ON CHRISTMAS Day, in the early ’70s, a truck driver drops coins into a truck stop pay phone while piling the rest of his change on the ledge below it. He’s anxious to hear his wife’s and children’s voices, wishing he was sitting with his son in his lap, laughing at his brother-in-law’s bad jokes, and eating the red velvet cake his mama makes every year. Closing his eyes, he sees the glow of multicolored lights on flocked branches and the packages piled below and spilling out in every direction.

A hundred miles away, lights blink, not on a Christmas tree, but on a board of circuits. She’s surrounded by chatter from those around her and in her headset. Her husband is home with their daughter, playing with toys from Santa and eating leftovers from an early family dinner.

Plugging the red cord into the board, she says, “Number 99, how can I help you?” jolting him back to the clanking dishes and voices of strangers around him, reminding him again how far he is from home.

He asks to be connected to his home phone and waits as Number 99 plugs the black cord into a different circuit and dials the number for him. As soon as she’s sure they’re connected, she stamps the call’s start time on a ticket and watches the clock and the call, ready to request more payment to continue. As each coin dropped, its tone told her when the correct amount had been deposited. She notes the end of the call on her ticket and drops it into the slot on the board before her, simultaneously plugging into the next call.

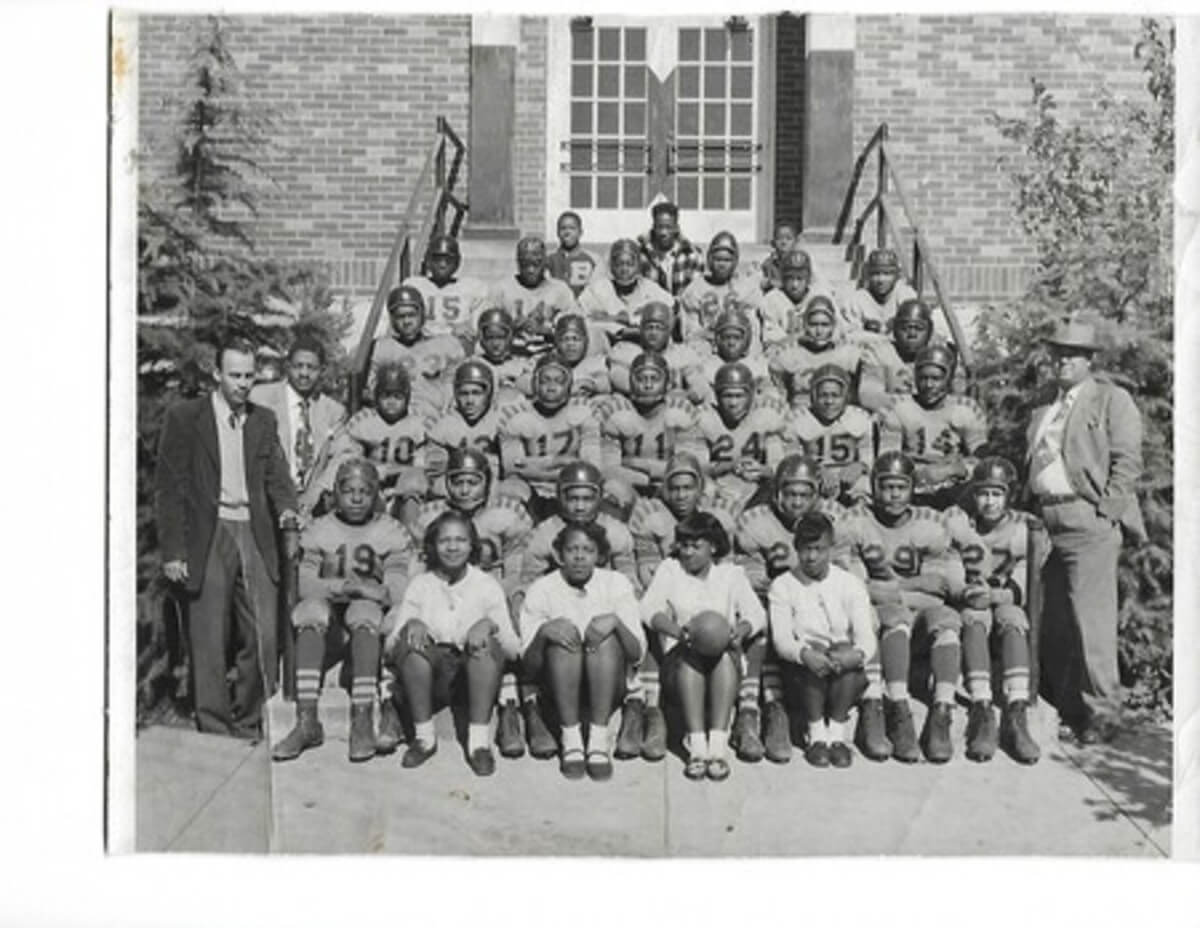

Before cell phones and landlines with the ability to direct-dial long-distance calls, hundreds of thousands of men and women handled walls of circuit boards ready to assist person-to-person, collect, long-distance, and toll calls. It was the voice of the telephone company, and it was a career that put area high school graduates immediately to work in jobs with outstanding benefits. A commitment to customer service and a solid work ethic were its main requirements, both of which could be very challenging in extreme circumstances.

Calls like these were answered in the old South Central Bell office at the intersection of Jefferson and McGrew Streets in Shelbyville, just off the public square. Numerable Shelbyville residents and those from other communities found work with the company, moving from operators to business departments in nearby cities once the switchboards were phased out by updated technology. Working side by side and carpooling united these operators for life.

In the days of the switchboard, posting the schedule (or tours) was the most highly anticipated event. Seniority ensured better shifts, and it wasn’t uncommon to work split shifts in Shelbyville’s 24/7 location.

