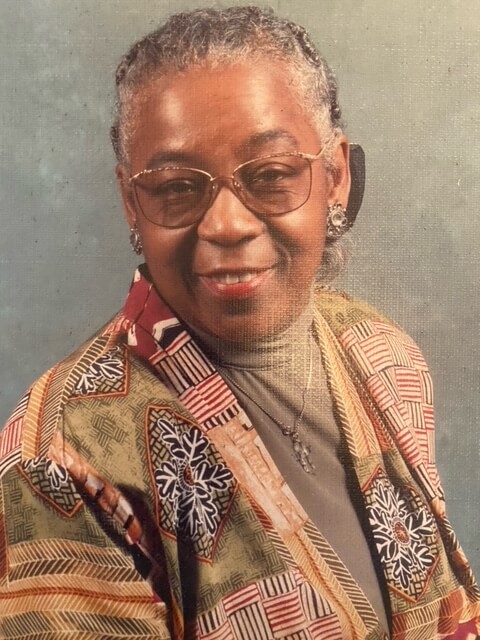

AT SHELBYVILLE Mayor Eugene Ray’s funeral, Fredia Lusk saw evidence of a well-lived life. As Shelbyville’s first and only African American mayor to date, Ray’s legacy was more than a statistic. Lusk knew that Ray’s success and the success of other African Americans in Bedford County were possible due to the lives of those that came before them. She believes the success of current and future generations depends upon recalling the lives that have gone before, and an idea to preserve it was born.

She said, “I was sitting there thinking that history is so important for our children and grandchildren, and they need to have a record of the accomplishments we made in our lifetime. As a retired educator, I was concerned about our story being lost or remembered. This book is my effort to preserve our accomplishments as an African American community.”

Lusk continued, “They need to know the struggles we overcame and the obstacles we faced just surviving as black people or African Americans living in a different country. The books I’d found about Bedford County had no inclusion about blacks even living here or being here. So that was my desire to record history, to show that we have had successful individuals in our culture rise above heartache and setbacks.”

