CHRIS BROWN slid his card into the ATM and punched in his PIN. As he’d done many times before, he selected the amount of cash he wanted to withdraw from the bank in Fayetteville, North Carolina. Gears whined inside the machine before a receipt printed, and a metal tray slid outward, revealing crisp bills. He stretched his arm through the open window of his truck and pulled out his card and the receipt from the machine. But as he retrieved the cash, someone stepped out of the shadows, and suddenly a gun was pointed at him.

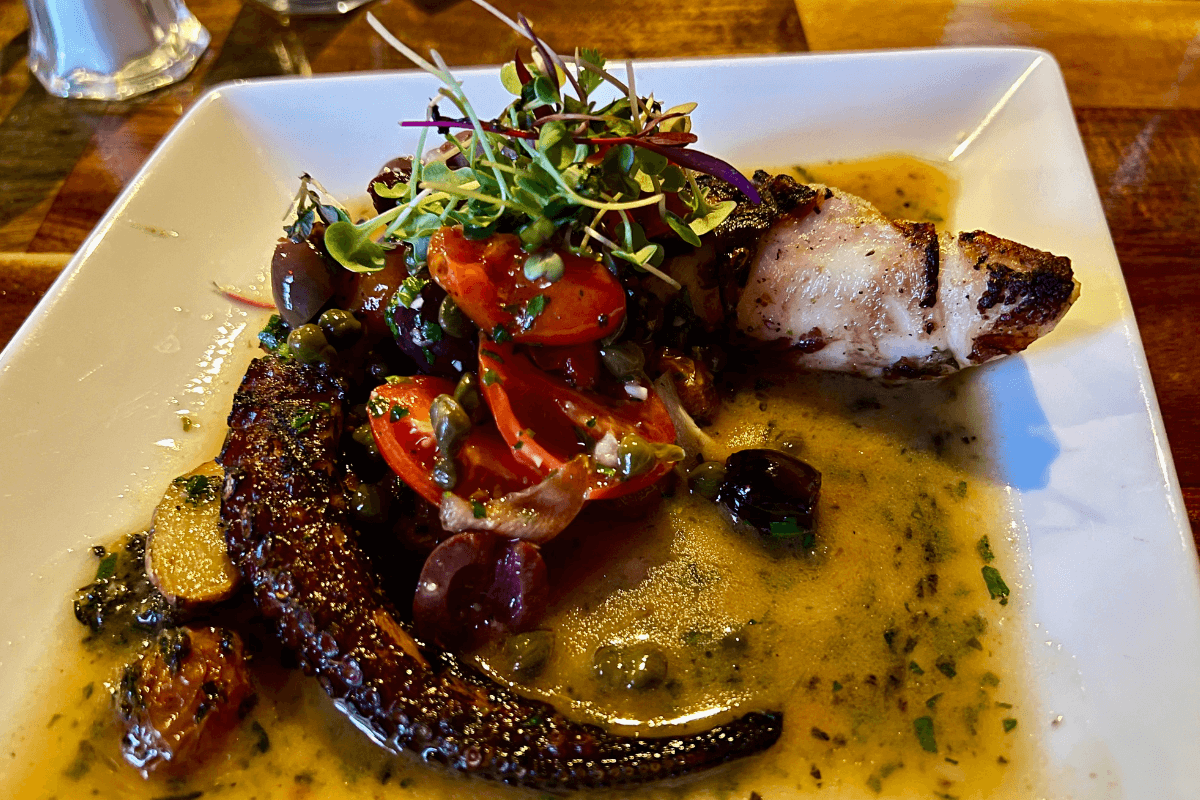

This memory hadn’t even faded when, a few weeks later, while waiting to be seated at a hibachi restaurant, bullets burst through the front windows. This unrelated incident turned out to be a gang initiation.

