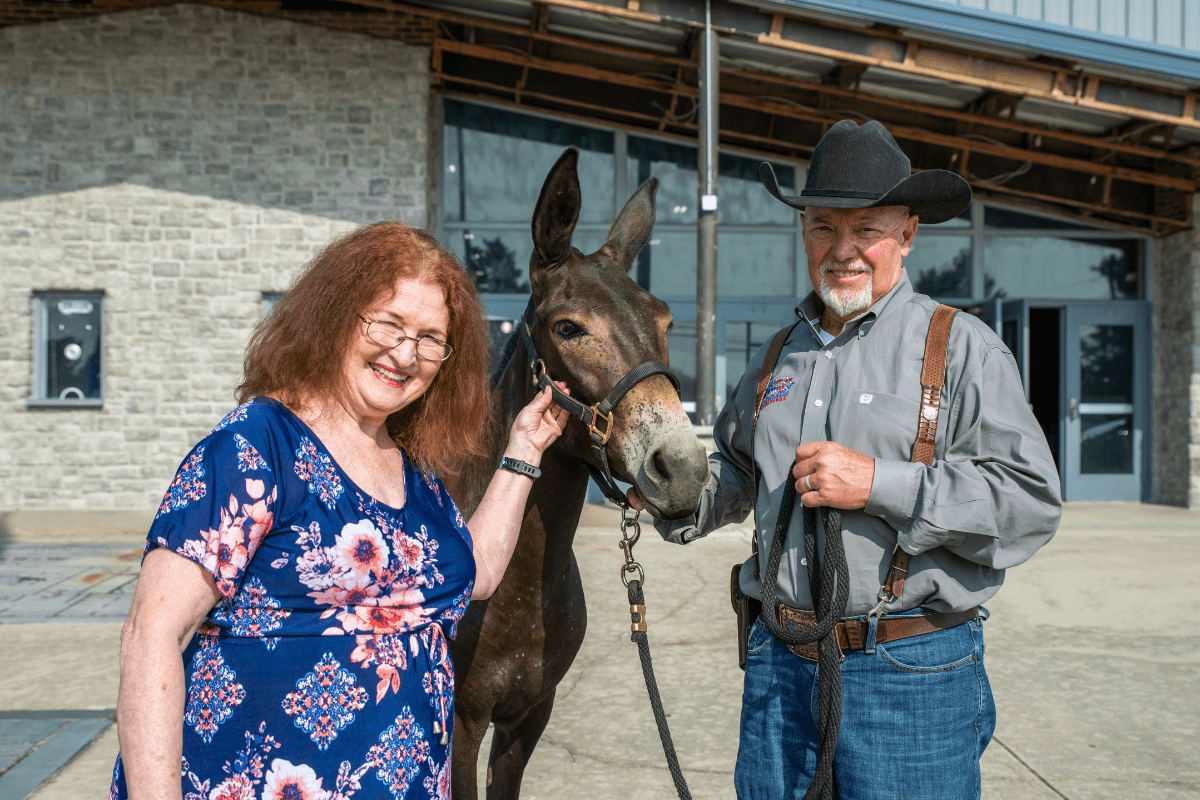

SOME GENERATIONS grew up racing to answer the phone, but not everyone’s phone would ring a solid, uninterrupted ring until you lifted the receiver. That call sounded the alarm to volunteer firefighters, and Amanda O’Brien and her brother would race to answer it. They knew those calls meant a ride to a fire with their father, David Deason.

“He’d always say, ‘stay in the truck,’ but we never stayed. We’d always get out and watch, and it’s just neat to watch the lights and everything that went on,” O’Brien said.

