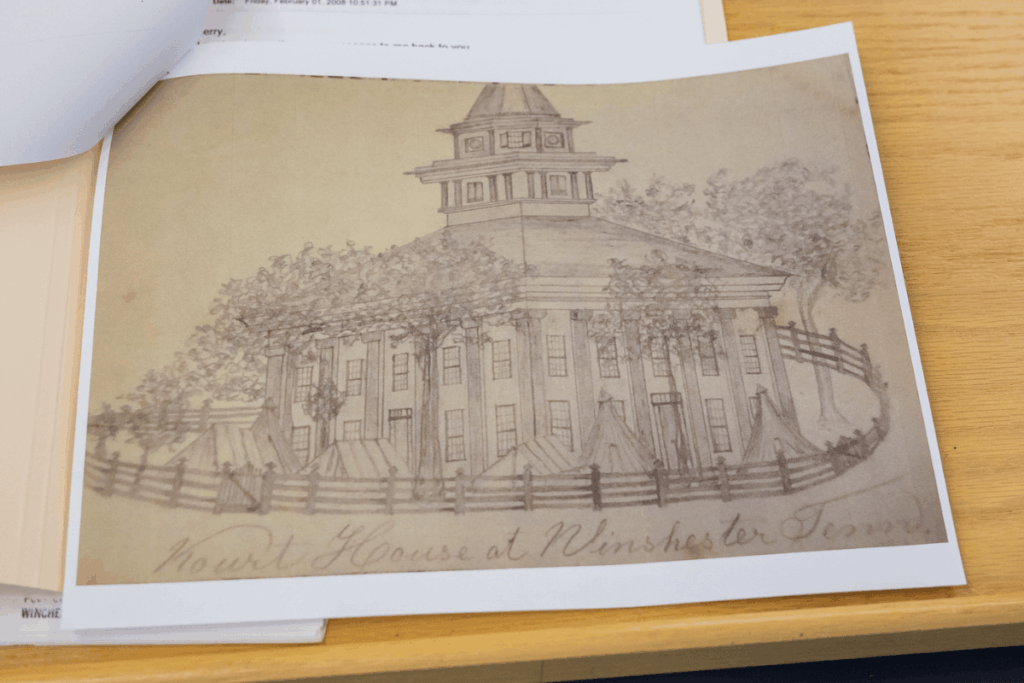

IT WAS 1862 when the typically quiet town of Winchester faced an unwelcome disruption. Embroiled in the Civil War, Union soldiers came to occupy the town, and though they would not take innocent lives, the troops thoroughly ransacked the Franklin County Courthouse, home to the town’s most important documents and valuables.

Locals watched in dismay as Union soldiers rifled through safes, scattered papers across floors, and demanded keys from frightened civilians to raid locked rooms. Thankfully, no one was hurt in this intrusion, but much was lost.

During the Civil War, when opposing troops came through a town behind enemy lines, they often occupied the area until they moved to the next destination. This frightening experience for locals was only the beginning of the violence that would reach Middle Tennessee during the war.

