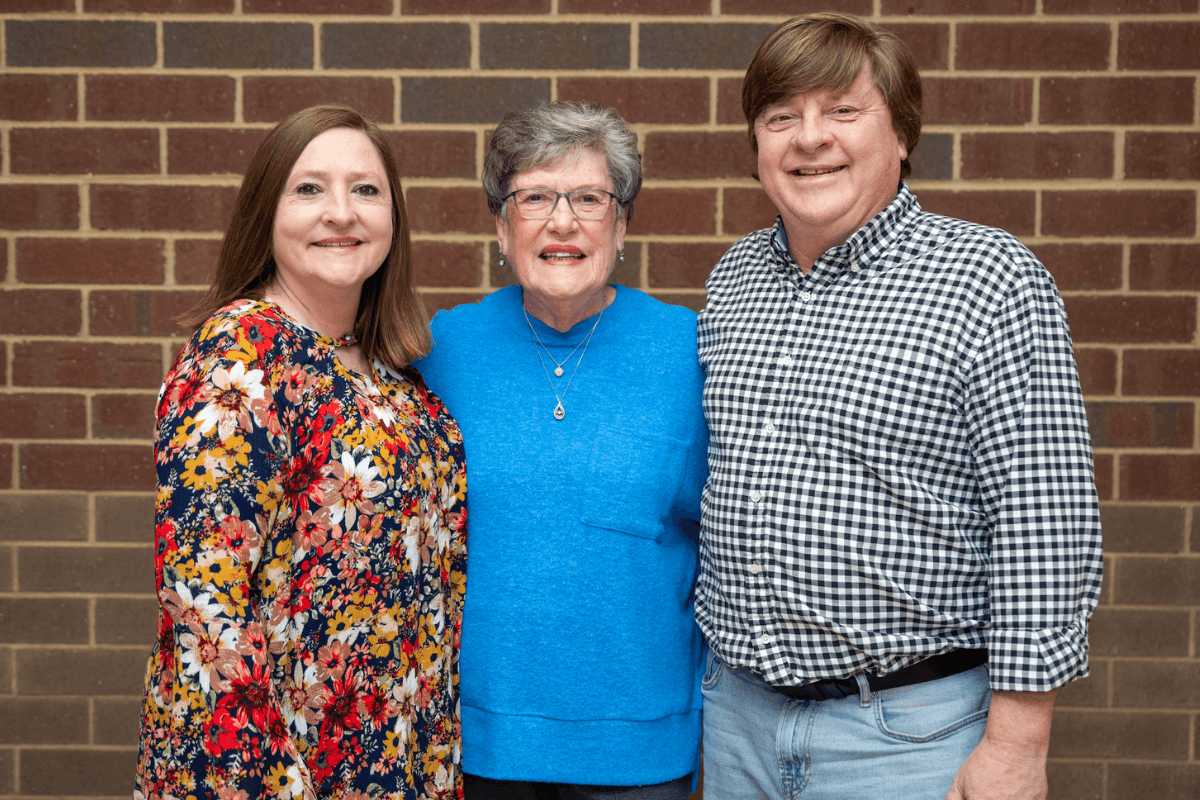

Sanders said, “He was very hands-on. Even when I was young, I would come to him and say I [had] a problem, and he would say, ‘What do you think it is?’ Or, he always led with questions. He would never say, this is what you need to do. We worked together every day, but he and my mama were adamant that I needed to know how to fix things and figure things out because one day, they wouldn’t be here. And that was hard and aggravating, but it was the biggest asset and the best thing they ever did for me.”