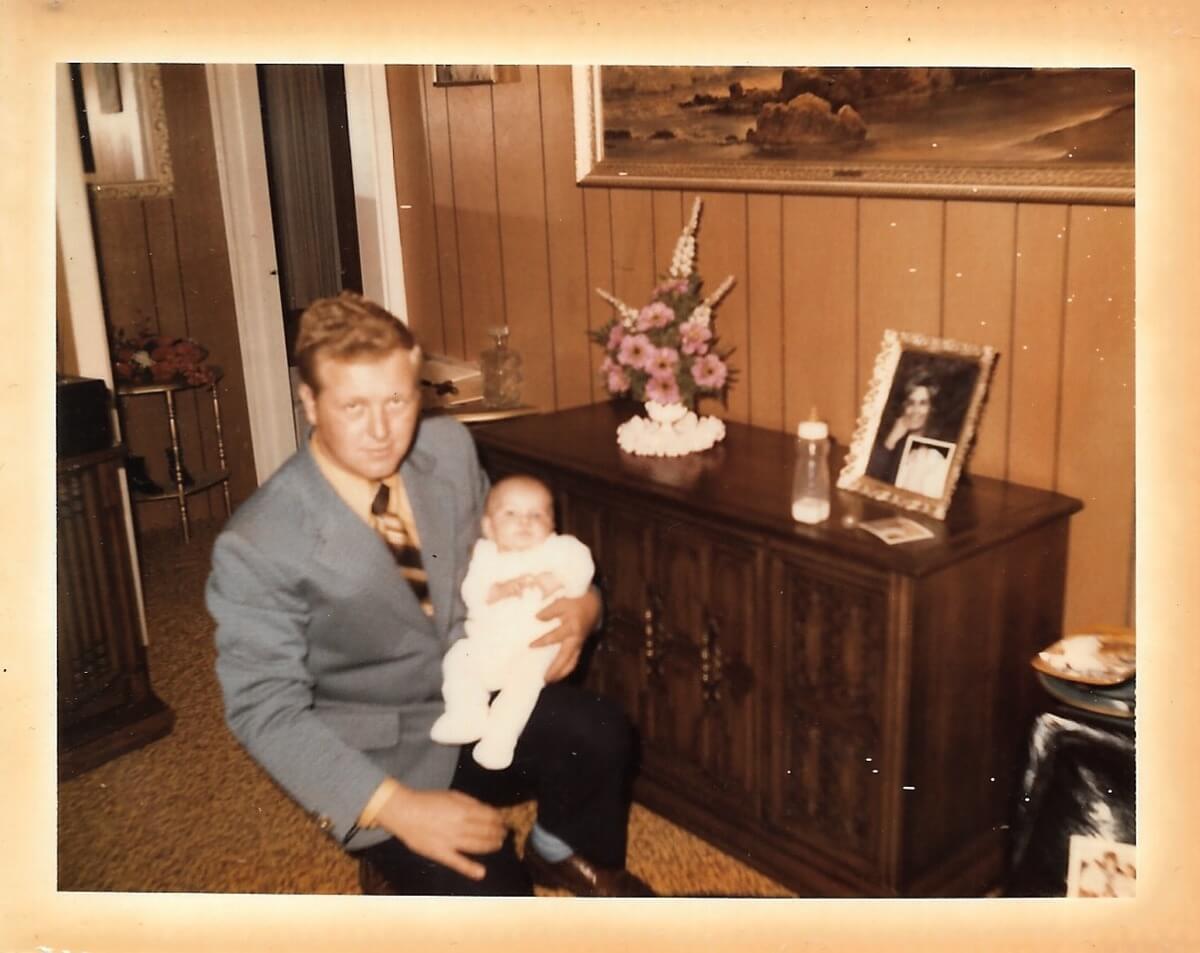

Her Papa John, Johnny Deason, had firefighting in his blood back to his childhood, too.

O’Brien said, “He’d always tell stories about beating the fire truck on his bicycle. That’s how long he did it.”

And he was hard to beat to the scene. O’Brien recalled being an 18-year-old volunteer and being with her Papa John when a call came in. She told him she was going, and he said he wasn’t but beat her there.

O’Brien’s firefighting career started in the department’s explorer program when she was 14 or 15. She became a volunteer with the Shelbyville Fire Department, like her daddy and her Papa John, when she turned 18. After two years, she was hired by the Shelbyville Fire Department and completed the required fire schools one and two. Although not required at the time, O’Brien challenged herself to complete smoke divers training.

“It’s a physical and mental challenge with your air pack. They put you in situations where you run out of air, and your mask will suck to your face. You can’t be claustrophobic; you have to crawl through tiny tunnels with all the added weight of your gear — more than 115 pounds,” O’Brien said.

In her case, that’s as much as O’Brien weighs, all on a 5’2” frame. She knew the training would show her weaknesses and her strengths. Stronger in her legs than her upper body, O’Brien completes annual agility tests while dragging a 250-pound dummy.