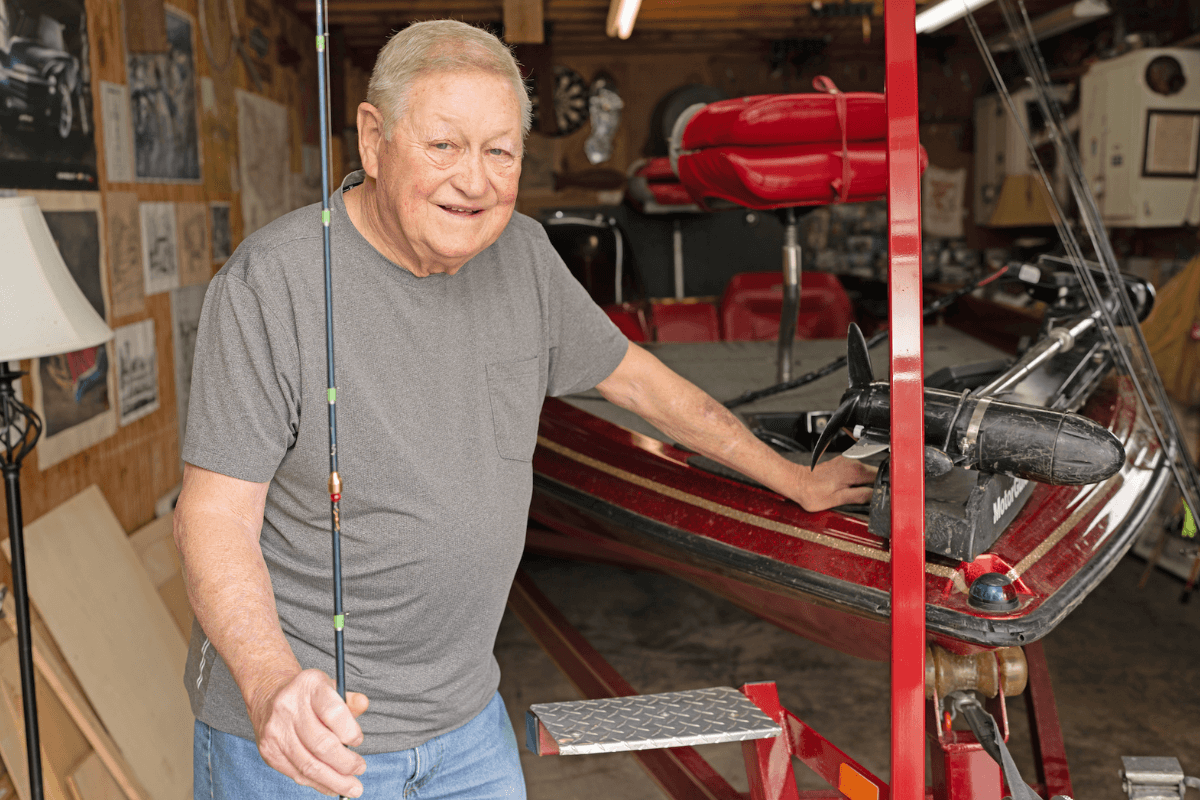

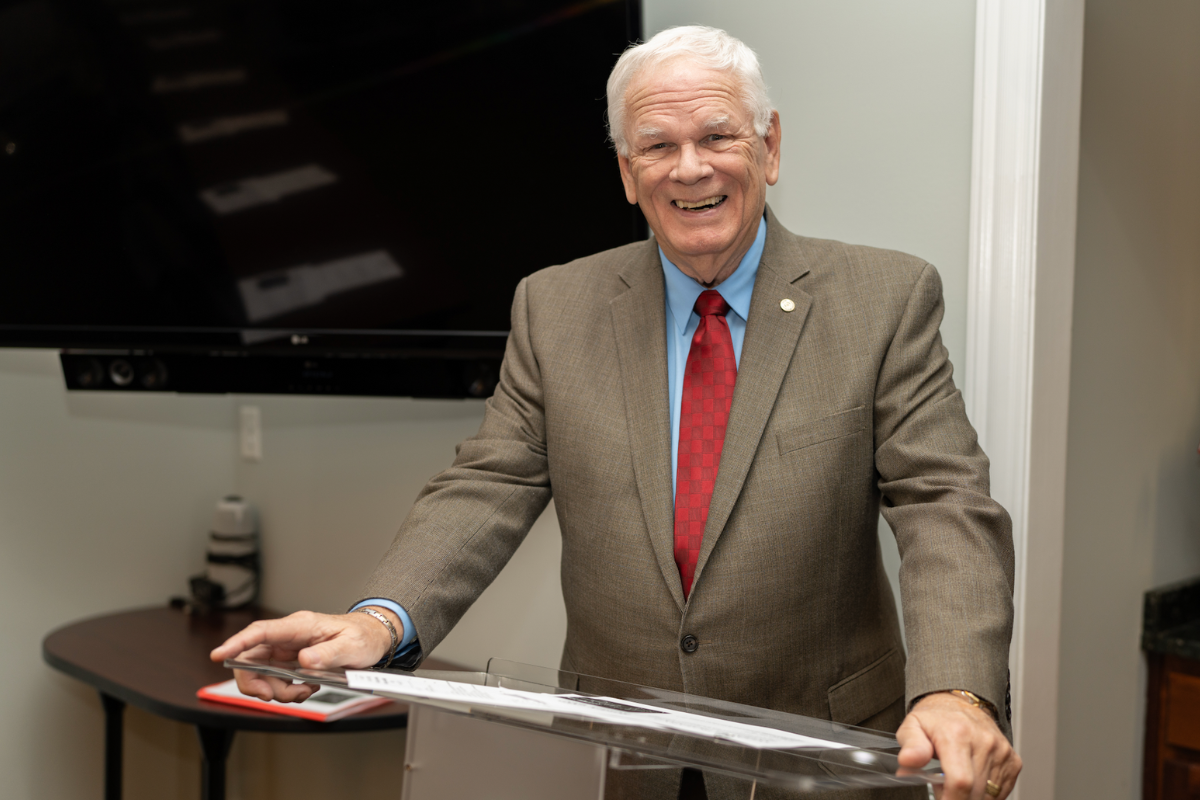

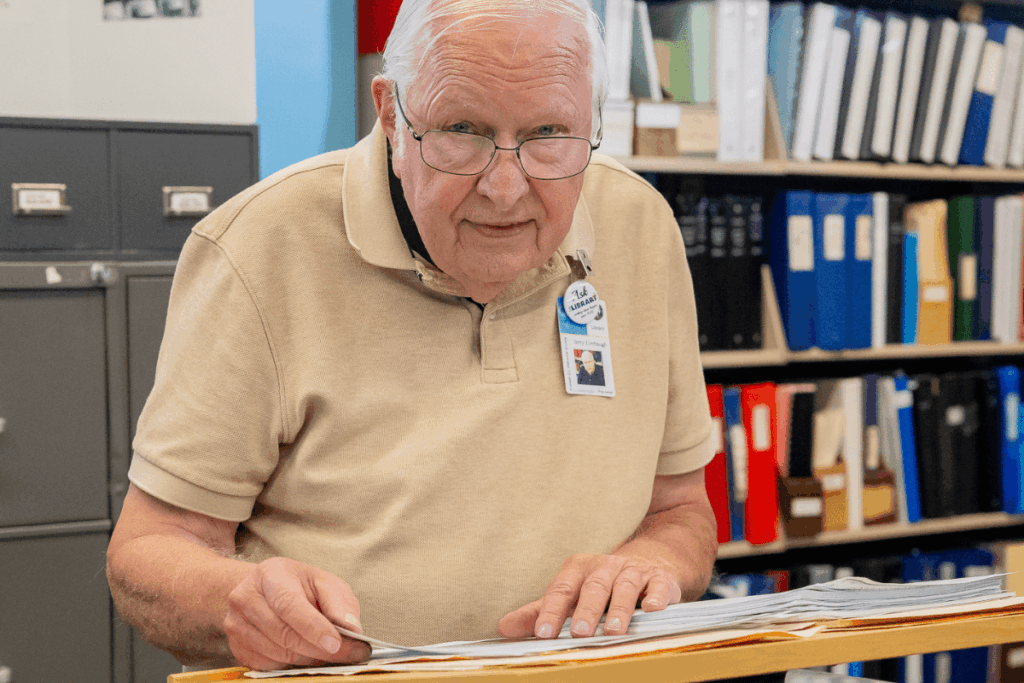

The Union Army passed through Tennessee on its way to Kentucky after the Battle of Shiloh in April 1862. Winchester was a convenient stop along their route, but they would not be there long. Franklin County historian Jerry Limbaugh said that even though it surely frightened the locals, he believed it was a “peaceful takeover.” The soldiers ordered civilians to leave, pitched tents around the building, and set up their own temporary headquarters. They were not there for the people, but for the bounty.

The soldiers focused on finding a melange of valuables: money from the courthouse safes and cash from local businessmen such as John W. Custer. They also stole horses from all over town.

