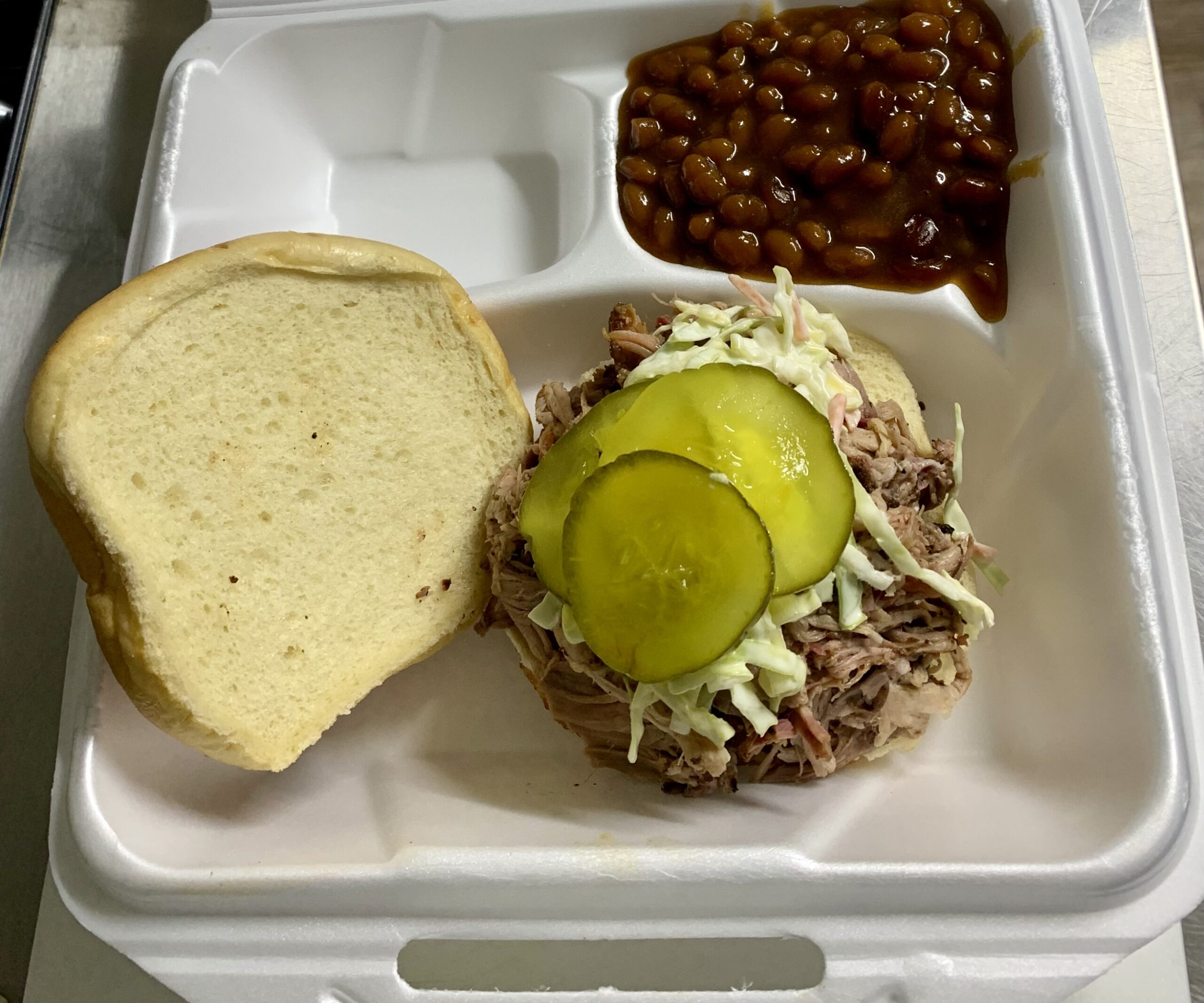

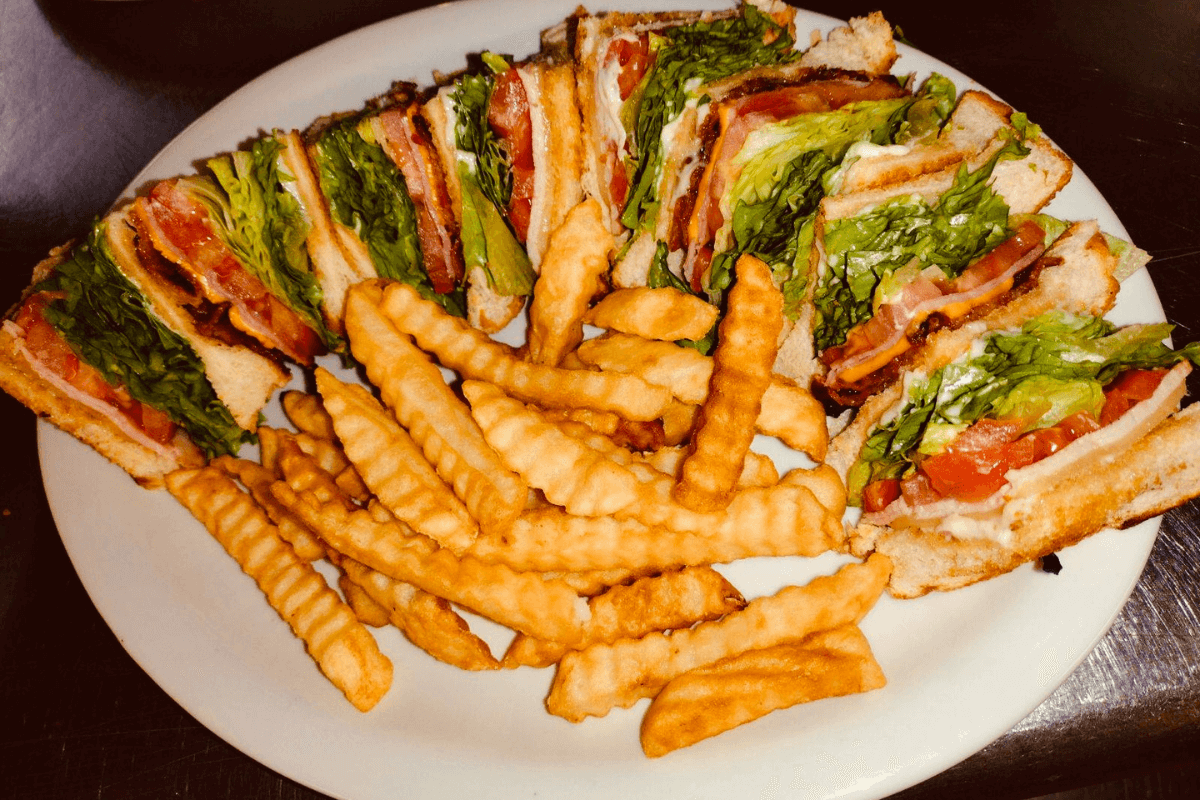

THE NATIONAL anthem is finished. Spectators return their caps to their heads and settle into their seats—some on the outside ring, some in box seats, and others in the stands. The red, white, and blue buntings wave silently in the late summer breeze, and the sweet aroma of funnel cakes comingles with popcorn’s salty scent from the nearby midway.

The bugle announces the call for the first day’s class.

It’s back!

“Watch the top of the stretch, ladies and gentlemen… The starting gate heads this way… and heeeerrrrrrrrre they come! Mike Moss pulls away, closes his gate, and going to the front is …” the voice of the races for so many years, Charlie Therrell.