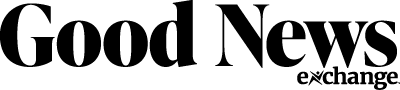

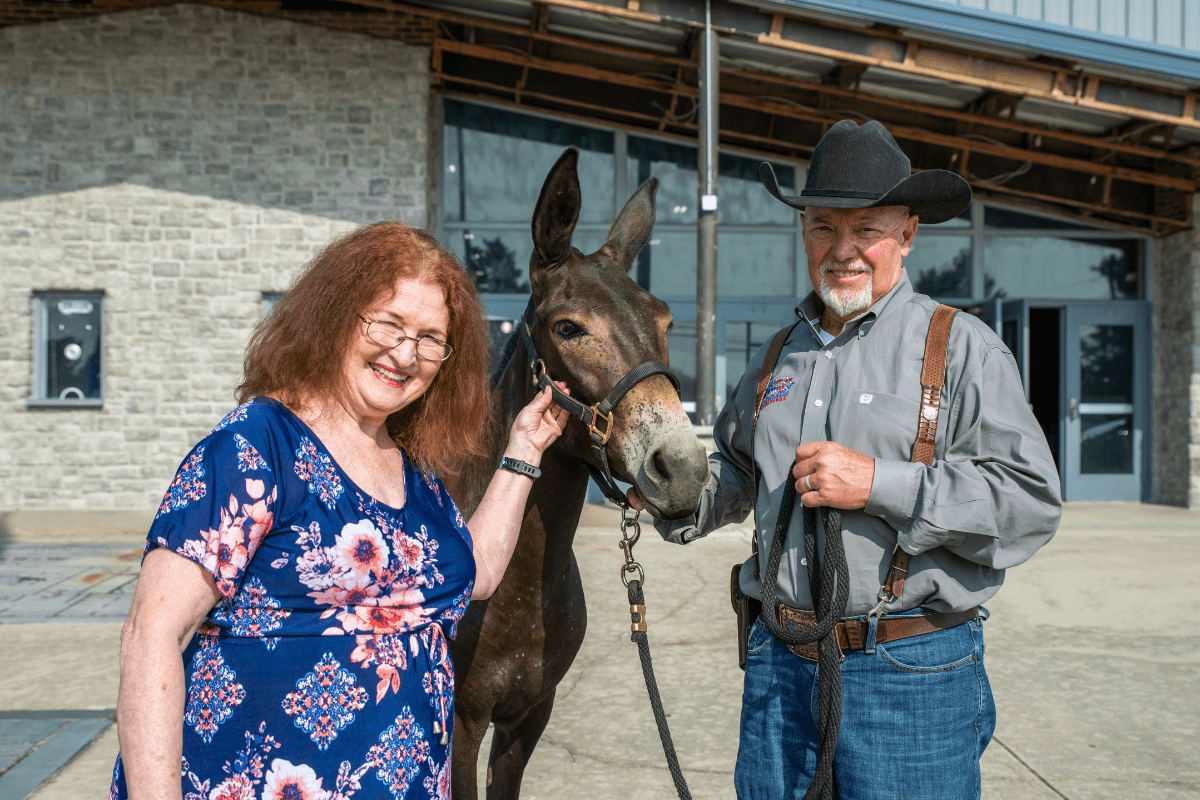

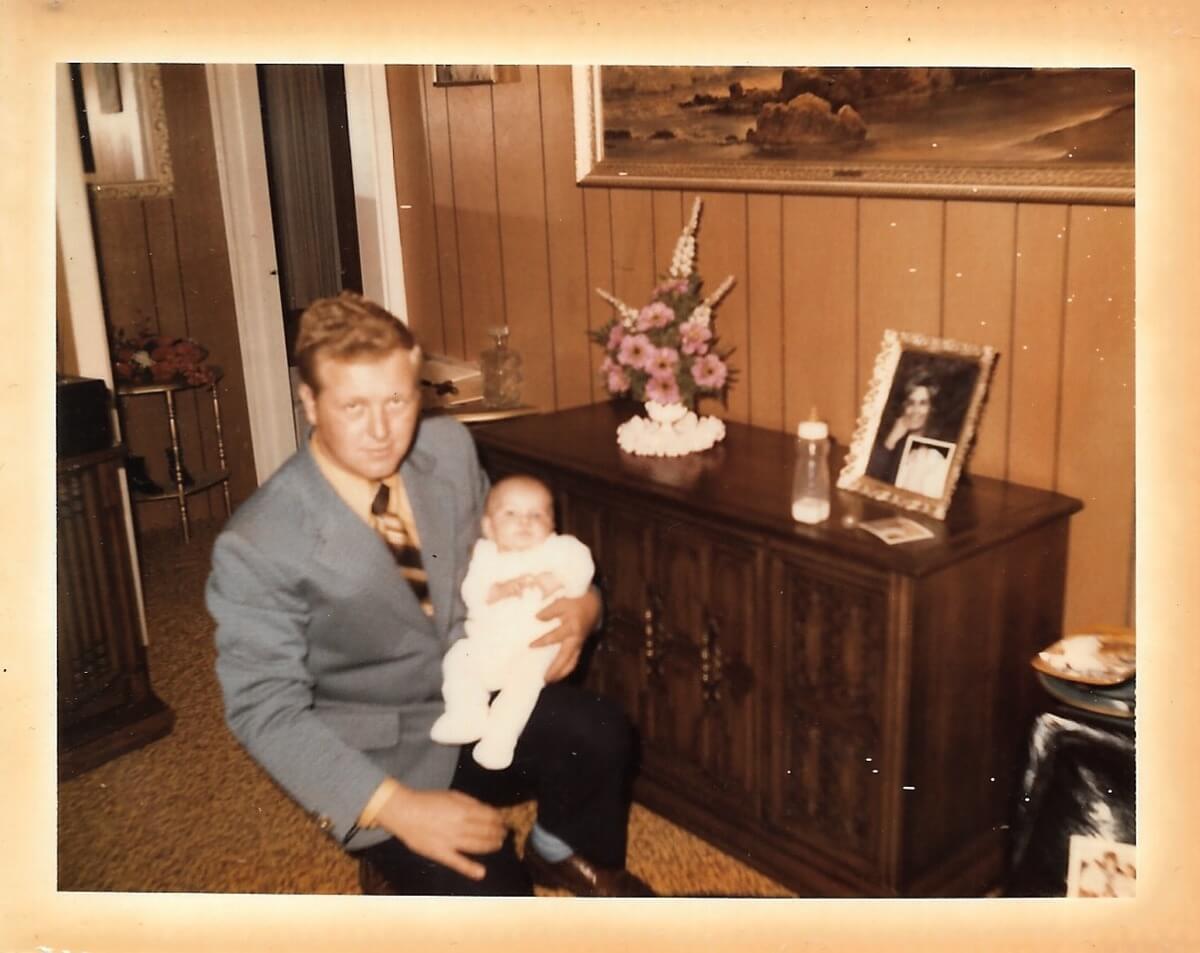

Sanders’ family has a rich history in farming, dating back to the 1960s when her grandparents, and her parents, Jimmy and Charlene Smith, began acquiring and merging smaller farms. Growing row crops and tending to beef and dairy cows were integral parts of their lives.

“My favorite thing to tell people is my daddy made me go to college — he said that was my backup plan,” said Sanders. “I got a degree in agribusiness. You had to take a milk science class to get that degree, and you had to come milk cows. I told the professor, ‘I’m not coming up here to milk cows; I do that at home.’ And my professor said that’s a true reaction of somebody that has milk cows, so I’m going to let you skip that part.’”

The family ceased their milk cow operations during her sophomore year of college and later added hair sheep. Add annual hay crops to the mixture, and you have a picture of Sanders’ life.

“It’s a good life; I love it. My daddy died in January 2020, and there’s been a lot of adjustments since then, but I still love it as much as I used to. And I’m glad I get to do it. I hope my kids want to do it one day,” said Sanders.