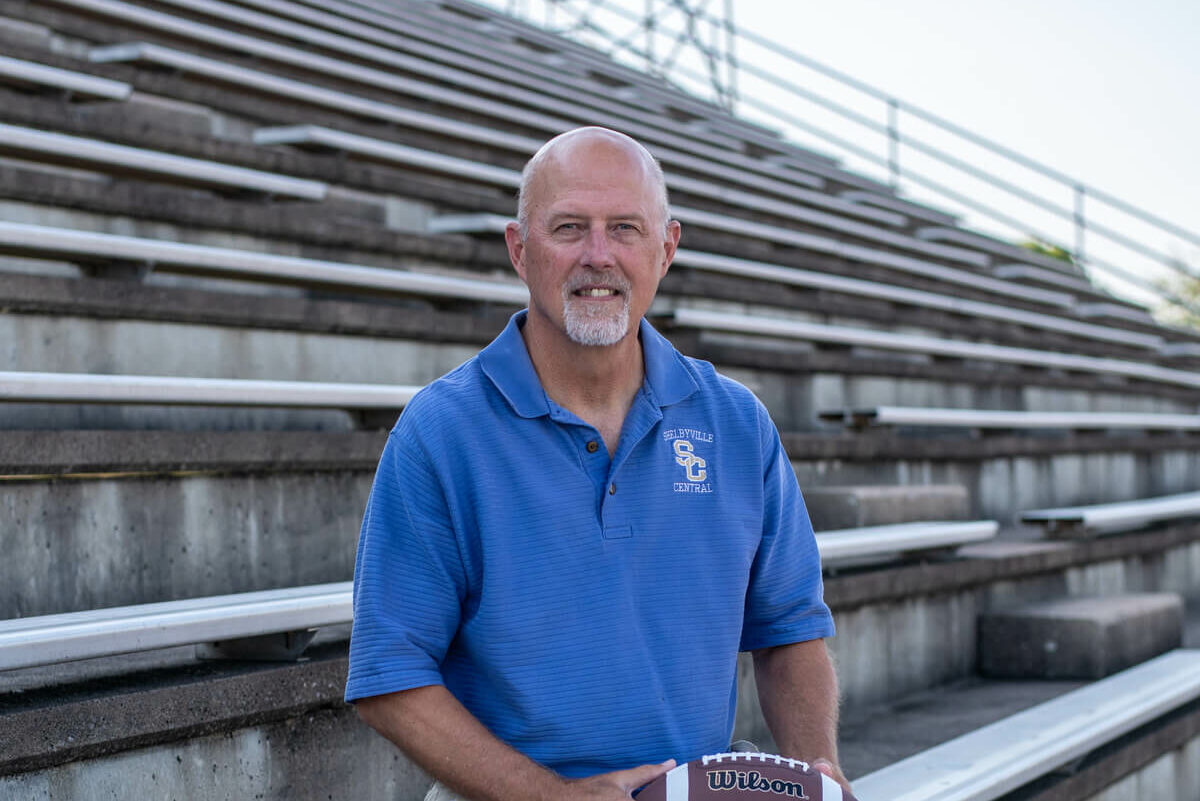

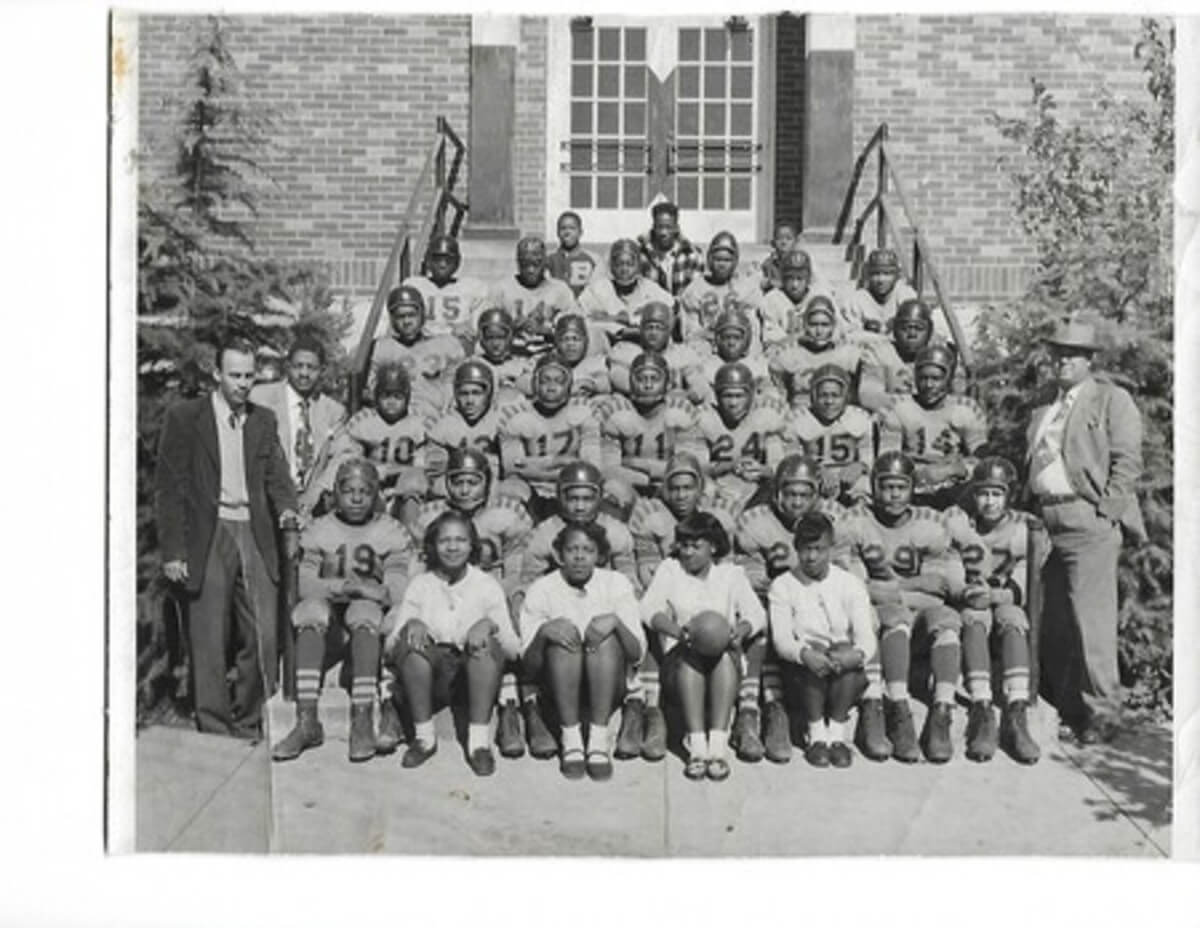

It’s a history steeped in perseverance, grit, and a deep desire to better the lives of a population divided for a time by the boundary lines of race. Black communities were self-sufficient and prosperous, with a diverse population working to serve one another through their businesses, professions, schools, and churches.