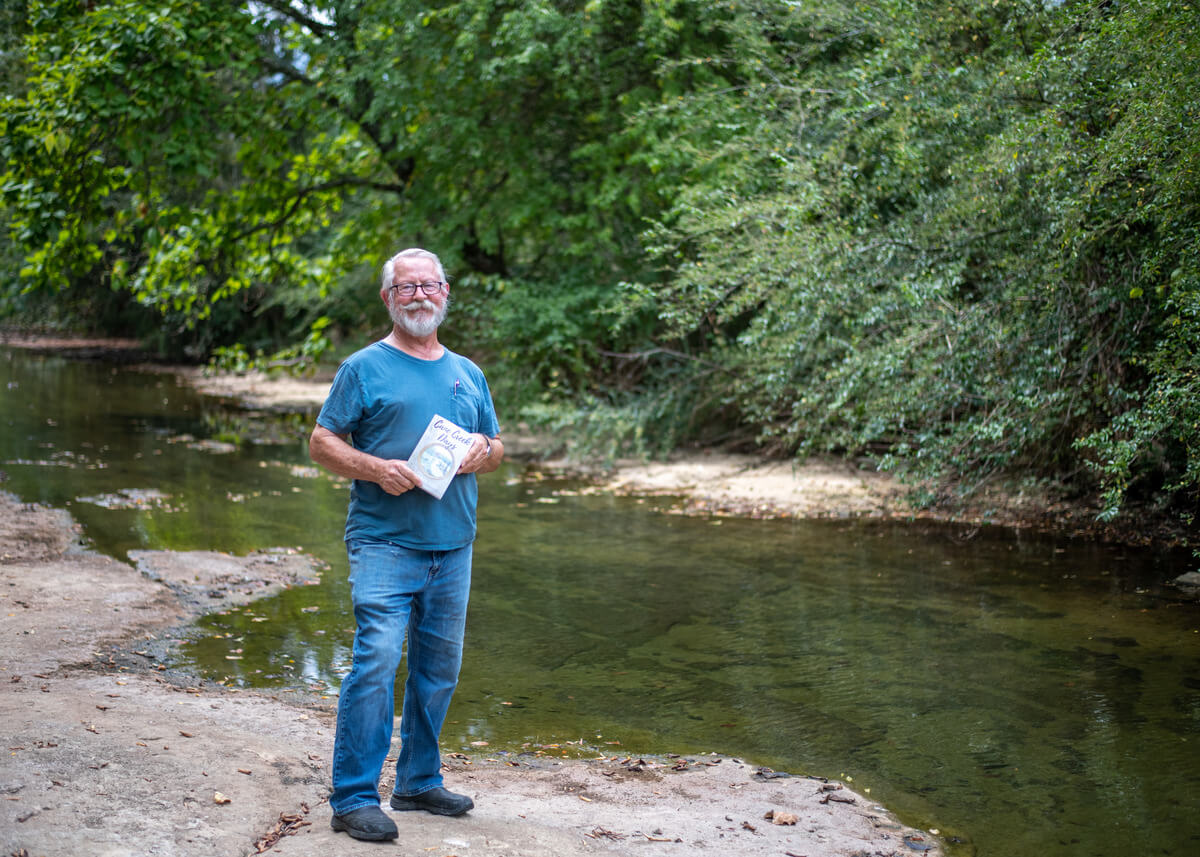

Brown had recently returned from serving in the United States Air Force. He was in North Carolina making plans to move back to his hometown of Shelbyville. While serving overseas, he and his squadron had provided relief to people in several developing nations. As someone who genuinely cares about the needs of others, he found this work to be deeply rewarding. He had dedicated four years of his life to making other countries safer, yet violence plagued his own country. This weighed heavily on his heart.

“I’d helped in [developing nations], but I knew right then that people in the U.S. needed help, too, and on both of those days I was one of them. From that point on, I wanted to be one of the people who received the call to help citizens,” Brown said.

In March 1996, at the age of 23, after moving home to Shelbyville, Brown reached out to then-Sheriff Clay Parker and his chief deputy, Dale Elliott. Brown recalled, “They took a chance on a young guy. They started me out working in the jail, and I spent six months there. I started patrolling the streets of Bedford County in September, and graduated from the Tennessee Law Enforcement Training Academy in January 1997. That was a proud day. I not only had my family present, but I also had the sheriff and chief deputy who hired me in attendance. I admired those two, so for them to see me graduate made me proud. I learned some very tough lessons from them about law enforcement and life in general, and I will forever be indebted to them.”

Even in those early days, Brown knew that law enforcement was his calling. “One of the very first days that I was riding with a field training officer, I was the passenger in a patrol car when I pointed out a vehicle sitting in the roadway on a rural county road. As we approached the vehicle, I could tell that the male driver was actively assaulting the female passenger. I was able to stop the assault and apprehend the suspect. This gave the victim immediate relief, and it felt so satisfying.”

Another time, he responded to a domestic violence call where a female victim had been shot multiple times, and the male subject had fled the scene. “While I was rendering first aid, I was able to get the subject’s name and identifiers from the victim. I managed to keep her awake and communicating with me until emergency medical personnel arrived. Her life was spared that day, and she recovered from her injuries. I met her again years later, and she was very appreciative of the help she had received that day.”