She said, “A man can just pick him up, throw him over the shoulder, and go, but there are so many different ways to train your body to do it.”

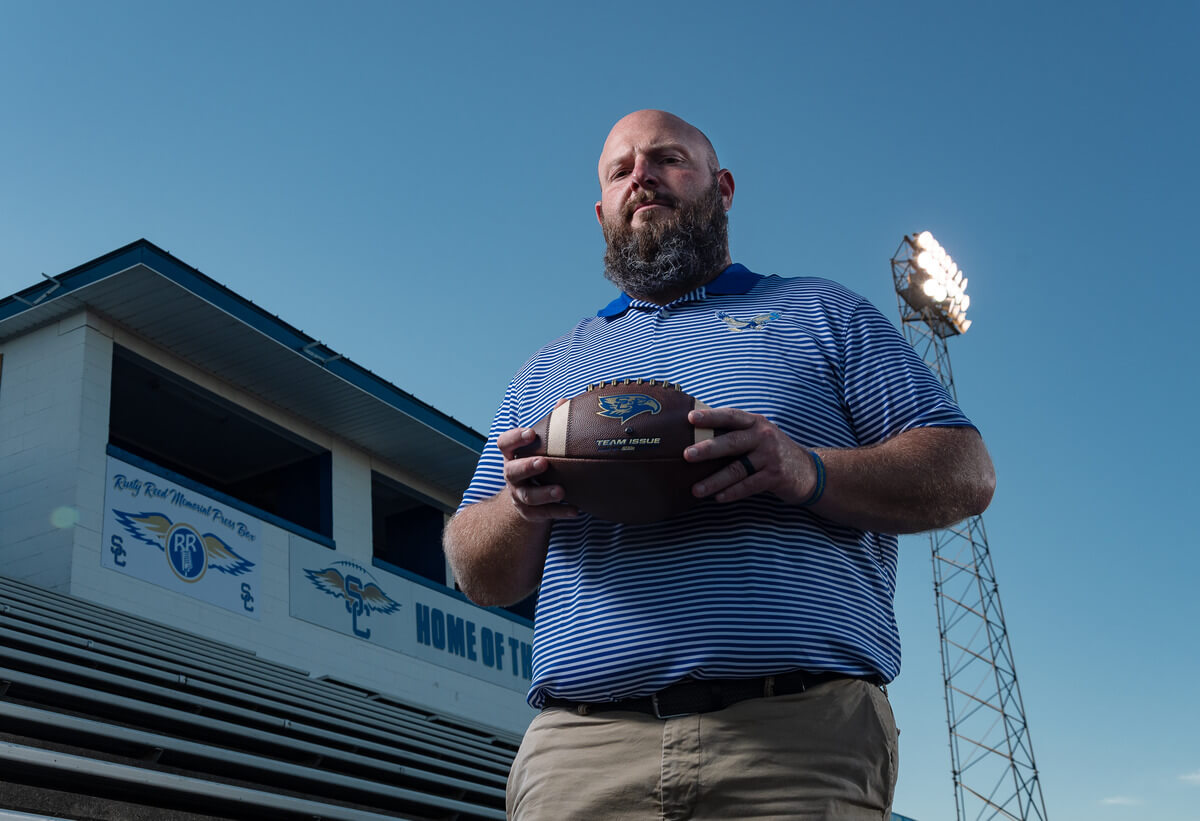

As an engineer, she’s responsible for driving the truck and managing the water supply at the scene. If you pass her on the way to a fire, you might look twice to be sure someone’s really behind the wheel.

“I struggle. I can reach the pedals, but there’s a siren on the floor I can’t reach. Being the shortest, I push my seat all the way up, so I feel for the guys that come in after me because their knees are in their faces. I get a lot of funny looks at red lights, too,” O’Brien said.

The responsibilities and weight of her job are a reality and not something she takes lightly.

She said, “When the tones drop, you don’t really think about it, but when you get back, you think about the fact that you’re responsible for getting these nearly million-dollar fire trucks to a scene unscratched and for the crew onboard, and the water for the guys in the house fire.”

