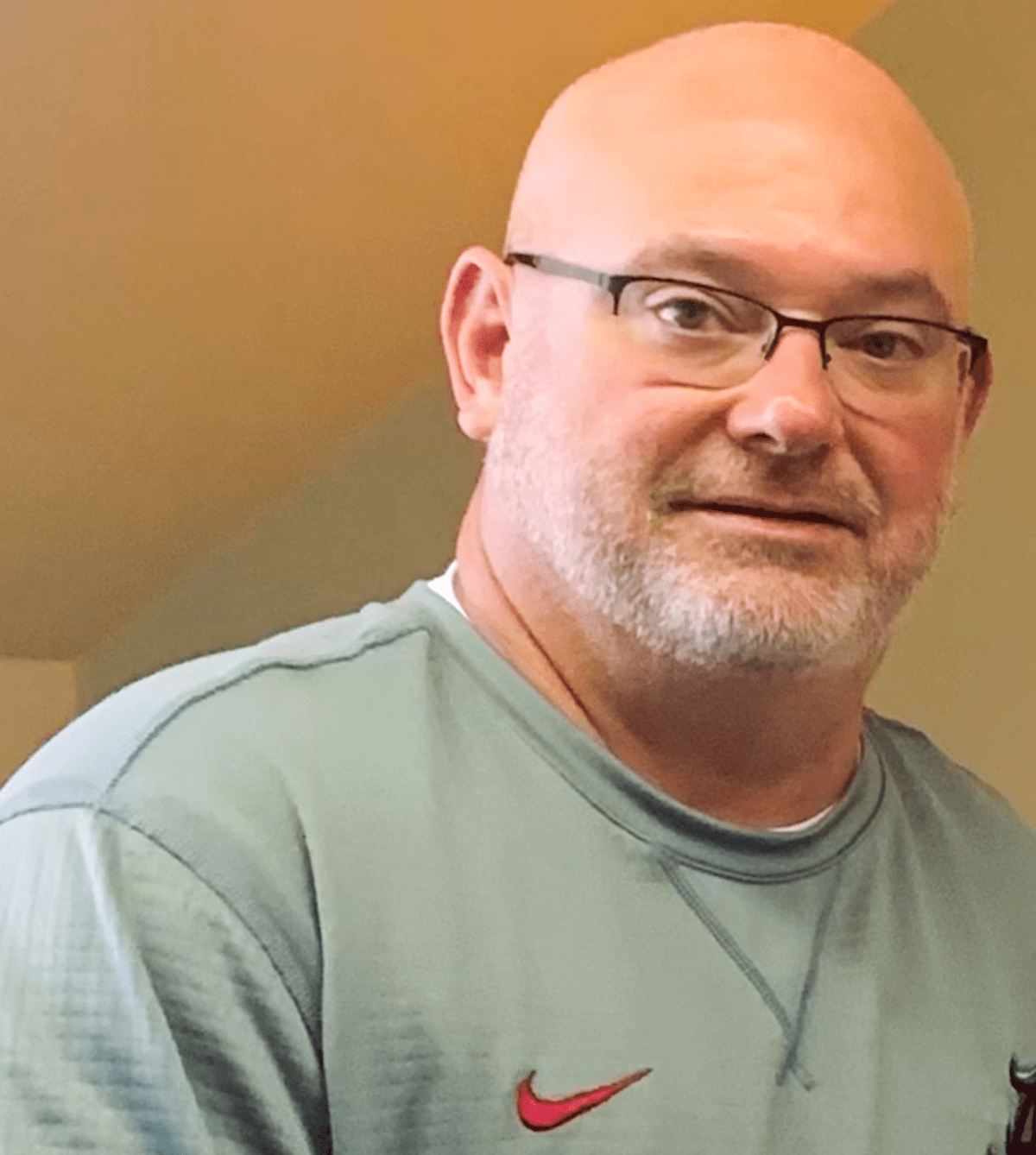

THE OFFICE’S furniture and decor matched his job description — drab and mundane. When Warren Bill Trimble hitchhiked from Sheffield, Alabama, to the Birmingham enlistment office in 1946, hours on end in a creaky, wooden desk chair was not what he imagined. The Smith Corona Sterling typewriter, also drab in its military khaki and green, clacked as he prepared outgoing letters, memos, and reports. The zip and ding of the carriage return outpaced the hour hand on the wall clock by a long shot. Could it get any worse?

It could.

His sergeant had a date that evening, but only if there was a date for her friend.

