WHILE SOME students experience a school year filled with the excitement of homecoming events, spirited sports competitions, and bustling after-school projects, a different reality their siblings, and the tragic loss of a classmate leaves unanswered questions.

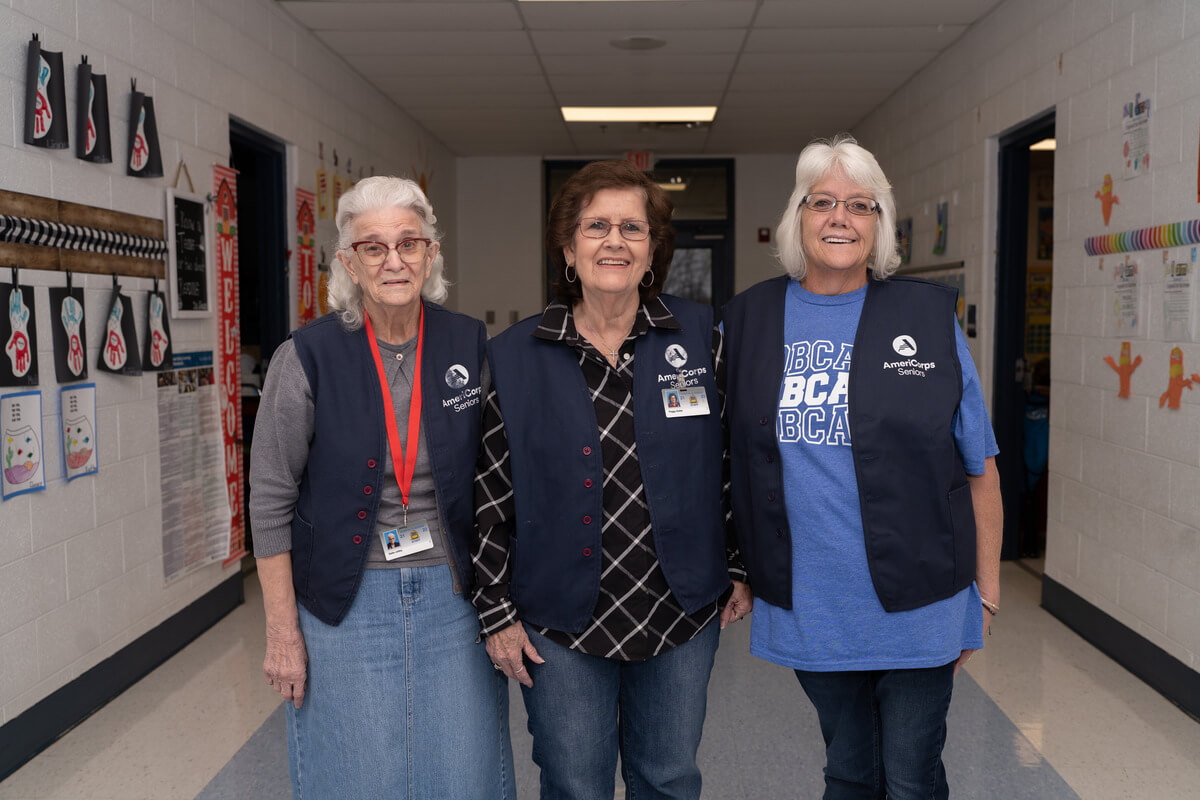

Claudia Styles, the federal programs supervisor of Fayetteville City Schools (FCS), recognized the immediate need to address the social and emotional well-being of FCS students and their families. To bridge this gap, she secured a transformative three-year grant to place a social worker in each of the district’s schools; Ralph Askins, Fayetteville Middle, and Fayetteville High Schools.

Styles explained, “I could hear these needs, but I didn’t know how to address them with our families. I love the fact that these ladies are trained professionals. They understand the home environment and how to work with families experiencing hardships that cannot always be addressed in the school setting.”

In its inaugural year, the program has yielded immediate and positive changes. Styles said, “All you have to do is ask any person in the school, and they will tell you the difference — that it’s the missing link. We missed having that person to make the needed connection between home and school.”

The social workers leading this transformative effort are Jennifer Taylor, serving Ralph Askins; E’Sheia Hicks, based at Fayetteville Middle School; and Candace Poliquin, working with Fayetteville High School.

In an increasingly digital world that often isolates individuals, this team wasted no time implementing programs that encourage social interaction and sharing. For elementary students, morning meetings in a circle provide a vital opportunity for personal connection. Taylor elaborated, “It’s about 10 to 15 minutes where they sit in a circle, making eye contact and having conversations, something they often lack in today’s digital world. They’re used to texting and interacting in other ways with little one-on-one eye contact and conversation. And so that’s what the circle does; it creates community.”

At the middle school, Hicks invites individual students to a time of conversation over lunch, her table talk program. “We sit at the table and just talk, and they really like that.”

Poliquin expanded on her approach at the high school level, stating, “We’re doing weekly meetings. Students discuss a theme, share their feelings privately on a Google Doc, set goals, and reflect on progress, making them more goal-oriented.”

The social workers support parents, too. Hearing and connecting their needs with resources improves relationships and bridges the gap between home and school, especially in trying situations.

The grant facilitates a safer and healthier environment for students. As conversation improves social skills and programs educate about emotions, there is progress in managing life at home and school.

The social workers are a resource for students facing bullying. Hicks said, “It’s safer knowing there’s somebody to [talk] to at the school if I’m in trouble, if something’s wrong, or [if] somebody’s bothering me.”

The support these social workers provide is often absent in students’ home lives. The responsibilities they bear outside of school can clash with the structured learning environment. Poliquin highlighted the importance of social-emotional learning to support students who are used to being the parents at home.

Taylor stressed the value of social-emotional learning in elementary education, stating, “Children often have a hard time identifying their feelings and emotions. I believe that is where social-emotional learning comes in. If we can teach children to label and identify their emotions, then we are better equipping them with the language they need to express themselves in a more positive way. Teaching children to talk about their emotions also allows us to teach them how to have empathy. When children have empathy, they can see the world from another person’s perspective and develop compassion for others. It is a vital component of social-emotional learning and can help students build relationships, regulate emotions, communicate better, and resolve conflict.”

Though still in its early stages, this program shows great promise. In a world increasingly fraught with challenges, the presence of dedicated school social workers can make a profound difference, fostering a stronger and more emotionally resilient community.

Hicks sees a positive future and said, “It’s going to be good to see in the three years [of the program] the difference it will make by the time today’s sixth, seventh, eighth, and ninth graders get to high school.”

This initiative is a potent reminder that investing in students’ emotional well-being yields benefits far beyond the classroom. By bridging gaps, nurturing connections, and offering vital support, these social workers shape a brighter future for everyone. GN