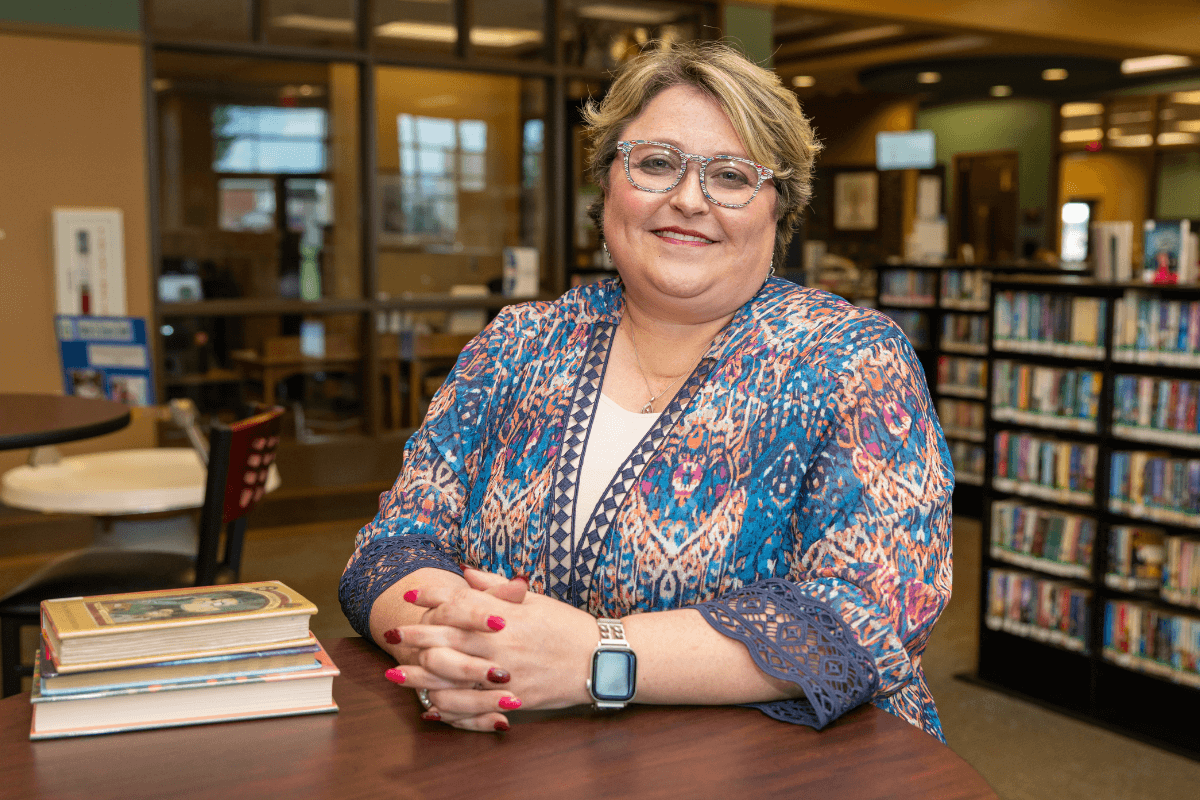

WHEN MELONIE Valleroy entered second grade, her mom started a job as a pharmacy technician at Middle Tennessee Pharmacy Services (MTPS), so Valleroy often spent time there after school and during summer breaks. When Valleroy became a freshman at Cascade High School, her mom was a supervisor, so she begged her to hire her as a pharmacy assistant, and one day, she did!

“My dad is a paramedic, so he works two to three 24-hour shifts each week. On those days, I spent the afternoons at the pharmacy with my mom, so I got to see firsthand how a pharmacy operates. If I was going to spend so much time there, I wanted to make some money, too. One day, during Christmas break, Mom texted me and asked if I wanted a job. I started that very day,” Valleroy recalled.

At MTPS, she often scanned the rows of orange prescription bottles strategically organized in alphabetical order. As a pharmacy assistant, she had emptied the trash cans, scoured the bathroom sinks, ordered supplies for the next week, and organized paperwork for incoming patients, but those bottles mesmerized her.