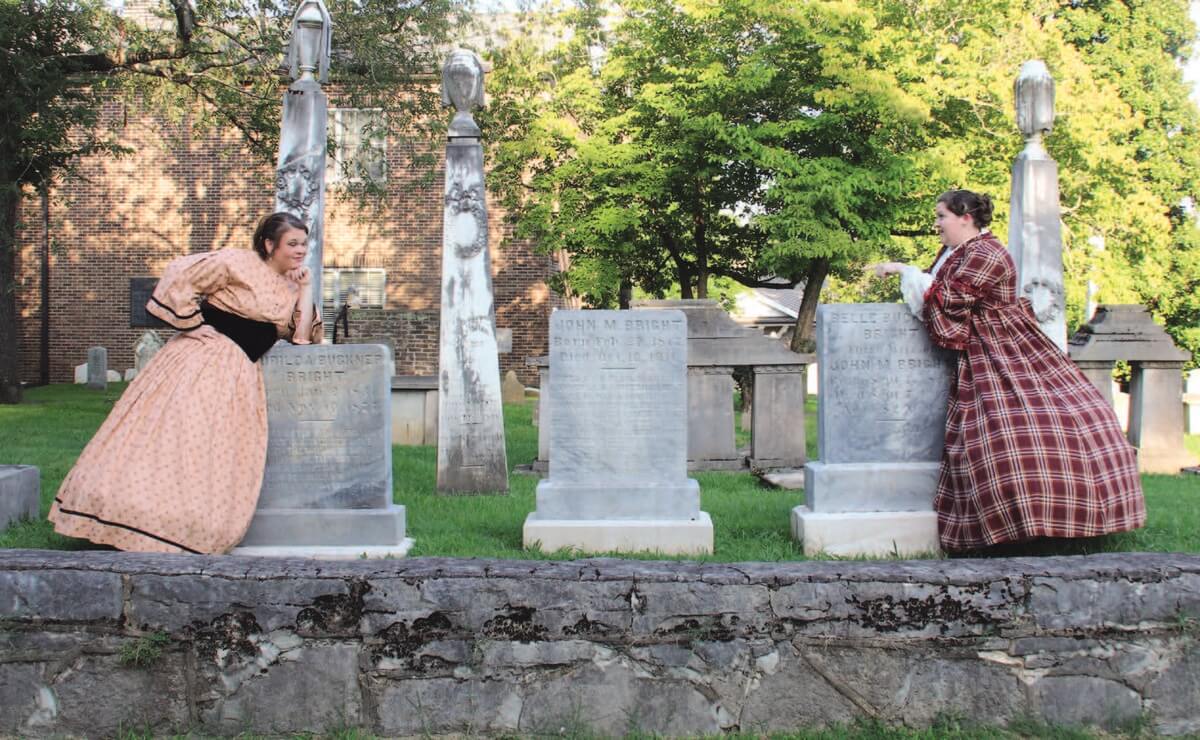

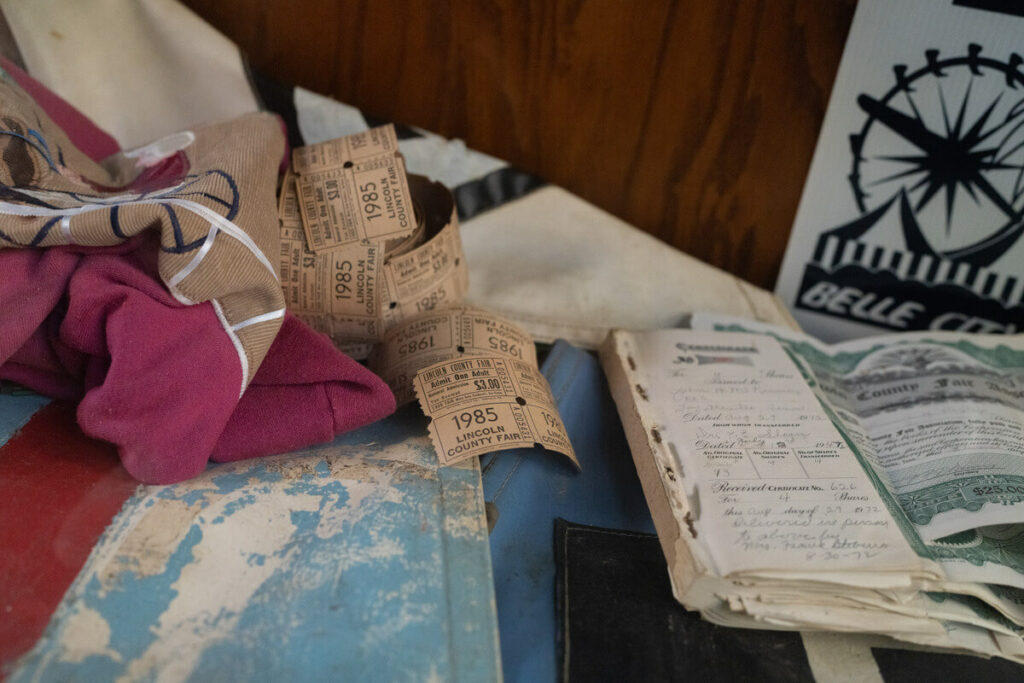

Each year, harness racing makes its sole fair appearance in Tennessee at the Lincoln County Fairgrounds, a tradition dating back to 1904. The only years from which it was absent were twice during World War II and the COVID pandemic in 2020.

According to tennesseeencyclopedia.net, as the 19th century drew to a close, Tennessee experienced a shift in sporting interests, with trotters edging out thoroughbreds. Harness racing continued to enjoy support in rural communities, with Maury, Giles, Rutherford, and Marshall being the top breeding counties.

How has Fayetteville become the sole harness racing track on the fair circuit, and what is its appeal?

Names like James Ray Golden, Mike Moss, Jerry Harry, Mrs. Sarah Byrd Posey, Vera Stewart, and Charlie Therrell often resurface in the memories of locals with love for the sport.

Johnny Farmer, track, race, and barn superintendent of the Lincoln County Fairgrounds, said, “It’s hometown, you know?

Years ago, when I started out, Jerry Harry, Mrs. Sarah Byrd Posey, and Mrs. Vera Stewart were in it big, and they’ve passed now, and none of their families got back in it. Mrs. Stewart never drove, but Mrs. Posey drove a few times. Mrs. Stewart and her husband, J.A. Stewart Jr., were big time in his days. He left and would be gone all summer racing. And after he passed, she kept horses and sent them up to Kentucky to be trained by Van Carter, who also trained Ms. Posey’s horses.”

It was a family tradition for James Ray Golden, track superintendent, as far back as 1968. His son, Ricky Howell, said, “I remember Pops racing back as far as 1968 when I was 8. He trained and drove until he had a stroke.”