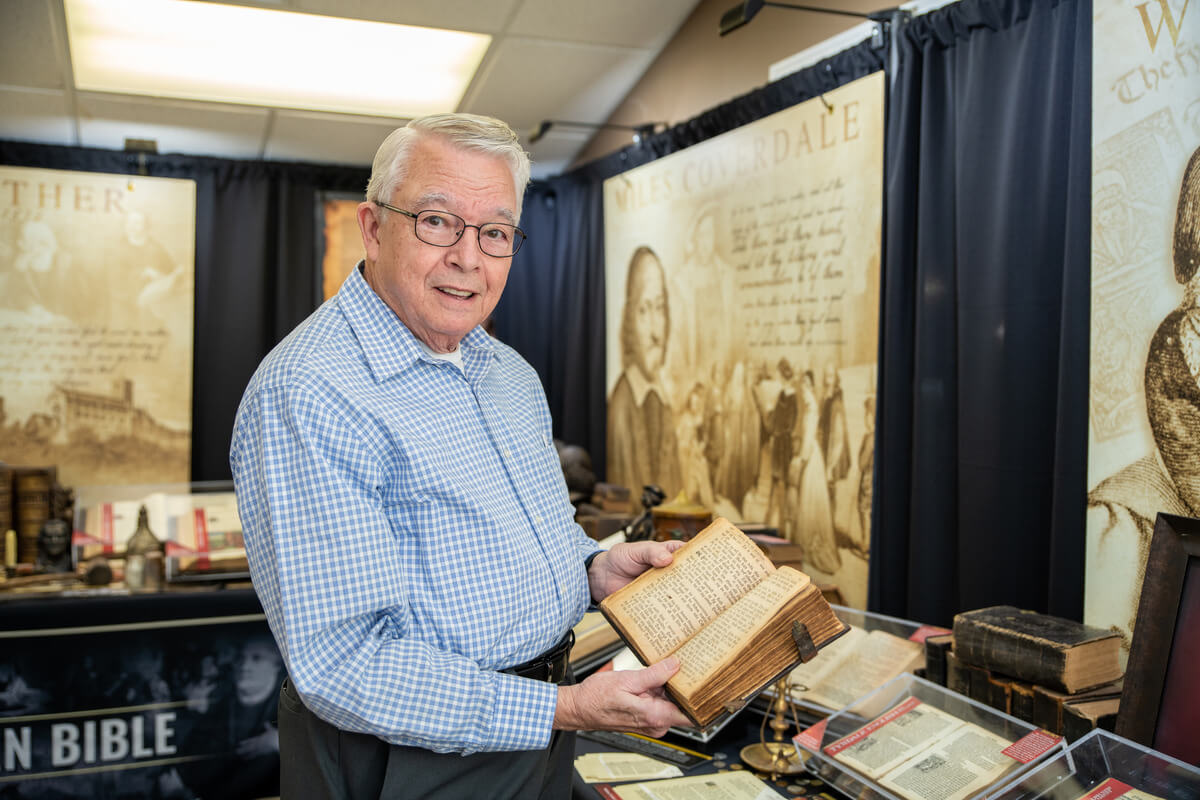

“African Americans Living in Bedford County from 1820 to 2020” will include general Bedford County history, recent historical marker information, education, athletics, business, government, military, music and arts, and religion. And although slavery had been abolished years earlier, the era covered in the book begins with slave ownership in Bedford County still on record.