Many times, the front door of the pharmacy opened, and a familiar delivery driver would call out to her. He routinely asked the same question: “Are you going to be a pharmacist when you grow up?” She would always reply, “I’m not smart enough to be a pharmacist.”

Valleroy said, “To be honest, I didn’t think it would be possible for me to go to college, let alone earn my doctorate in pharmaceuticals. At that time, no one in my family had completed college right after high school, so I just assumed college wasn’t a possibility for me.”

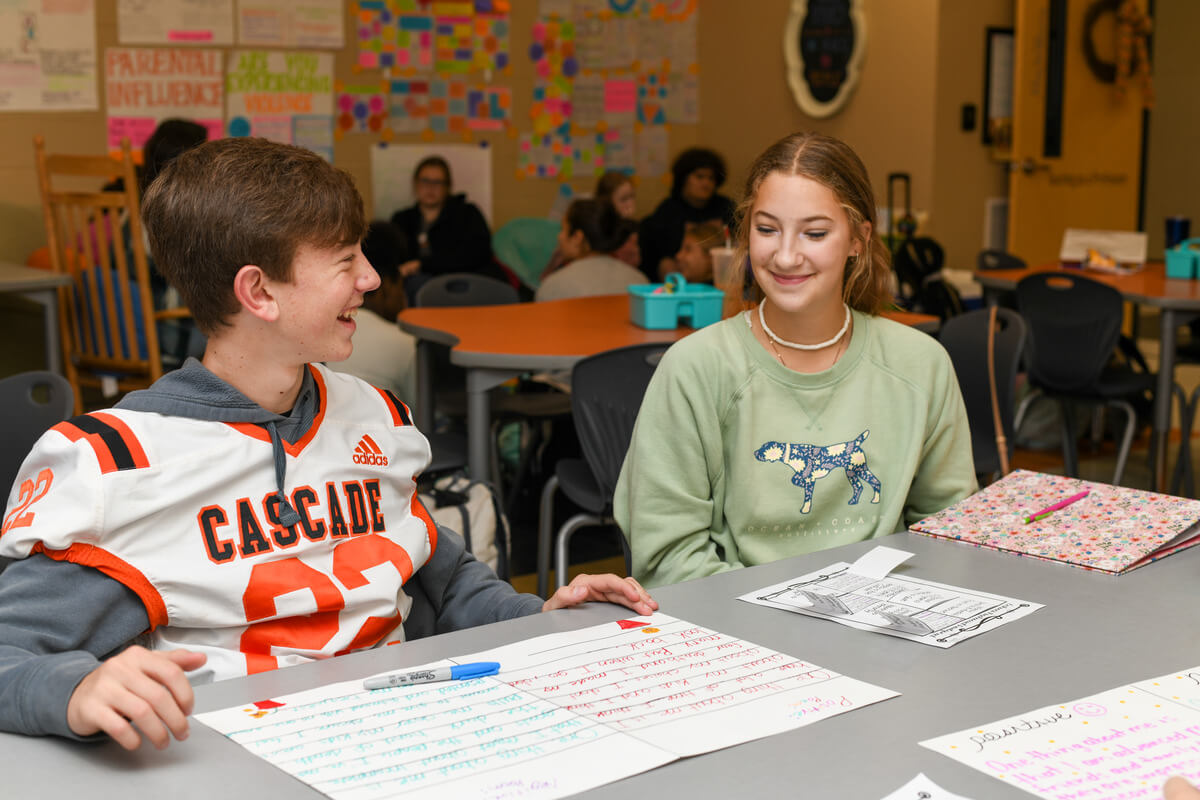

But when she became a junior, something inside her sparked to life. “I had to take chemistry in high school, and I fell in love with it. Scott Hrouda, the chemistry teacher at Cascade, prepared me and helped me excel in college chemistry courses. I was interested in going into the medical field. So one day, it was like a light bulb went off. I thought, ‘Why don’t I become a pharmacist?’ This field would allow me to continue learning chemistry and work in health care.”

