In Lincoln County’s courthouse, addiction’s grip tightened relentlessly. Judge Andy Myrick’s docket overflowed with repeat offenders, their charges a stark reflection of substance abuse’s grip on the community. Theft cases multiplied as desperate individuals sought ways to fund their next fix. In juvenile court, confused children faced removal from homes where addiction replaced parental care.

Overdose calls burdened emergency services, each one a potential death sentence. In quiet neighborhoods, empty chairs at dinner tables and unused bedrooms told silent stories of families torn apart. As Myrick took in the stark reality of disrupted lives and lost futures, he felt the weight of the community’s struggles. The need for a new approach was clear, and the seeds of the recovery court began to take root.

Myrick said, “Over the years, I saw the terrible effects of alcohol and drug abuse on our community: higher crime rates, destroyed lives and families. I was aware of recovery courts in other jurisdictions and that they were successfully being used to combat addiction.”

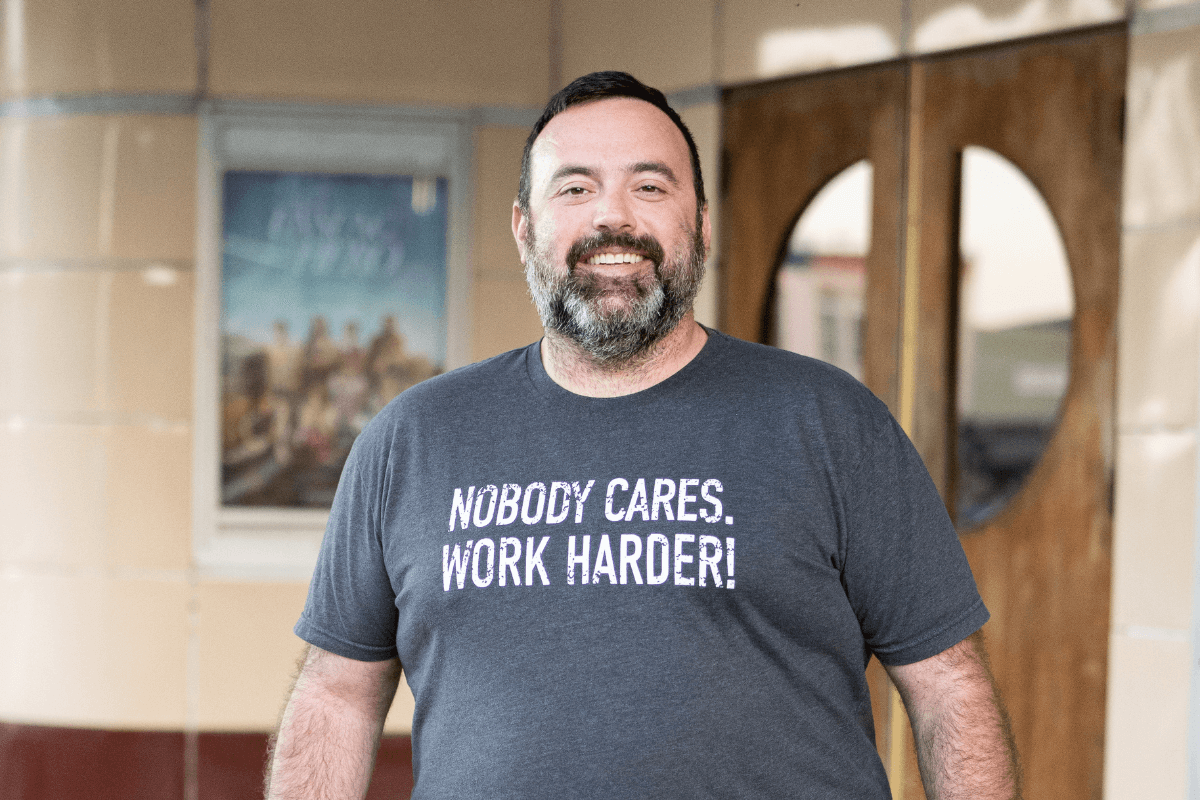

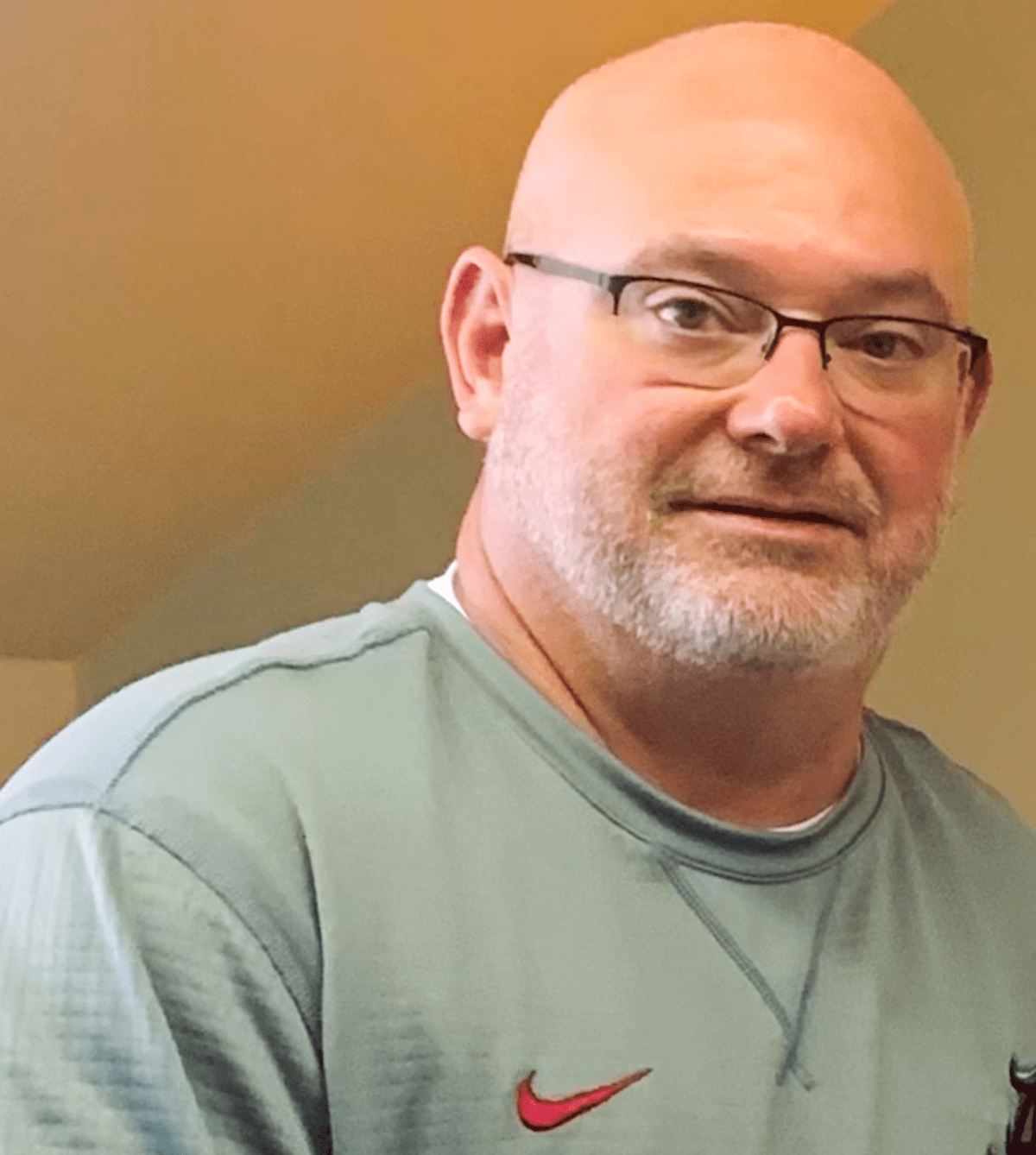

For Tony Patterson, the recovery court’s director, the devastating impact of addiction wasn’t just a professional concern — it was deeply personal.

“My wife was in active addiction for over 12 years,” Patterson shared. “I’ve been to almost every treatment center and emergency room within Tennessee, Northern Alabama, and even Southern Kentucky. In the end, I found my wife overdosed on her couch, and my administration of CPR was too late to bring her back.”

This tragic experience fuels Patterson’s commitment to the program.

“I do not want others to ever live through that horror. I’ll do what I can to prevent it,” he said.

In 2017, a grant from the State of Tennessee and the invaluable participation of the South Central Human Resource Agency (SCHRA) enabled the establishment of Lincoln County Recovery Court. However, not everyone immediately believed in the program’s potential.

“Many of my law enforcement friends were not too sure about the program… But when when they learned more about how the program works and saw positive, life-changing results in our participants, their minds were quickly changed,” Myrick explained.