A.S. Colyar, a wealthy local lawyer, lost a significant amount in this raid, including his personal law books, valuables from his safe, and a rare find: a prized Arabian stallion that Colyar had recently imported from Syria. The fact that he owned such an animal teaches us a lot about the international connections that existed in pre-war Franklin County.

Limbaugh believes Colyar may have written the Atlanta newspaper article, which is the only surviving account of the incident.

“This is really the only account I’ve ever seen of what actually happened during this time here in Franklin County,” Limbaugh said.

Flipping through the pages of the deed books today, you can still see where soldiers took time to sign their names simply to let future readers know they had been there, like a graffiti tag. These were the only community records that survived intact, with many more documents destroyed. Court minutes covering a 55-year period starting in 1807 were lost in the raid. All of the earliest paperwork detailing how Franklin County was started and who was in the community in the earliest days was wiped from history forever.

“Our records up until 1834 — the court actions, and all those types of records — were lost during this time,” Limbaugh said. This stolen history caused a lot of confusion and frustration for locals, and it is hard not to wonder what insights about life in Winchester those lost documents may have held. But what seemed like an inconvenience at the time was just the beginning of the escalation to come.

“This 1862 raid was sort of a precursor that gives you an idea of what was going to happen the next time in Southern Middle Tennessee and Jackson County, Alabama,” Limbaugh said.

When the Union Army returned in the summer of 1863, Bedford, Cannon, Coffee, Franklin, Grundy, Lincoln, Marshall, Rutherford, and Warren counties were occupied by soldiers charged with defending the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad; their headquarters were in Tullahoma.