“I don’t really go on blind dates,” replied Trimble to his invitation to join them.

“Well, tonight you do,” came the order.

The next morning, everything was brighter, even his desk job at Chamblee Naval Air Station in Atlanta. A bright, beautiful young woman whose “kiss could curl your hair” stole his heart.

“That girl could really kiss,” Bill said of his blind date, Doris.

More dates followed, and when Doris commented that she could go for a man who smoked a pipe and wore Mennen Skin Bracer, Bill couldn’t get to the PX fast enough.

Stepping off the trolley for their date the following evening, an aroma of a cool menthol mixed with sweet, toasted tobacco met her before her date was in sight. True to her word, she could indeed go for a man like that. They married seven months later.

“I still have the pipe and some Skin Bracer,” Bill shared, his voice conveying the wink of his eye.

He hated his first assignment, but its impact on the trajectory of his life is undeniable.

“When I took a test in boot camp, I could type about 40 words a minute. That separated me from the other guys,” he said. “So when boot camp was over, they needed a clerk typist in Atlanta, so one other guy [who could type] was pulled out and went to North Carolina, I went to Atlanta, and the rest of them went to Germany.”

As soon as possible, Bill traded his typewriter for the tools of an aircraft mechanic.

“I didn’t want to be a clerk typist. I hated that job, and I kept aggravating the sergeant to get me out on the line and let me work on planes rather than work on a typewriter. It took me a while to get that done, but they finally transferred me out on the line,” Bill explained.

When Bill transferred to Naval Air Station Glenview, the general he served under commanded all squadrons from the East Coast to the Mississippi River. Those squadrons routinely traded locations with the ones from the West Coast for training purposes. During one of those West Coast maneuvers, things were far from mundane for Bill.

En route to El Toro, California, their plane — heavily loaded with equipment, supplies, and fuel — steadily climbed to altitude. But something was noticeably wrong. The deep, pulsating rumble of the engines Bill always felt was absent, and the thunderous roar was swiftly decreasing. It was soon apparent that one engine died, and then the other engine failed.

“We’re coming in with a dead stick,” the pilot reported, according to Bill.

The situation warranted a forced landing.

While the pilot searched for a clear landing, mentally calculating the aircraft’s glide ratio, Bill went to work in the aircraft’s engine compartment, quickly assessing the situation while the pilot circled to land. Suddenly, the engines roared back to life, and the plane landed under full power. Bad fuel was the culprit; Bill was the coolhead.

The same calm, determined spirit followed the couple, their newborn son, Jeff, and Bill’s mother as they left Chicago in a 1947 Chevrolet with 4 inches of snow on the ground after his discharge in 1950.

Bill reflected in amazement, “We left at 8:00 that evening and drove all night and never hit a dry piece of pavement from north of Chicago to Sheffield [Alabama]. We drove in snow, onto ice, and then into rain. I can’t imagine how the good Lord got us through that.”

But they were driving into the rest of their life. Nothing could delay that.

Their family grew again with the addition of their daughter, Lisa. Bill took a job with South Central Bell, and their family later moved to Fayetteville in 1965. They still live in the same home.

Today, the Trimbles banter is sweet and kind, sprinkled with patience and contentment. Bill is still in awe of his wife.

He said, “I don’t understand how a woman with her abilities got hooked up with a dummy head like me. She was the top person in her class; she’s a brilliant person.”

“No, I’m not. I’m just me,” Doris countered.

“Yeah, you are, baby,” Bill reiterated. “She’s still beautiful, just hanging in there.”

She was fond of military life but is just as happy with life today.

“I enjoy life, and I enjoy people,” she shared. “Life is good. We enjoy our life.”

Bill agreed. “We’ve had a good life — 77 years in October.”

He’ll soon be 97 years old and is likely the oldest living veteran in Lincoln County. Bill’s mind is clear, and his words are thoughtful and endearing. Doris backs him up, and the two are obviously completing one another.

“We’re just sitting here watching the cars go by,” Bill said, but without any trace of bitterness or regret.

While it may seem mundane to some, it’s another day in a good life for the Trimbles. GN

On September 7, 2024, Bill’s world was forever dimmed by the loss of his brightest light, Doris. For nearly 77 years, she brought color to the drab and mundane parts of his life, even making sitting and watching the cars go by a gentle, beautiful way to pass the time. The final chapter of the Trimbles’ good life together closes, leaving only one watching the cars go by as Bill awaits the day he’s reunited with Doris, his world’s brightest light.