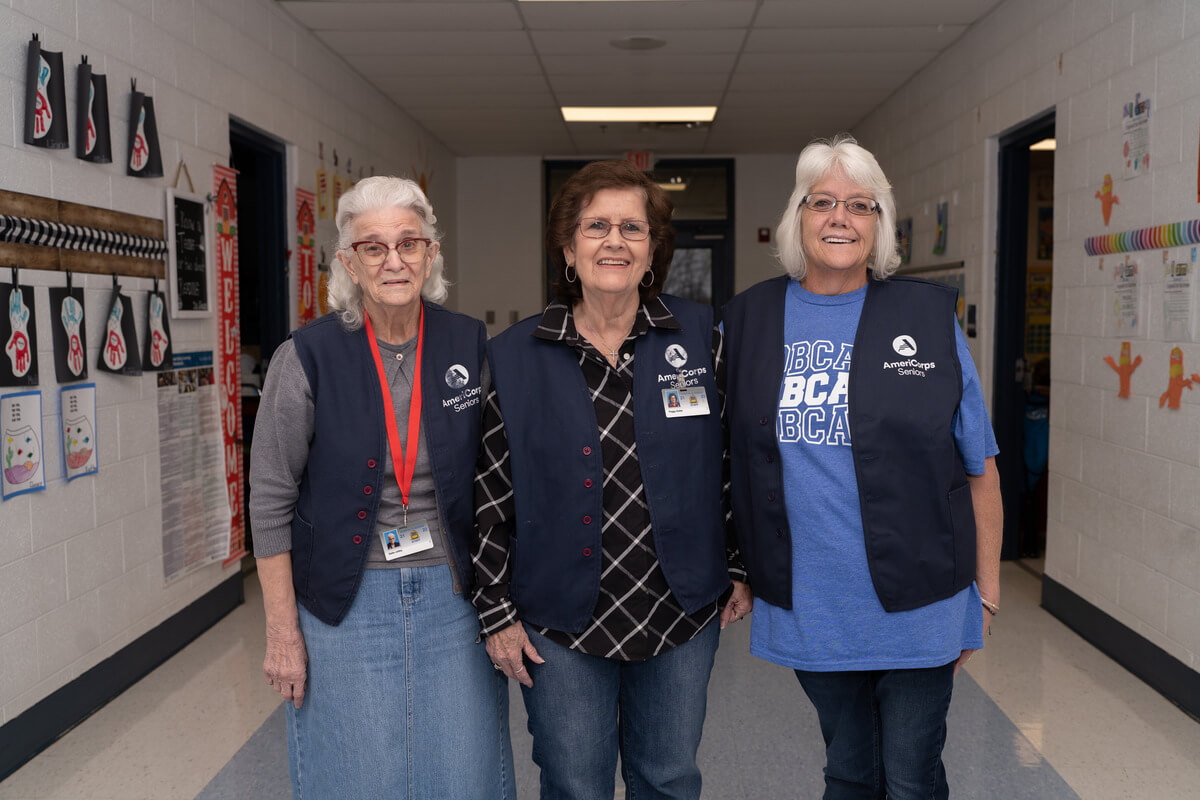

Myrick and Patterson credit SCHRA for their role in sustaining the program.

“We simply would not have recovery court without SCHRA. They obtain our grants, provide offices, provide treatment space, and pay our recovery court coordinators. SCHRA is the core of recovery court,” said Myrick.

Patterson agreed and said, “SCHRA shoulders the weight of this program.”

First United Methodist Church is another important source of support for the program. The church sponsors Celebrate Recovery, a Christian-based 12-step program, and hosts graduations and other events for recovery court.

“Participants in our program often seek support groups to attend. Celebrate Recovery is one of the support groups that many choose to engage with, and it has been instrumental in the lives of many participants,” Patterson said.

In Lincoln County, where addiction treatment resources are severely limited, the recovery court program relies heavily on its partnership with Centerstone. This collaboration, supported by a grant, enables access to essential mental health services, including intensive outpatient programs and relapse prevention.

According to Patterson, without Centerstone’s support, the program would struggle to provide the necessary treatment options. The absence of local sober living facilities and limited recovery meetings highlights the challenges faced by participants returning from more resource-rich environments. However, this partnership has been instrumental in addressing those gaps and fostering growth in Lincoln County’s recovery infrastructure.

Myrick stated, “We are a rural community, so our treatment resources are not as great as the larger cities. Our biggest challenge is sober housing — safe places for our participants to live where they will not be exposed to drug or alcohol use. [As Alcoholics Anonymous teaches,] changing ‘people, places, and things’ is critical for a person in recovery.”

Community awareness continues to grow through the tireless efforts of those entrenched in the local recovery court.

Patterson reported, “We’ve attempted to increase public awareness and acceptance of recovery and addiction through various avenues. We have started the annual recovery fest, which, this year, had approximately 500 in attendance. We are active with the Lincoln County Anti-Drug Coalition and work to promote recovery every chance we get. Additionally, we engage in presentations for organizations when asked.”

The program now has three courts: two of them in Lincoln County and felony courts in Lawrence and Maury counties. Recovery court proves to be life-changing.

“We have gained more community support as people witness the lives changed by recovery court. People have gotten their lives back. Families have been reunited. Crime has been reduced. Our program is small. We only have about 25 or so participants at a time, and the program can take up to a year or more, so that affects the impact some. But, even if just one life or family is saved, the benefit is immeasurable,” said Myrick.

It has infused hope.

“I also do criminal court, civil court, and juvenile court. Recovery court is the most rewarding aspect of my work. Another judge once told me he would have quit long ago if it were not for recovery court, which gave him hope,” said Myrick. “Few things are more rewarding than to see a person completely turn their life around, getting their children back, starting careers, opening businesses, and going on to help and counsel others fighting addiction. The last I checked, recovery courts enjoy a 70% non-recidivism rate of their graduates.” The local rate, according to Patterson, is approximately 85%.

The Lincoln County Courthouse, once a revolving door for addiction-related offenses, is a threshold of hope. Through the recovery court, its partners, and the community’s support, a network of resources now extends far beyond the courtroom walls. The program chips away with each graduate at the stigma surrounding addiction, replacing despair with possibility. As former defendants become mentors and advocates, Lincoln County Recovery Court is reshaping the community’s approach to addiction, one person at a time. GN