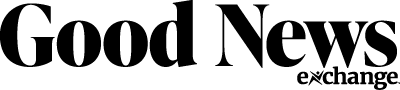

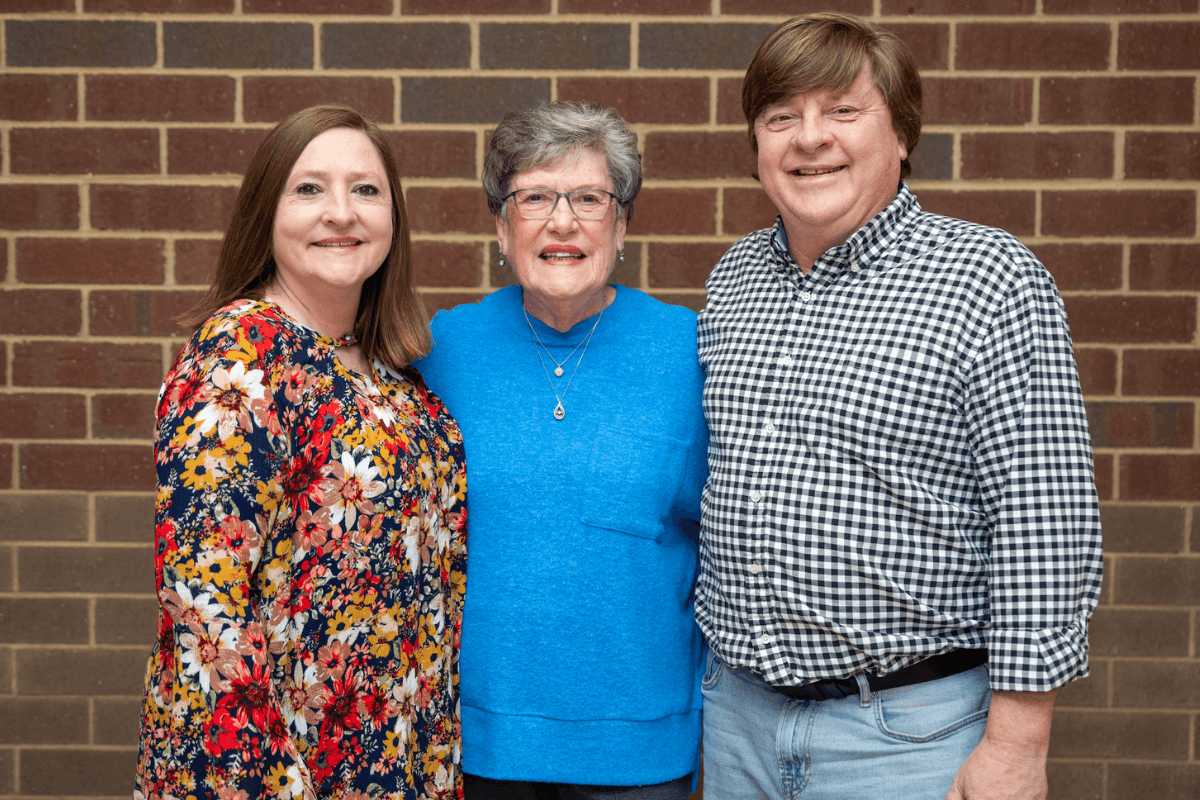

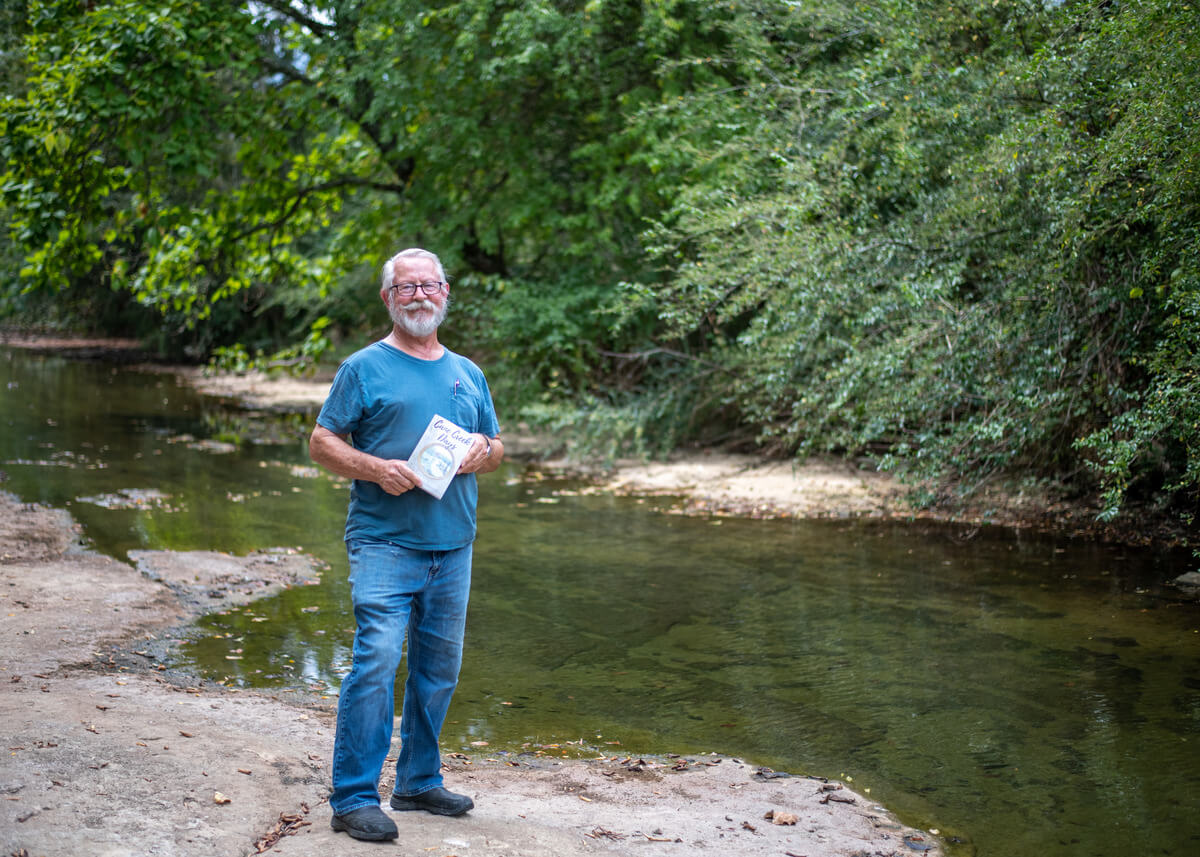

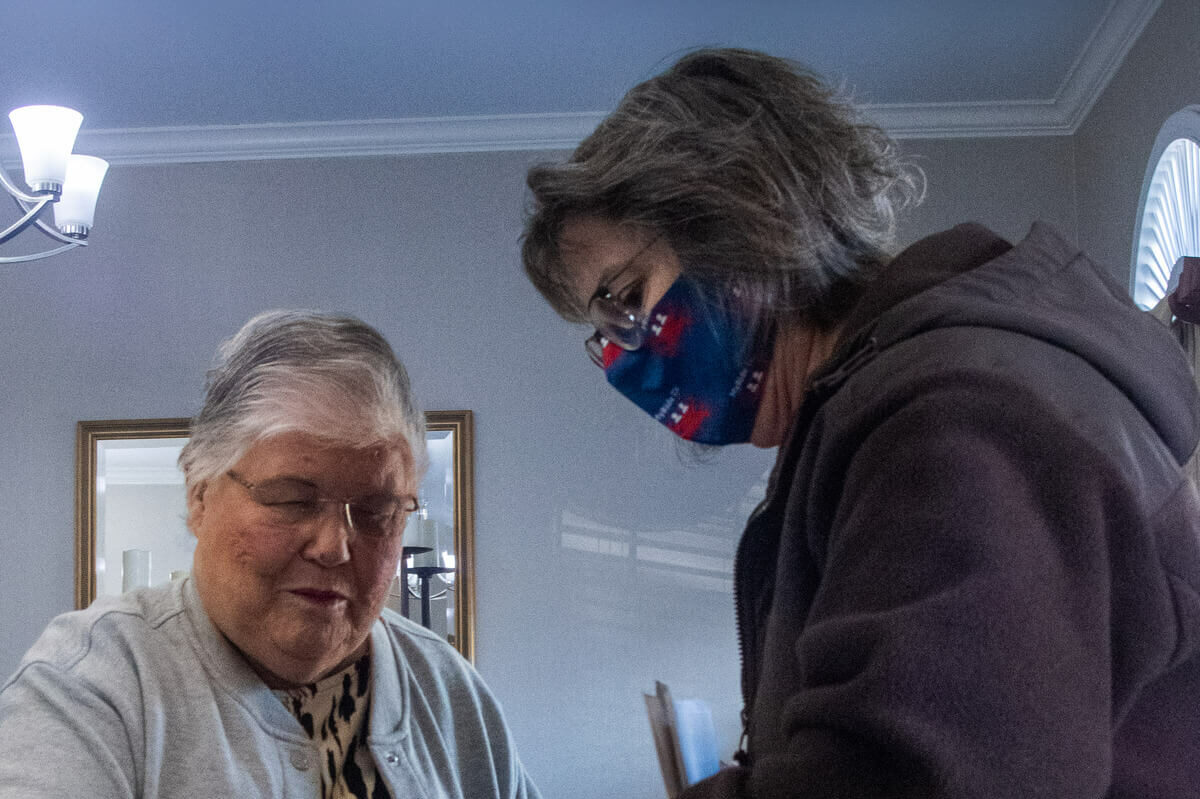

O’Brien works at the same stations where her Papa John served his community during his 67 years as a firefighter. In 2013, the community celebrated Johnny Deason Day, honoring his long-standing commitment to protecting our lives and property. Papa John passed