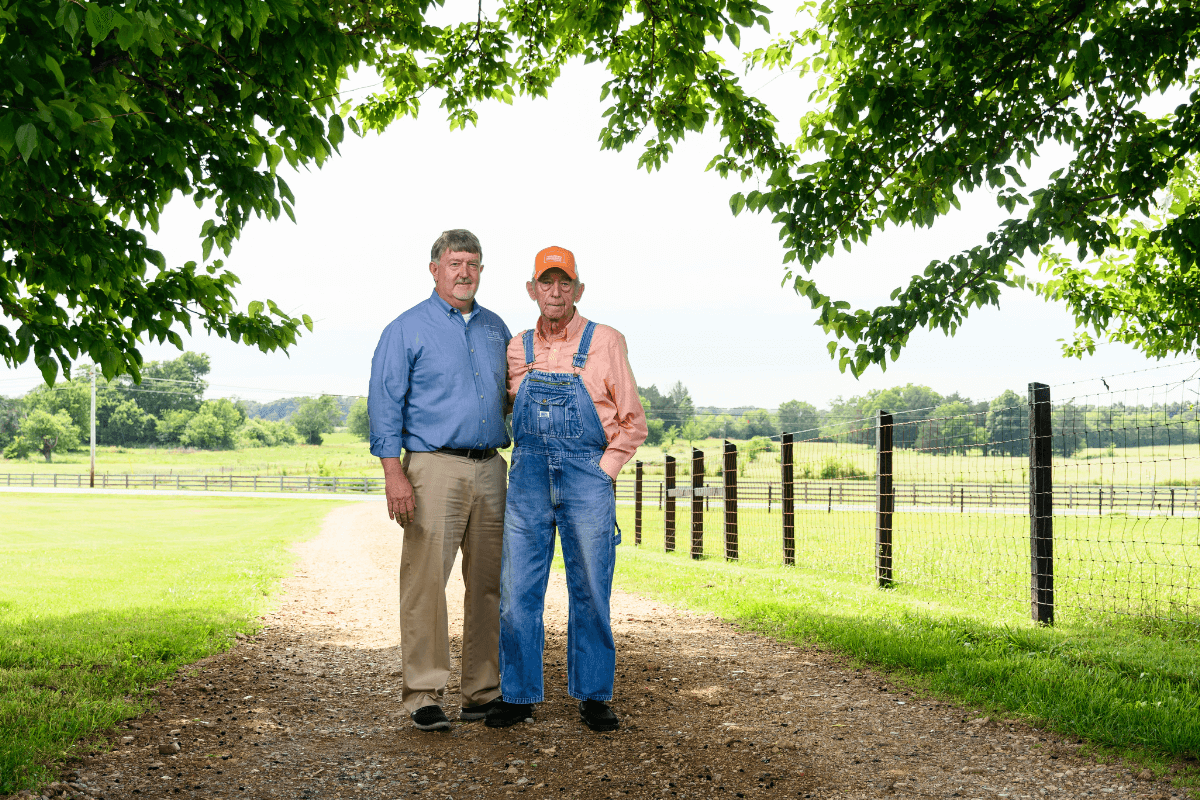

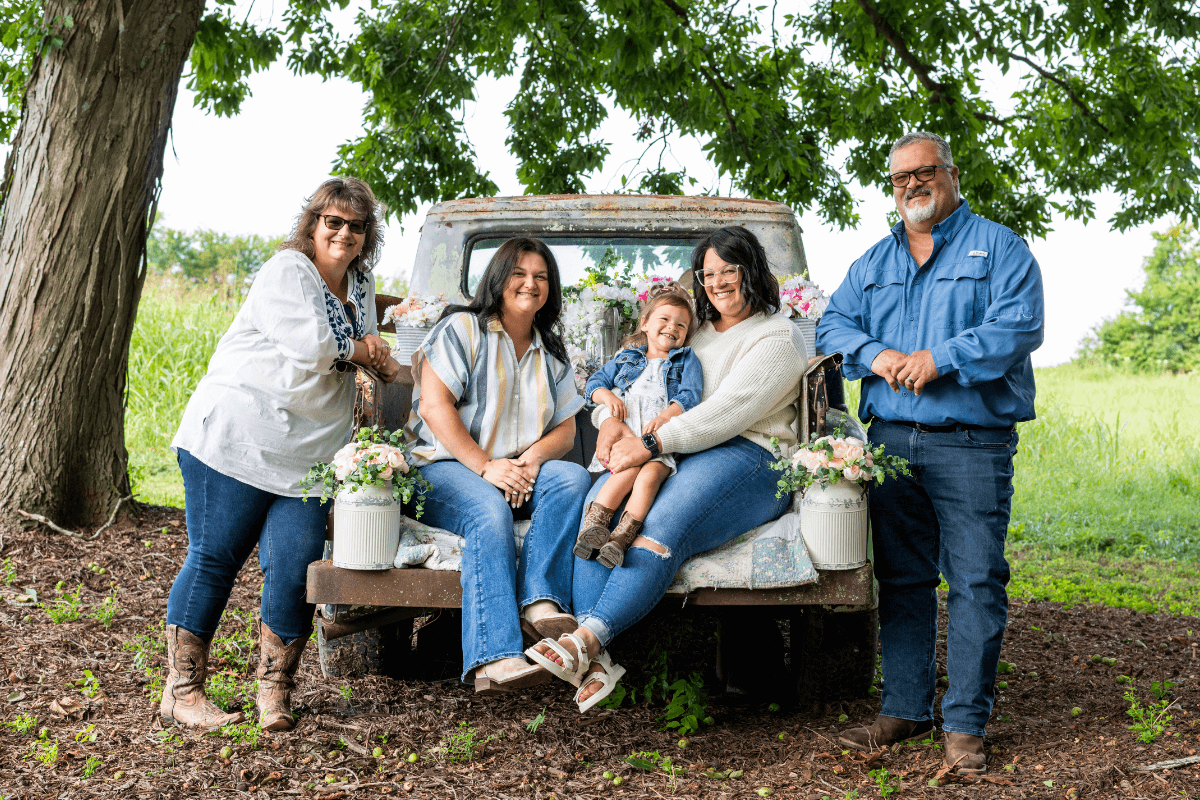

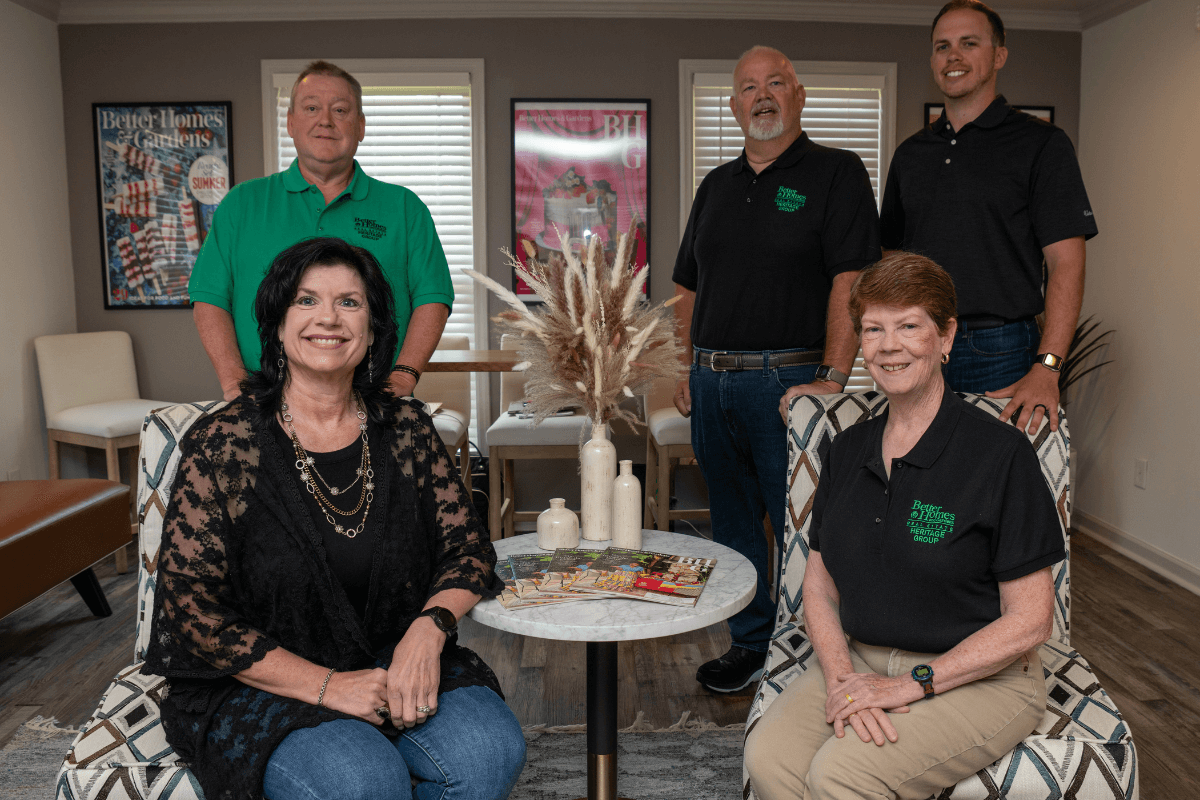

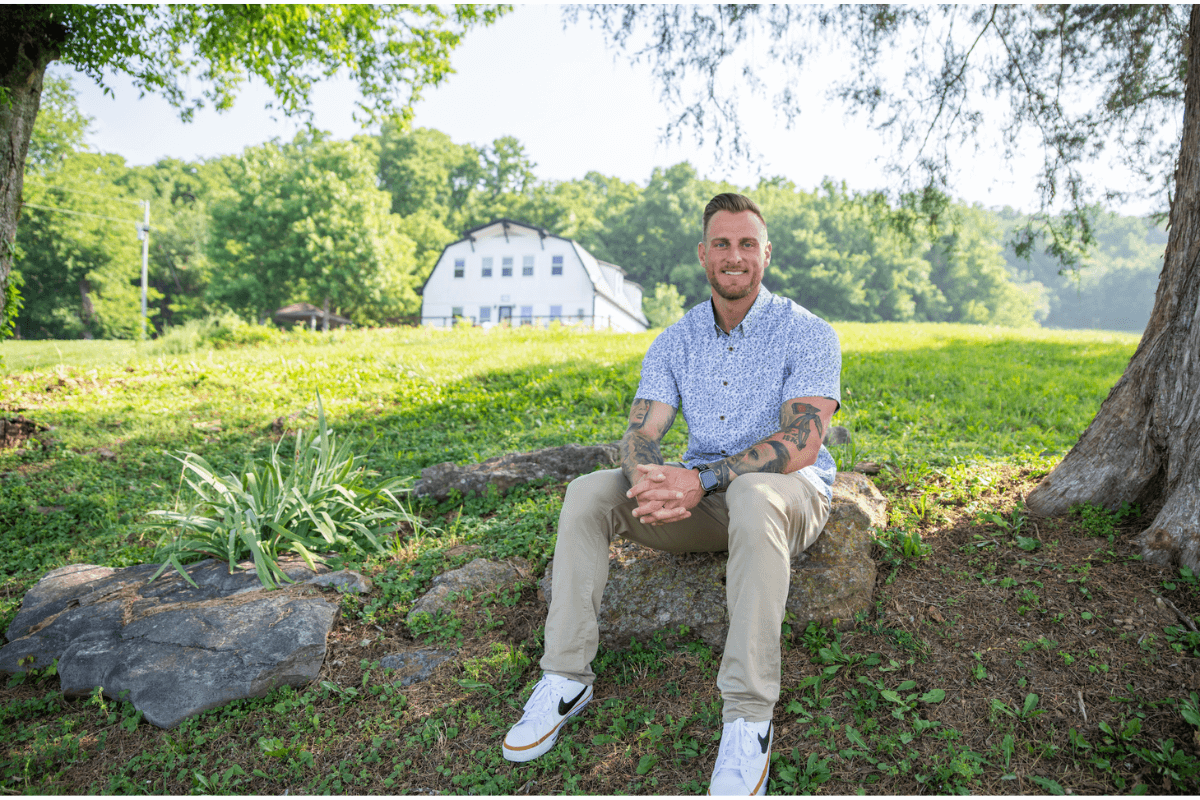

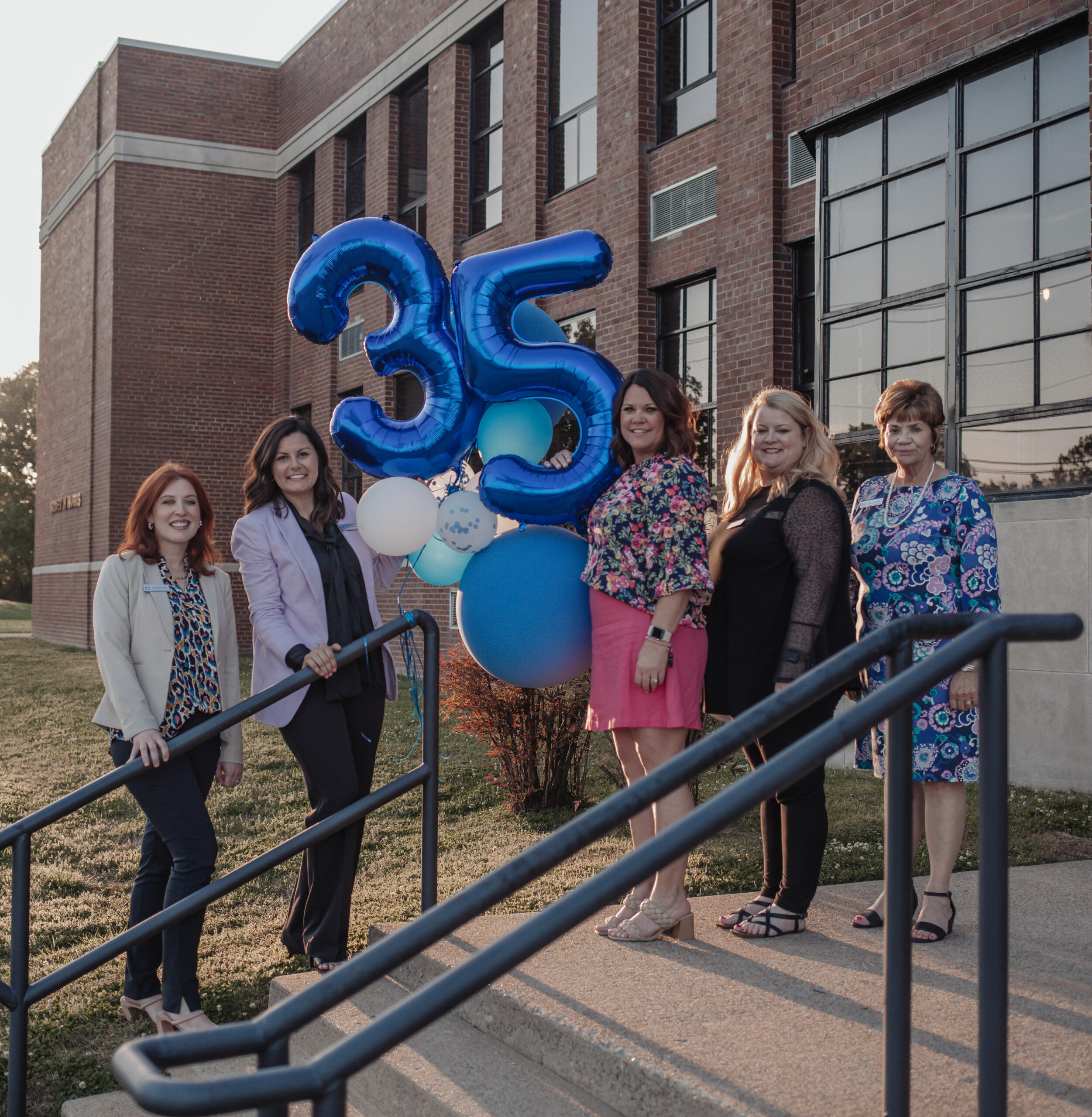

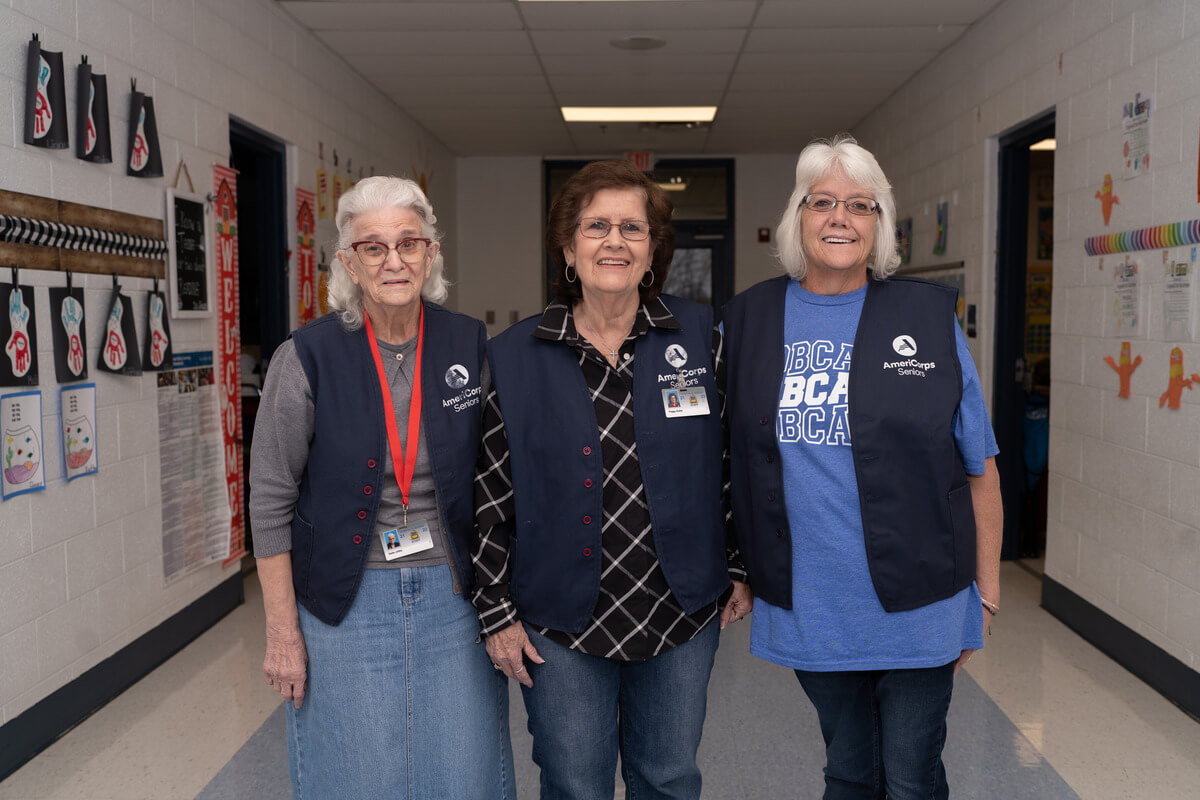

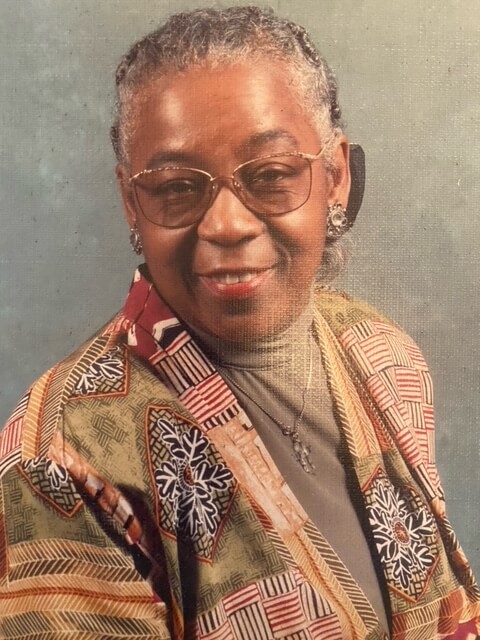

Linda Baucom Jones, Judy Neeley Sawyer, Linda Neeley Wells, Zena