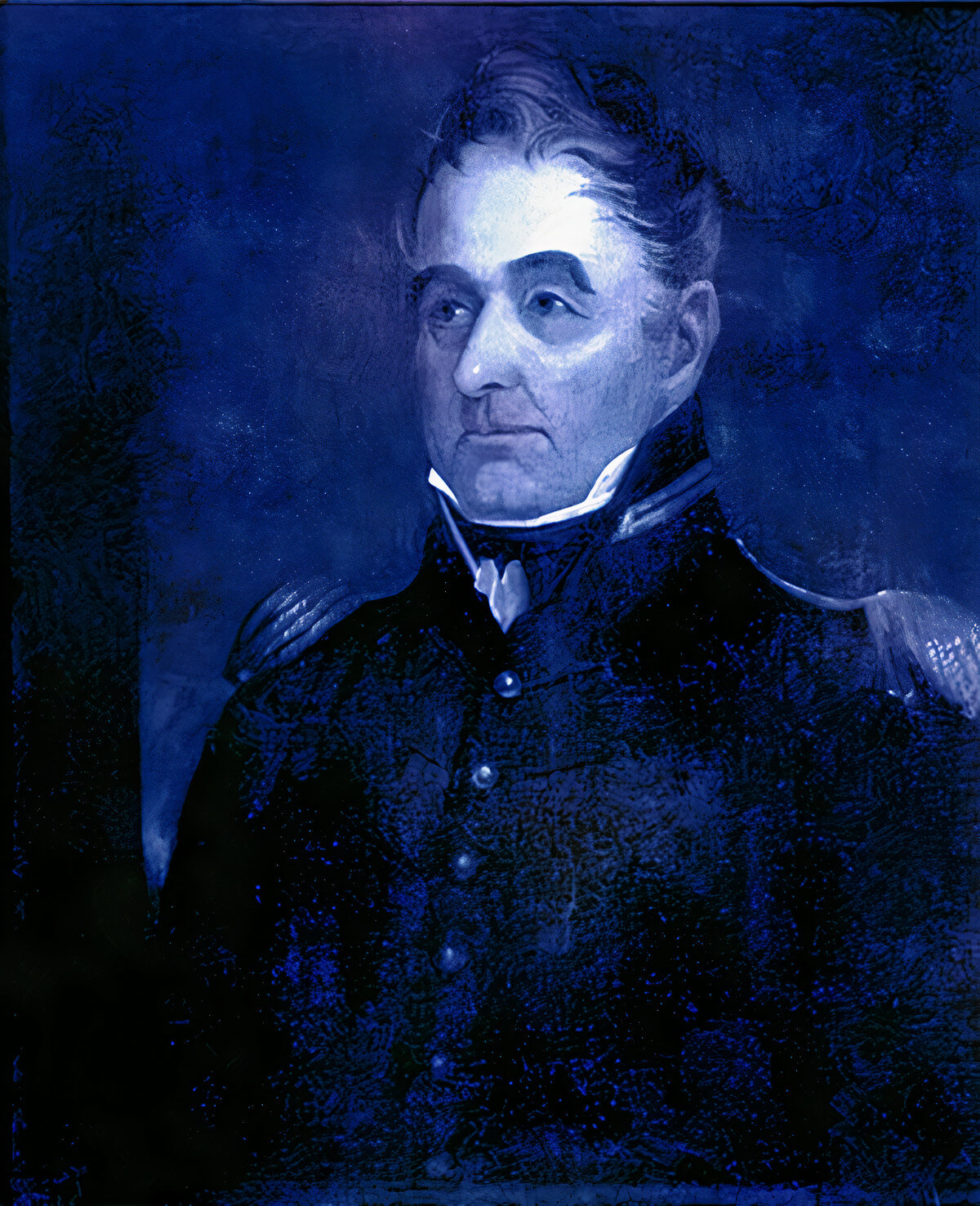

Maj. Gen. Robert H. Milroy commanded the division from 1864 until the end of the war. Gen. Milroy had a reputation for harsh treatment of civilians, including frequent banishments and public executions of those who expressed pro-Confederate sympathies. In his own words: “Blood and fire is the medicine I use. I shoot the men who are friendly with and harbor bushwackers and burn their houses.”

“Milroy was really a monster,” Limbaugh said, referring to the fact that the general had informants listing people who were sympathetic to the Confederate army. “He went down that list, with orders to burn this place down or kill this person,” Limbaugh said. Families were hunted down. People were killed in what Limbaugh called “hunting expeditions.” The brutality of war affected everyone who lived through those days.