away in 2016. Funds received in his memory were used to update the back engine room at Station No. 1. A plaque on the wall honors his legacy, and his granddaughter continues it by inspiring girls and young women to follow in their footsteps.

Her daddy, who served for 40 years, is proud of his girl.

David said, “Her being the first female engineer made me very happy. She showed me that a woman can do it, and I’m just proud of her. I’m very pleased when her officers and people over her tell me what kind of job she does. It’s so exciting to see her driving [to a scene]. That’s my little girl!”

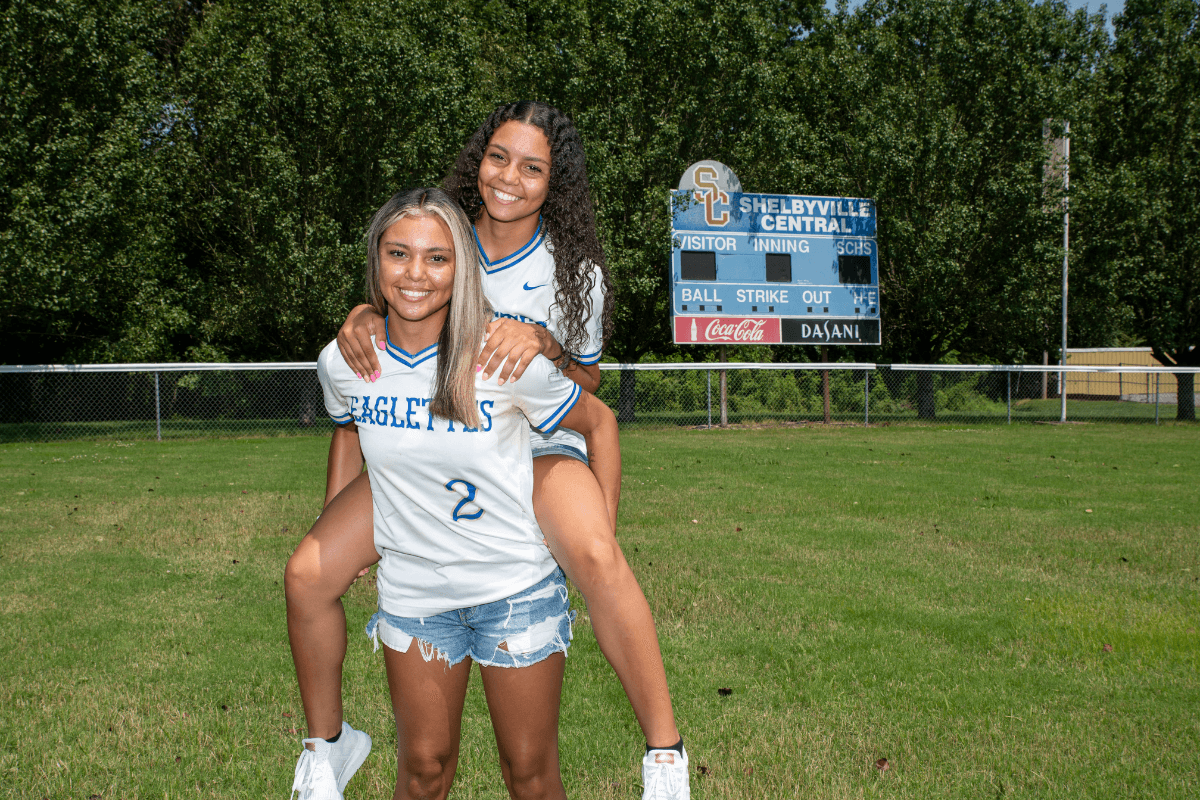

And it’s not just her daddy watching as she maneuvers the truck in and out of traffic, sirens blaring. Thanks to her example, many will do a doubletake to see who’s behind the wheel, including future female officers.