Norris Phillips, and Frances Hill Baucom are a small part of the Shelbyville group that worked together and went on to retire from the telephone company.

“I will never forget Daddy taking me to apply and our conversation with Robbie Raines. I went to work right after graduation,” said Phillips.

Jones, who started in 1970, recalls, “My first tour was 1:30-10 p.m. until I ‘graduated’ to a split 7-11 a.m./4- 7:30 p.m. shift. Those shifts took up your whole day and night. It was too bad if you had something planned unless you could get someone to swap with you. Calling out was not an option.”

Baucom agreed. “It was hard to keep up with the schedule. Sometimes we would have two or more people show up at the same time, but we always had Ms. Nelle to work it out and help us laugh through it.”

Laughter permeates the air when these ladies are together, no matter how long since they were last together.

When the Shelbyville office closed, they and other co-workers commuted, further sealing their bonds of friendship and family.

They all agree that commuting also brought hardship, especially during inclement weather.

Wells said, “We have driven in sleet, snow, and on solid sheets of ice. One day, we left Nashville at 3:30 in the afternoon, and it was 8:30 that evening when we finally arrived in Shelbyville. The six inches of ice we had one winter is the only time I recall we didn’t make it to Nashville to work.”

“We were like family, and I always enjoyed talking with customers, too,” Sawyer said.

Today, there’s not a pay phone in sight. Switchboards are found in museums, and the operators’ work can be seen only in old video footage and documentaries. But one thing survived; the friendships and memories are as strong and colorful as ever. GN