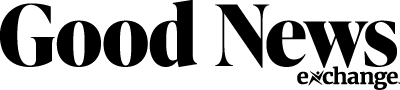

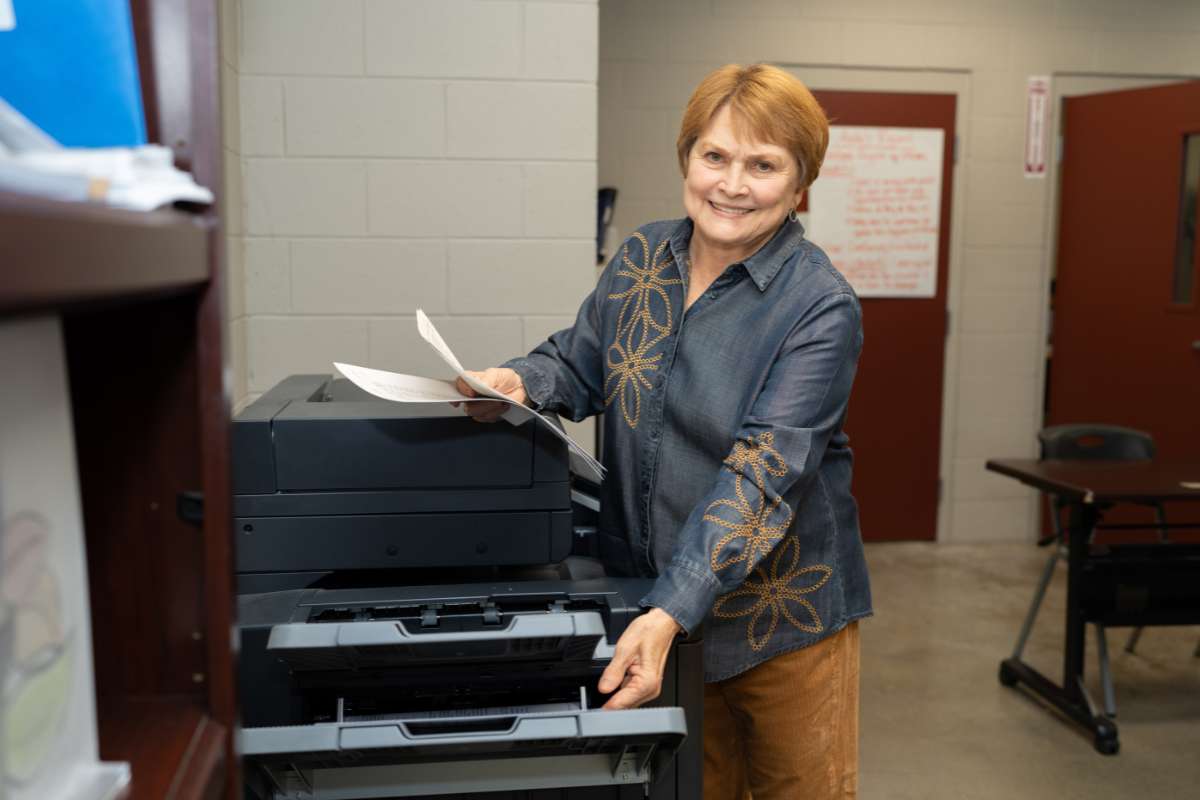

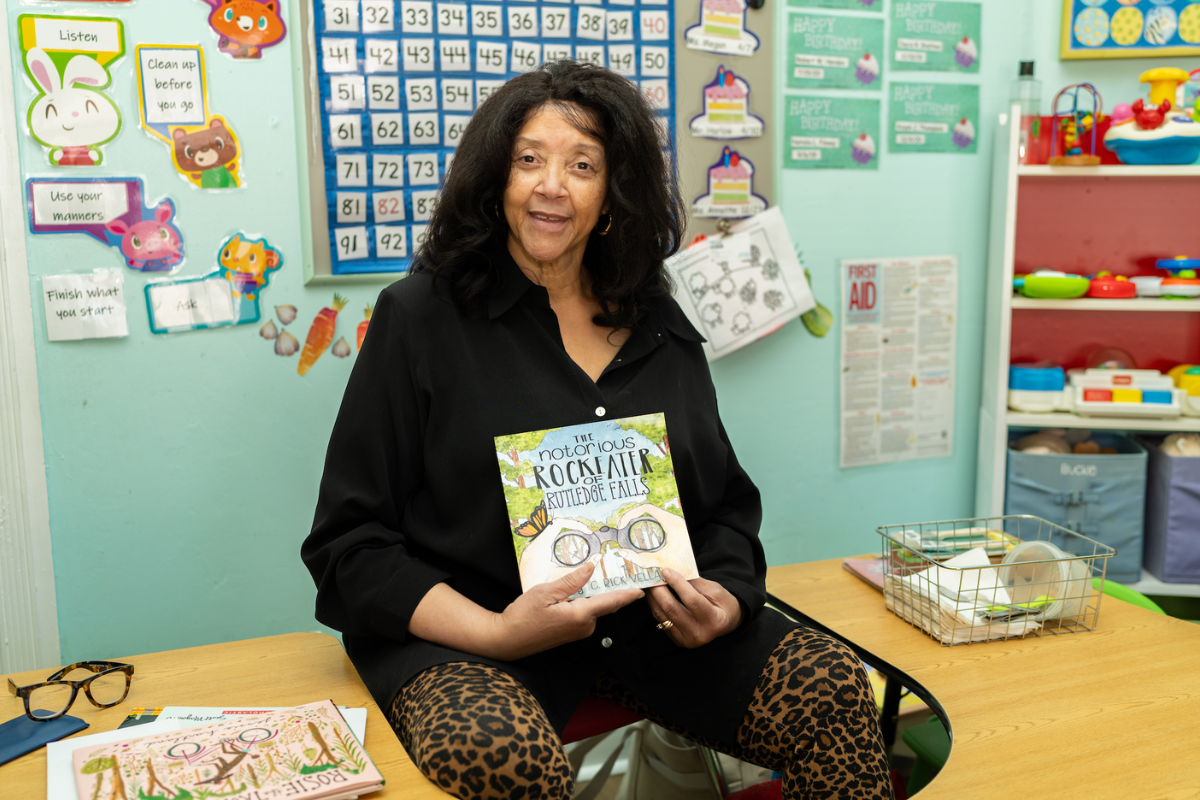

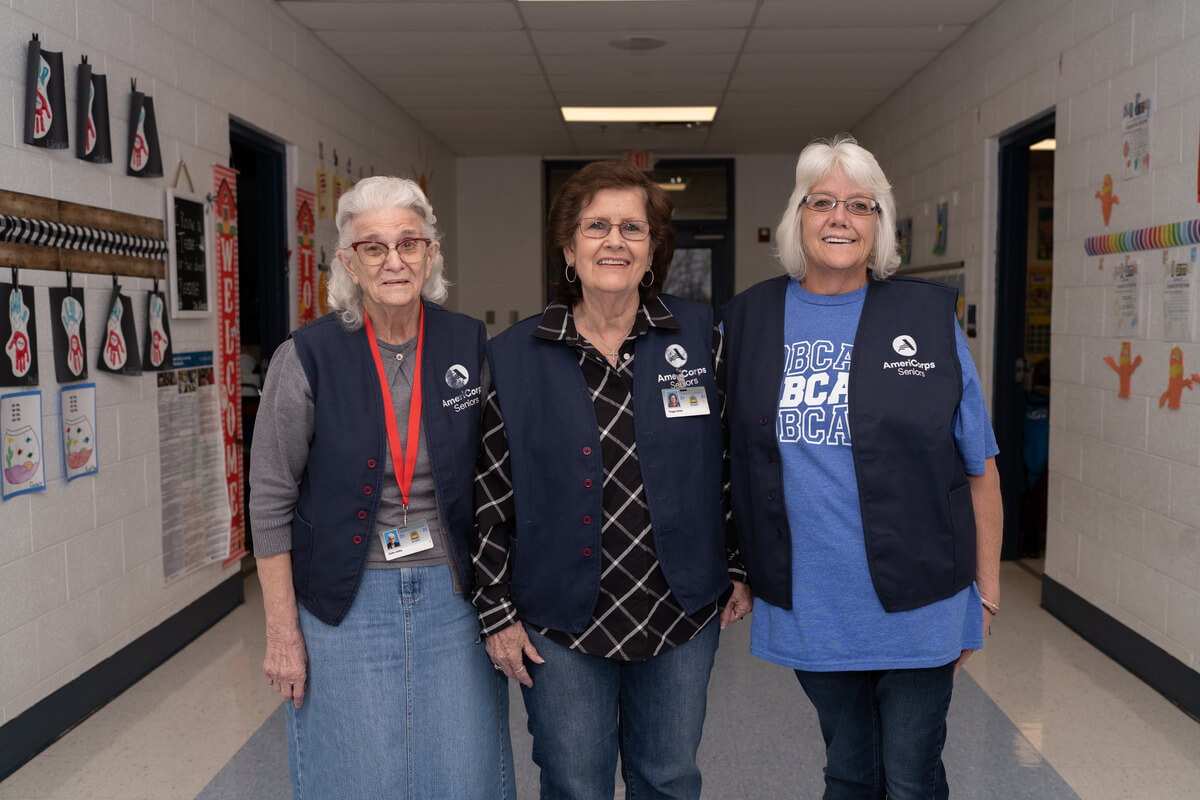

While incomplete, Franklin County’s history is carefully being restored and pre- served by locals, such as Jerry Limbaugh, who understand the value of learning from the past and understanding how our ancestors’ struggles and triumphs impact our lives today. He said that schools focus on large-scale history but do not take enough opportunities to dig into local history, which is rich in stories and valuable lessons. This is especially important for families who have lived in Franklin County for generations — knowing about your roots is priceless wisdom.

“I retired from the Air Force in 1991, and when I came back home to Franklin County, I volunteered with the historical society,” Limbaugh said. “I wanted to make sure this county’s history survived so we don’t forget about what happened in the past.” GN