IT’S A different world today. With a little spit or a swab of your cheek, a DNA test kit will promise to return details of your ancestors’ country of origin, inform you of your health issues, and give you information on personal traits. But missing from these results are your great-great-grandparents’ stories, treasured heirlooms, and information about their life and times. However, the kits spark more research and a second look at your family tree.

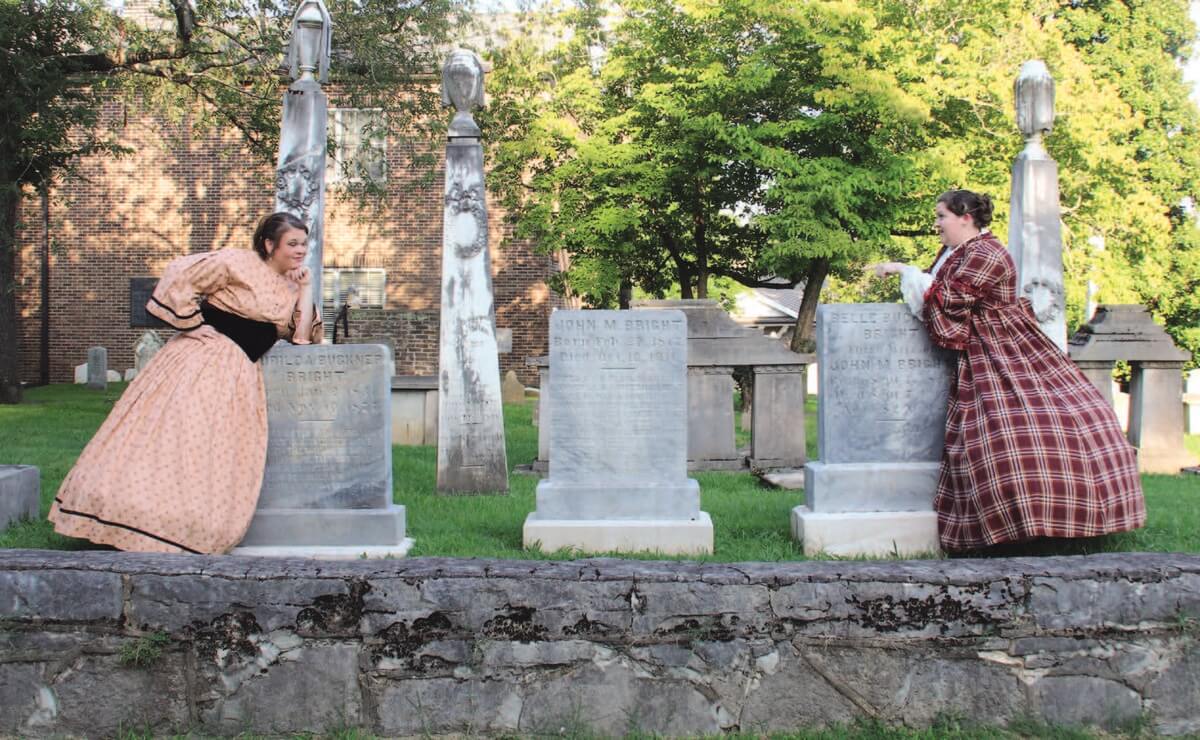

Death and burial records are essential in the genealogist’s toolbox. Family cemeteries on private property were common in early settlements. Many have been lost to an overgrowth of trees and vegetation, and the graves and stories of those laid to rest there have gone silent.