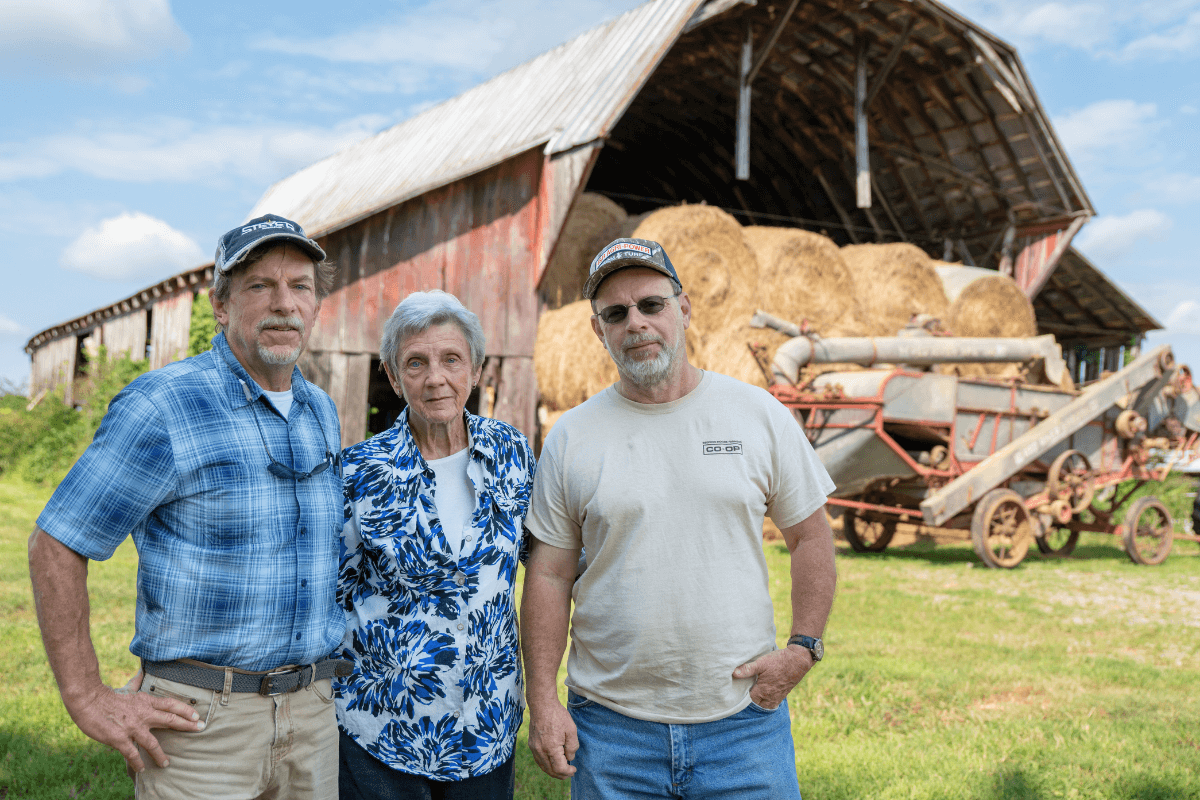

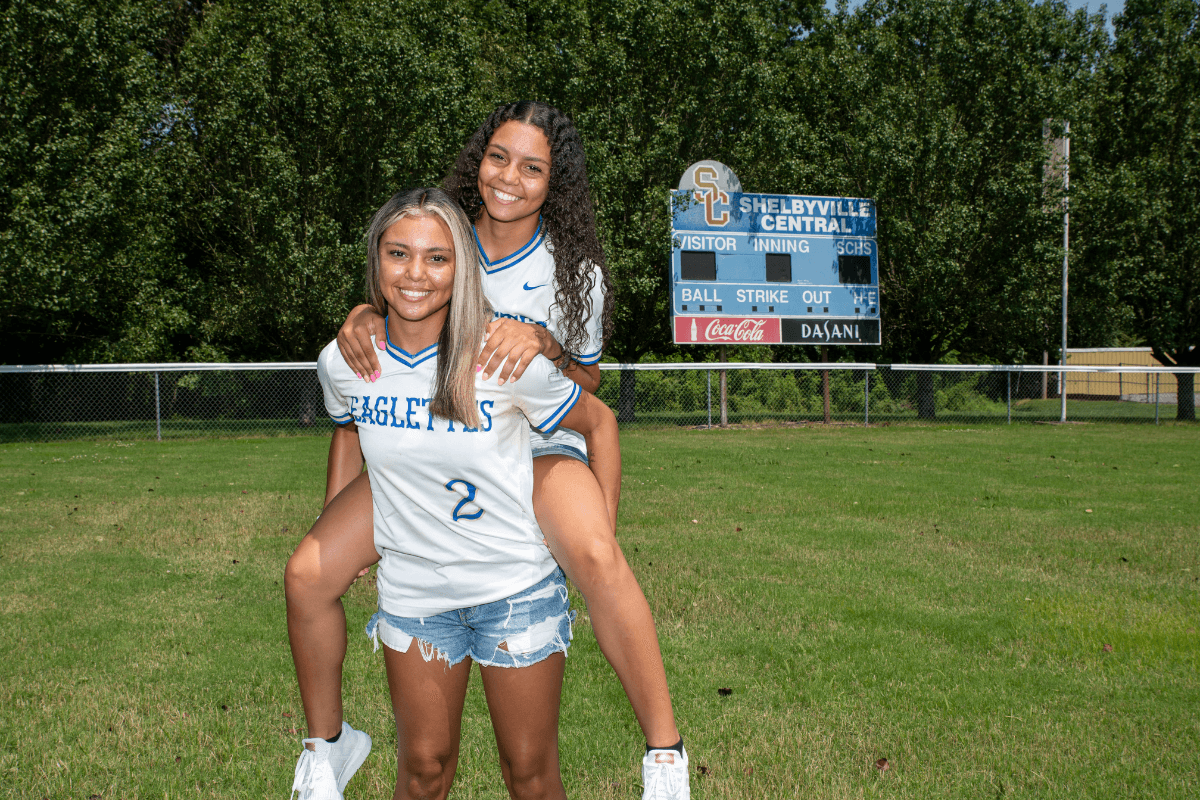

She hopes but doesn’t pressure her twins in the direction of a life of farming. Like her daddy, she shares all of life on the farm with them and will let them decide when the time comes.