“There were slaves in Bedford County in the 1820s; I’ve documented that during my research that began in 2019. In 1819, there were 125 slaves in our county and only a few landowners. There were 83 free black people living in our county, and this is from the Bedford County Archives. The more I researched, the sadder I became, and the more determined I became to tell our story,” said Lusk.

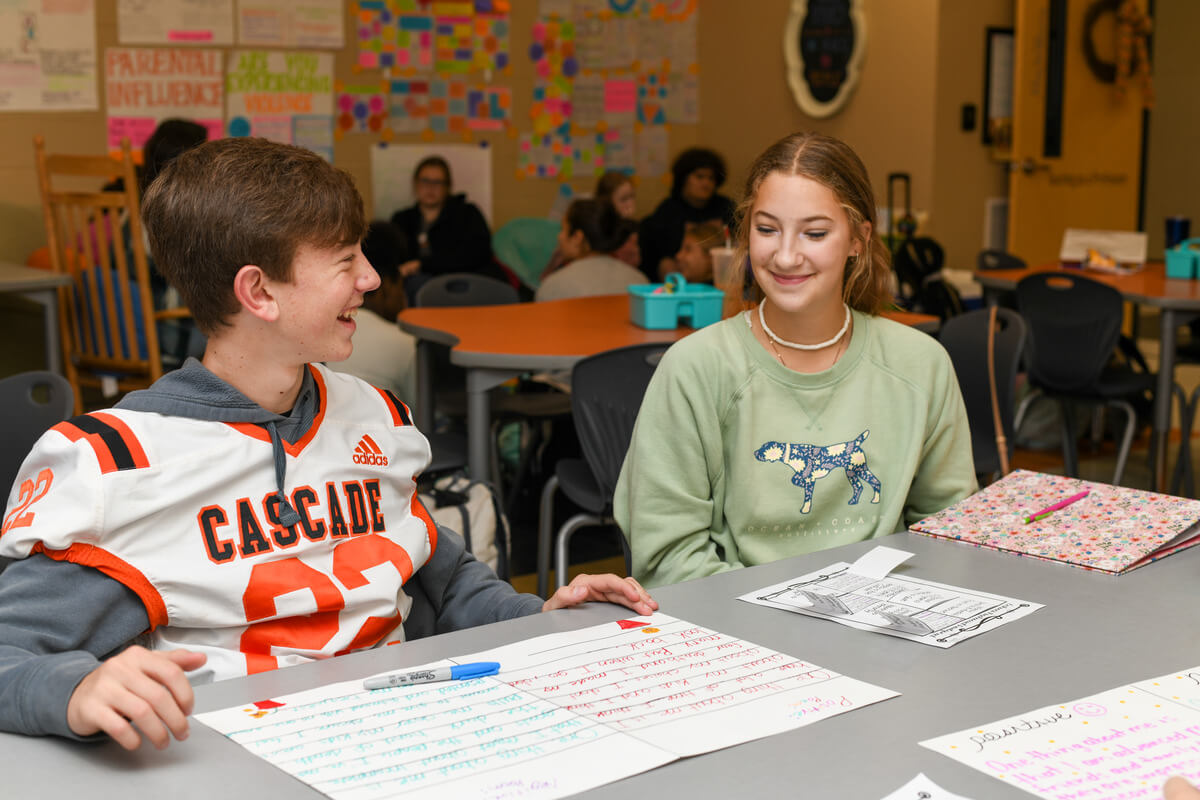

The hope afforded by education is a bright thread in the tapestry of the history of the black Bedford County community.

Lusk said, “I’m finding in all my research that families fought for their children to be educated. Even during slavery, they wanted to be educated, but the white masters forbid them from learning to read or write.”