Christi Howell recalled how important it was to her fatherin- law to share the harness racing with his family.

“James Ray wanted the kids to see him race and be with the horses. He would come to get Andrew on Monday mornings and take him to visit the horses. They’d ride in the pace car, and our kids would go down and help present the trophy blankets when he won. It was a big deal for our family. We would take the kids out of school on Friday afternoon. Pops would make sure he could be in a race on Friday afternoon, and we would take the kids out of school at lunch and go down and watch races all Friday afternoon. And it was a really big deal to our family while he was in it. There’s a lot here who are trying to hold on to it, like Billy Miles, Randy and Rocky Cowley, and Dale Gentry, but there are no new families getting into it,” she said.

The central location of the track between Kentucky and Mississippi may be key to its ongoing attraction, especially to the Mississippi racers. It also offers a handy spot for training between Kentucky races.

Ricky said, “The Mississippi crew races in Kentucky all summer and are heading home, stopping on their way in Lincoln County, but there’s not as many of them as there used to be.”

The financial payout is not the draw; the payout is in relationships and a time to reconnect.

Christi said, “The Mississippi drivers made friends here with the Lincoln County drivers—like a big family—visiting and racing a little bit. They know there’s not a lot of money here.”

Aunt Jo, Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, Miss Fountain Inn, and Yankee Ranger were a few of Golden’s horses, their names spurring their other memories.

Memories and relationships are two things still produced by harness racing at the Lincoln County Fair. GN