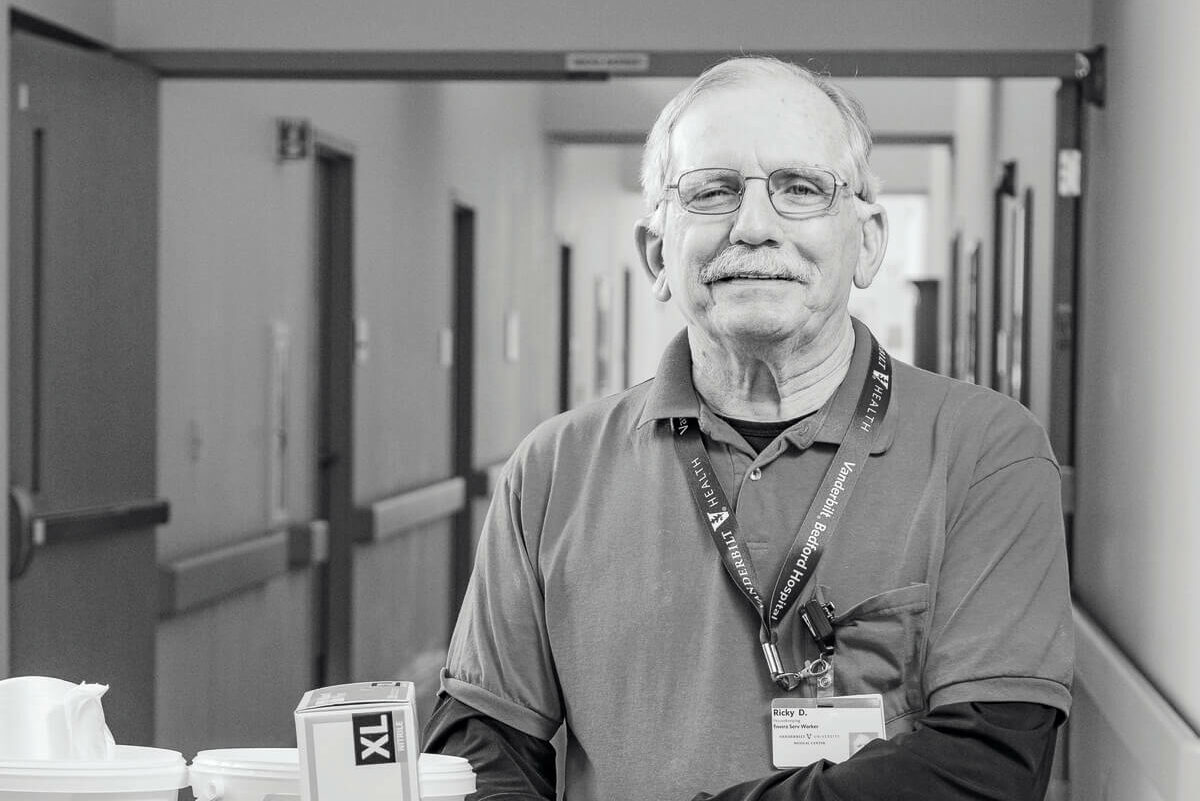

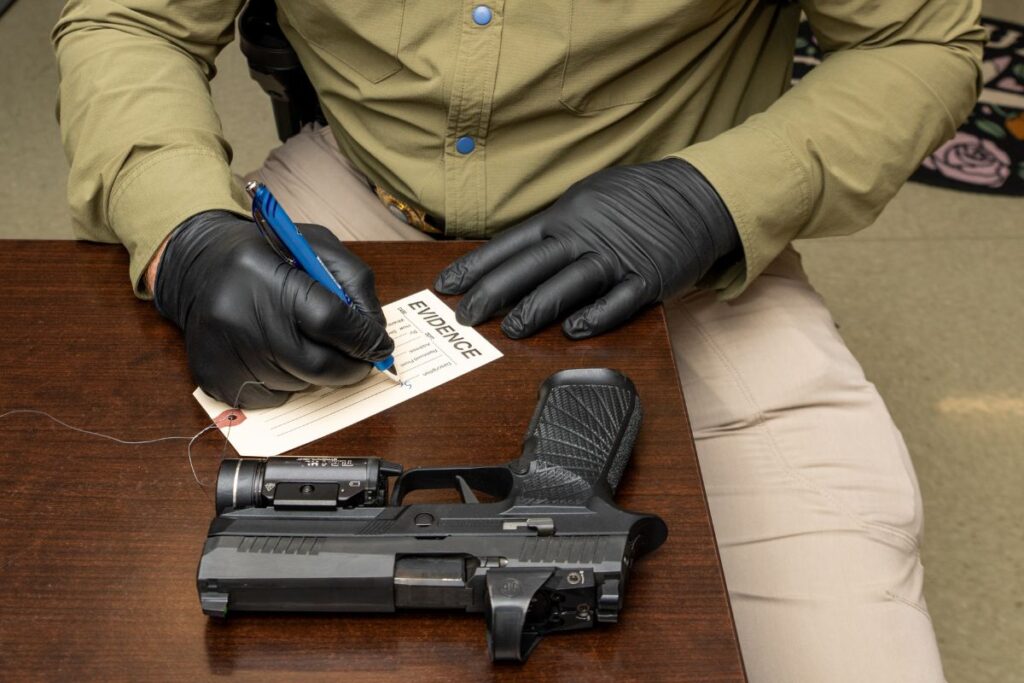

From 2001 to 2006, Brown worked as a detective with the sheriff’s office. He then spent three years as a court security officer at the Bedford County Courthouse before returning to his former position as a detective with the criminal investigations division in 2018. This time, however, Brown had moved up the ranks to earn the title of detective sergeant.