A vibrant community and culture immerge from Lusk’s research. Business owners, professional musicians, professional athletes, and everyday, hardworking people lived and worked side by side, constantly striving to improve their way of life. Personal interviews with living residents enrich the book, too.

“The three-year research project has been challenging but interesting. I cherish the oral interviews with Marilyn Massengale, J.V. Abernathy, and my mother, Gladys Flack,” she said.

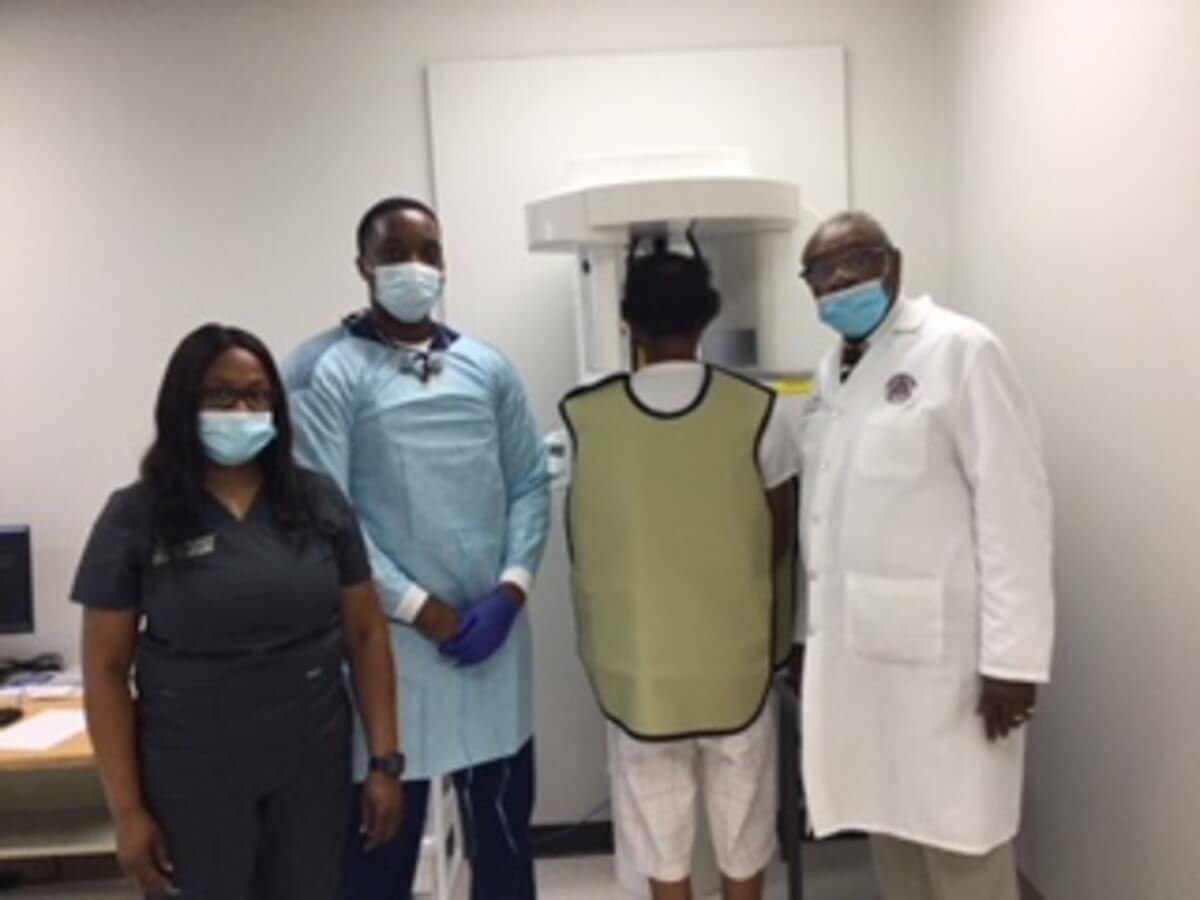

Lusk’s work is a labor of love, and proceeds from the sale of the book will benefit the Community Clinic of Shelbyville & Bedford County and The Rosenwald Center. GN