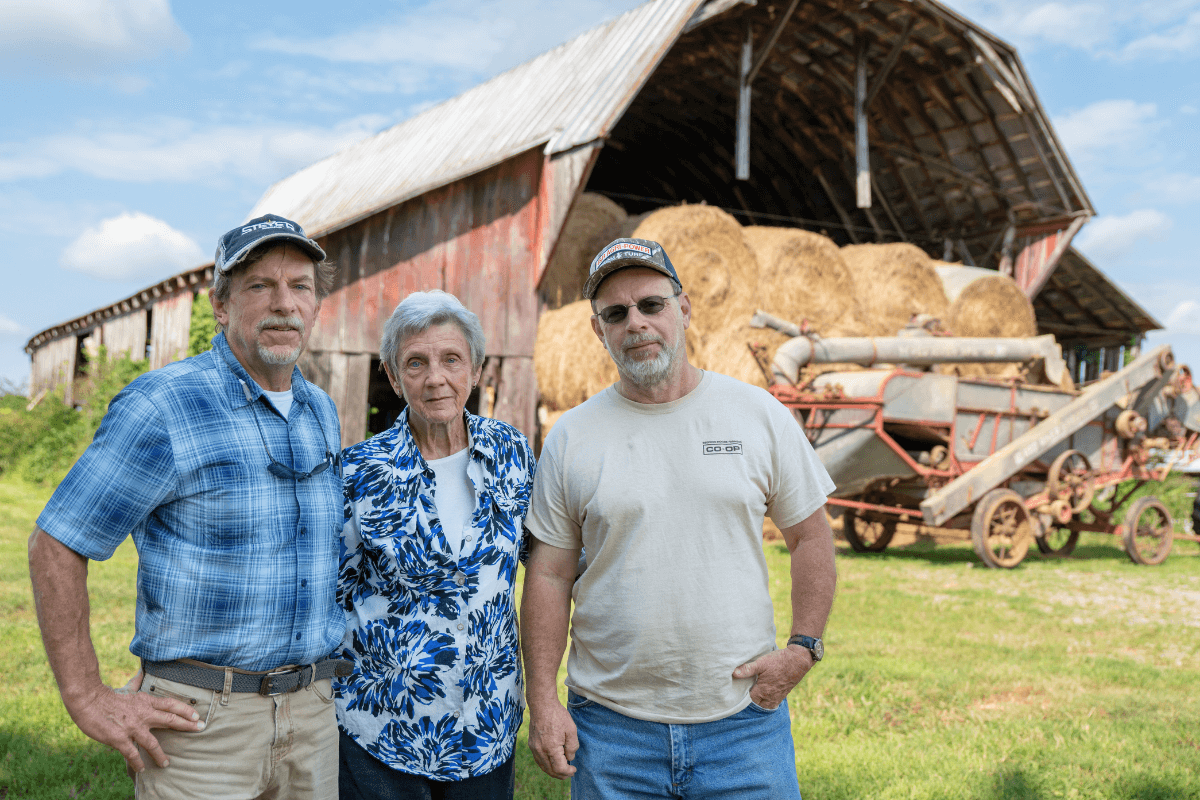

O’Brien said, “Driving through red lights, running lights, and sirens in these trucks, little girls are looking. At one call, a little girl came out to the truck and said, ‘Do you drive it? I want to do that.’ So I hope maybe it will inspire the kids.”

O’Brien, who works 24-on/48-off shifts, inspires both on and off the job. She’s a wife to Caleb O’Brien and mother to a 13-year-old daughter, Ansley. Caleb is active-duty military and works in Tullahoma every day, but the two manage their farm, where they breed and raise show cattle and dairy cows. Life doesn’t slow down for a minute.

She’s not the little engine that could; she’s the little engineer that can and does. GN