Brown has been credited with investigating and prosecuting several high-profile defendants and keeping them off the streets. But as the numbers on our census swell, so does crime. Brown said, “The daily reality of the job is that we, as detectives, only solve a small portion of the crimes committed. A lot of crimes go unreported, and others fall victim to people not wanting to prosecute after the initial report has been made. Sometimes, we don’t develop leads that allow us to charge someone for the alleged crime. But when we can put a case together and bring the alleged perpetrator to justice — that is very satisfying.”

Over the years, Brown’s chair at the dinner table has been empty on special occasions, celebrations, and even on holidays. Sometimes his phone rings before his alarm clock buzzes. But through it all, he said, “It is still worth it. If a young person is considering a career in law enforcement, I’d say to them it’s the most satisfying job you can do. If you can impact someone else’s life in a positive way, that’s a good day.”

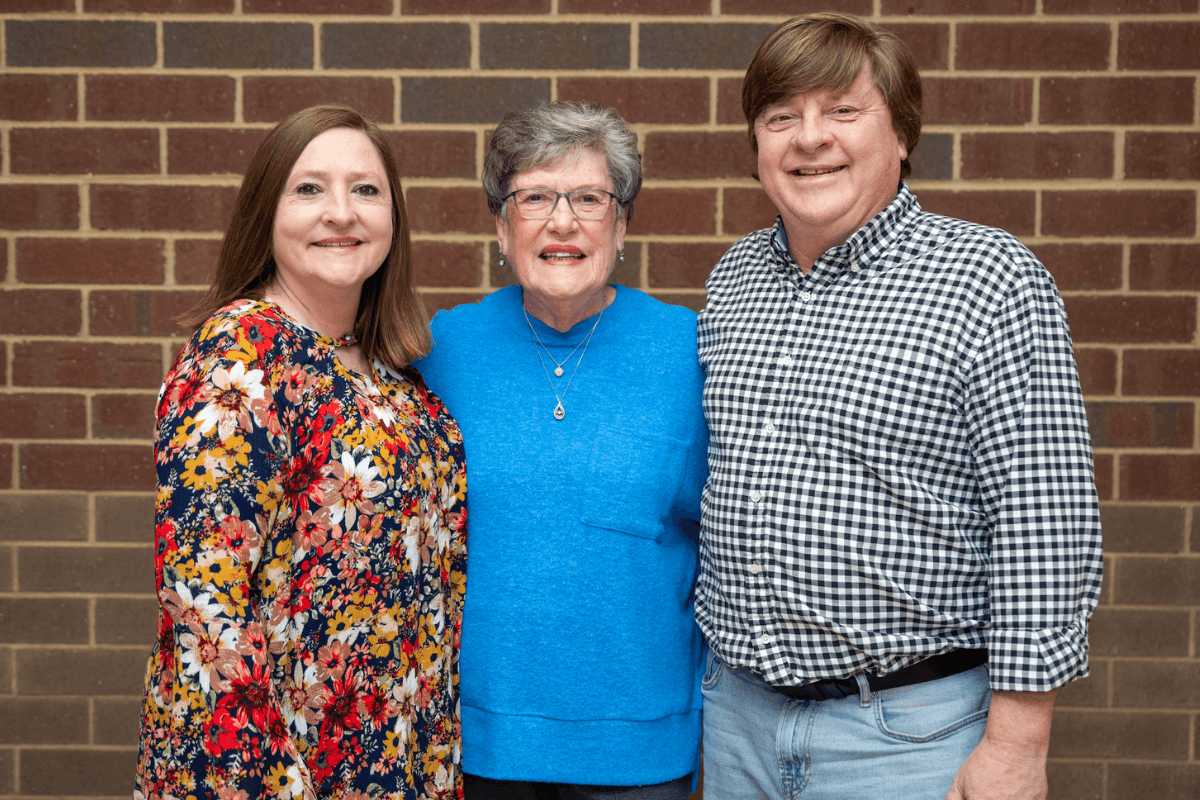

When all is said and done, Brown said, “I’d like to be remembered as a fair and honest supervisor as well as someone who loves God and his family, and as someone who cares about the community that I provided a service to.” GN