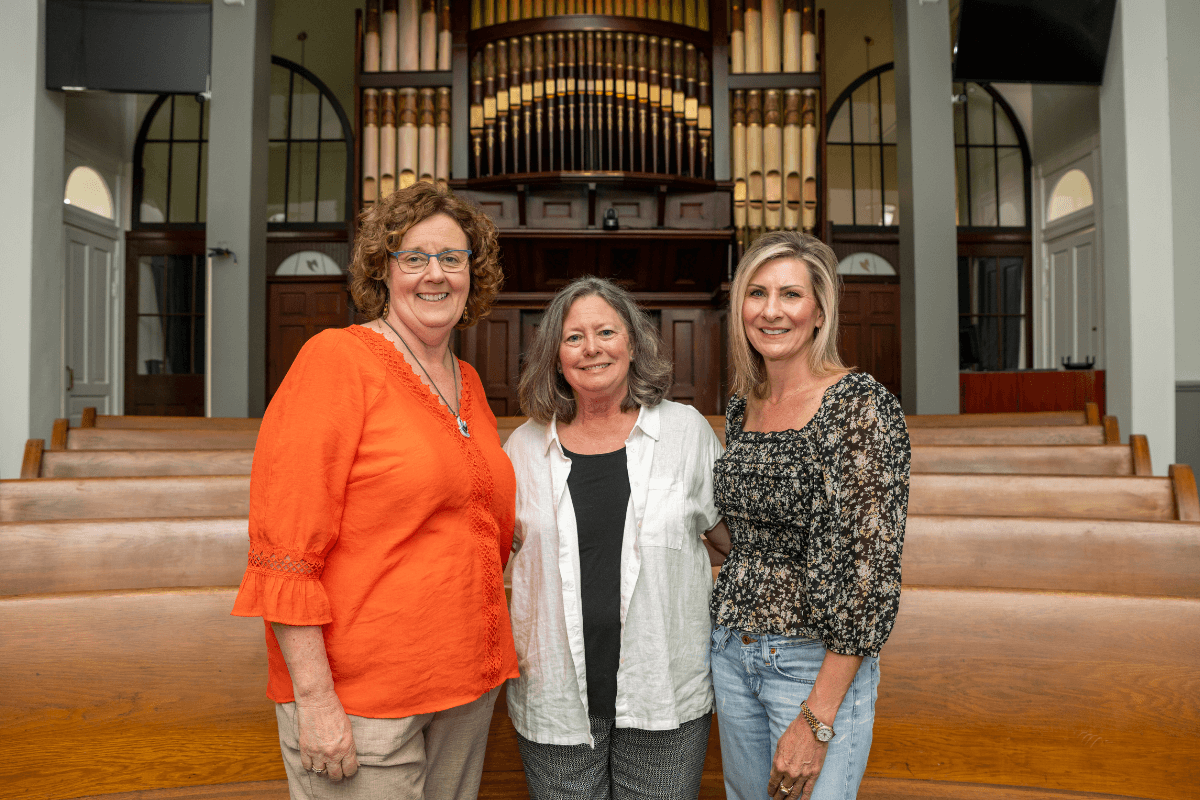

“Growing up, when you farm, you don’t get to go on vacations, and you don’t get to do a lot of things, but my parents always wanted me to have the best of both worlds,” said Sanders. “So, there were times that Mama would take me, my aunt, and my cousin, and we would go on trips and vacations together. My daddy never got to go. As I got older and my responsibilities increased, I could understand that.”

The decision to follow in her parents’ farming footsteps was not forced upon her. Her mother had been adamant about her not pursuing farming due to the demanding nature of the profession. But, her appreciation for the role of farmers in sustaining life and a desire to honor her family’s legacy was as natural as breathing. She cares deeply and personally for their livestock and acknowledges that farmers are often misunderstood and underappreciated.

“I think the common theory is that farmers don’t care about their animals. I really wish people understood that we do,” Sanders said. “We put our entire life into these animals, and just because they’re a food product doesn’t mean they’re mistreated. There are a lot of struggles in farming, and I wish people understood that. Farmers are dehumanized sometimes. We’re all trying to hang on as long as we can, and I think that gets lost in translation.”

What’s not lost in translation is her commitment to and heart for agriculture instilled by her father’s love and example and her mother’s support. Her passion for farming and family runs deep, yielding a harvest of life-sustaining food for others and a model and legacy for her children and future generations.

That’s the circle of life. GN