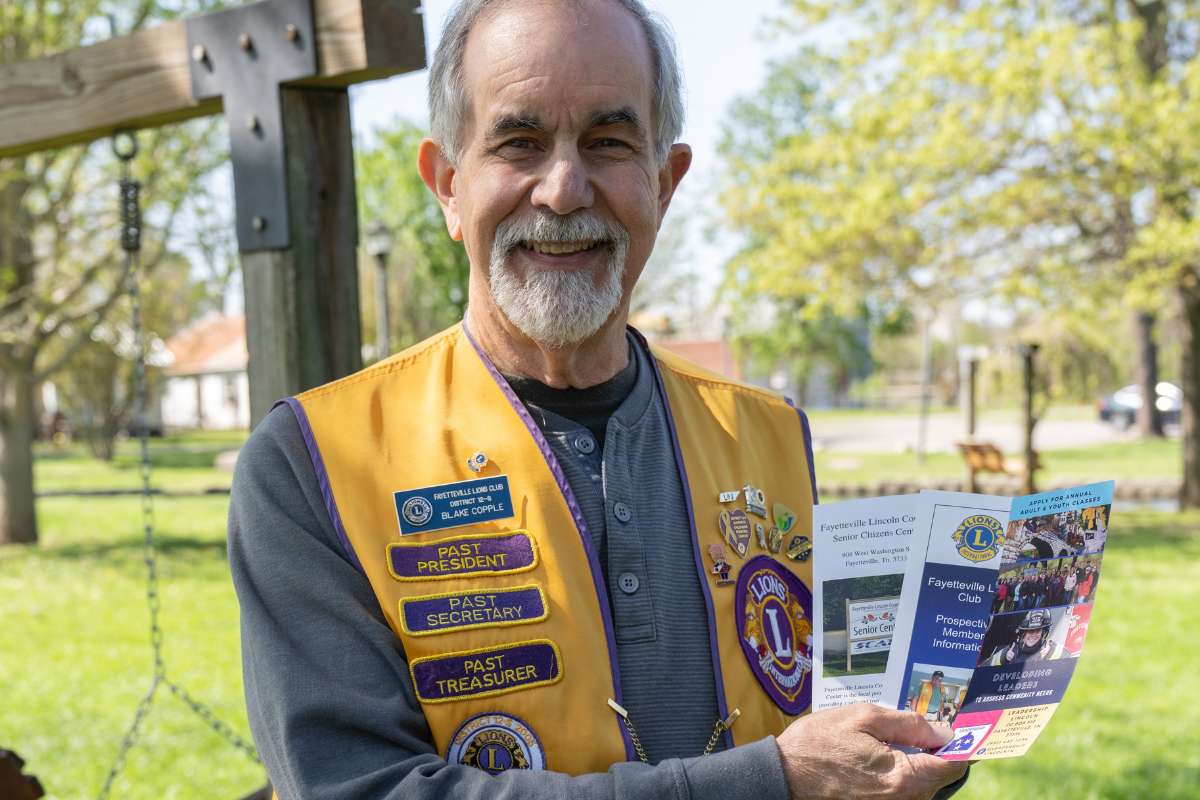

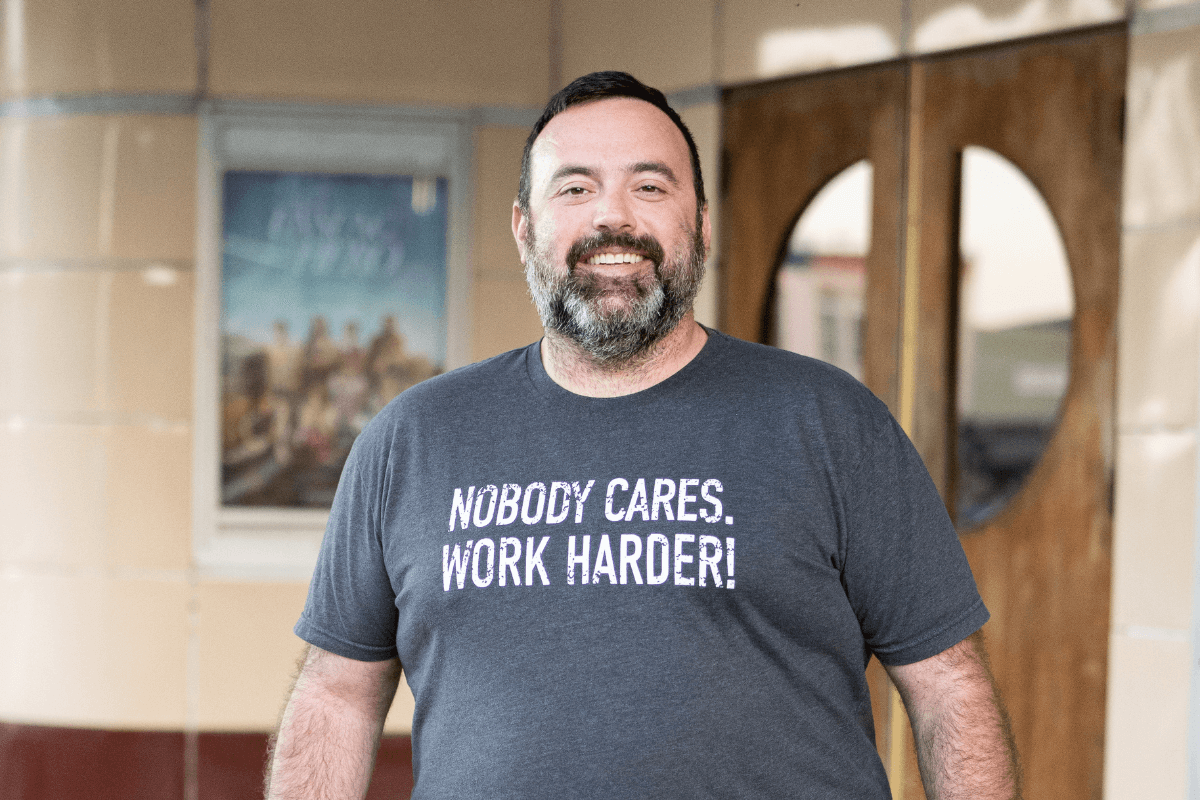

You might say Wayne Owens and Jim Steelman are a “CSI” team — cemetery site investigators. Friends and former classmates, the duo is passionate about locating old cemeteries and making them accessible in person and online to those searching for the details of their past.

Over the past 10 years, they have visited over 250 cemeteries, excavated many lost grave markers, and taken 7,000 photos. They have established 2,400 memorials, added 4,300 photos, and provided 471 photos in response to requests on findagrave.com.

Determining the most specific location of a cemetery is the first step, then identifying the property owner and obtaining permission to look for the cemetery.

Many landowners have no idea a cemetery is within the boundaries of their property, and some don’t know the cemetery is not theirs. Tennessee law excludes burial grounds from ownership and requires the landowner to allow public access to them.

A quest for unearthing a cemetery often becomes an appreciation for today’s modern conveniences and medical advancements.

Steelman said, “At the Crawford Cemetery on March Mill Road are markers for four children in one family who died within a month and a half of each other in the late 1800s. In those days, there were epidemics, scarlet fever, and things that would come and wipe a family out. What really got me was the stones. They had engraved hearts, and the hearts were upside down.”

Life in those times was hard and was sustained by land, water, and other natural resources.

We go by some of these cemeteries, and I look around for old house walls, and there’s a small family cemetery, and I wonder how in the world a family made a living on this property. It’s rough; it’s hilly. We’re talking about some tough people here that were the forebears of our Lincoln County population.”

Owens agrees. “We share a respect for the history and experiences of early residents here, especially those who were not prominent or in the public eye. Most lived in the hills and hollows off the beaten track.”

Long, hard work preserves history for many generations to come.

“We’re often asked why we do it. Some have called us crazy. Some are uncomfortable in cemeteries, especially doing excavations to raise buried markers. But the great majority appreciate what we’re doing and help by telling us cemetery locations not widely known,” said Steelman.

The cemetery site investigators leave things better than they found them, clearing the way for the stones to stand again and witness lives lived long ago that paved the way to the better lives we enjoy today. GN