Though she no longer worked for MTPS and instead worked for Kroger, she finally knew what her calling was. “After graduating high school, I went to Union University in Jackson, Tennessee. I wanted to attend a school where I could complete prerequisites and attend pharmacy school. Union has a six-year pharmacy track that includes two years of undergraduate prerequisites and four years of pharmacy school.”

During her first semester at Union, doctors diagnosed Valleroy with an autoimmune condition. She shared her experience with Student Pharmacists Magazine, and in July 2024, her article “Learning to Be a Patient While Learning to Be a Pharmacist” was published.

“Pharmacy school was a constant battle of trying to juggle what felt like more than I could handle, but thankfully, I was able to make it out the other side. While at Union, we were always told to begin with the end in mind. I tried to make that a priority.”

During times when doubts crept in, school assignments piled higher, and her physical health was uncertain, she clung to her faith and her ever-supportive family.

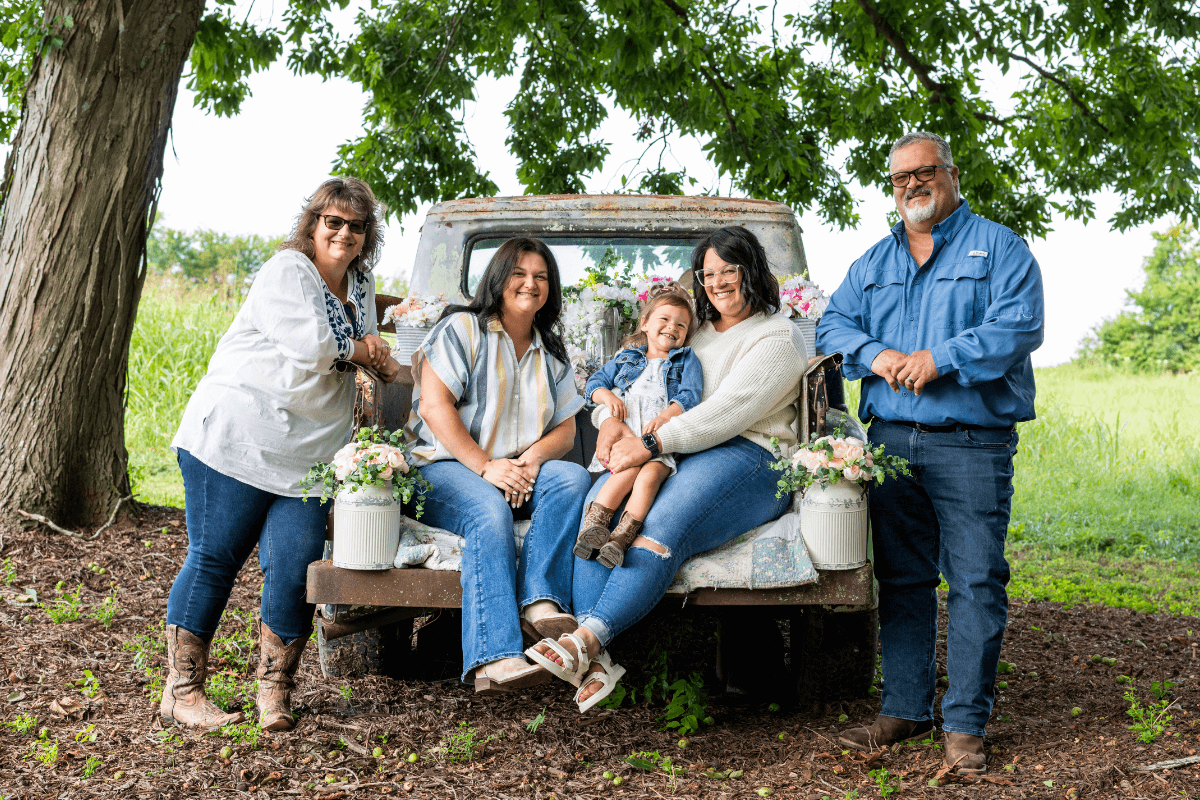

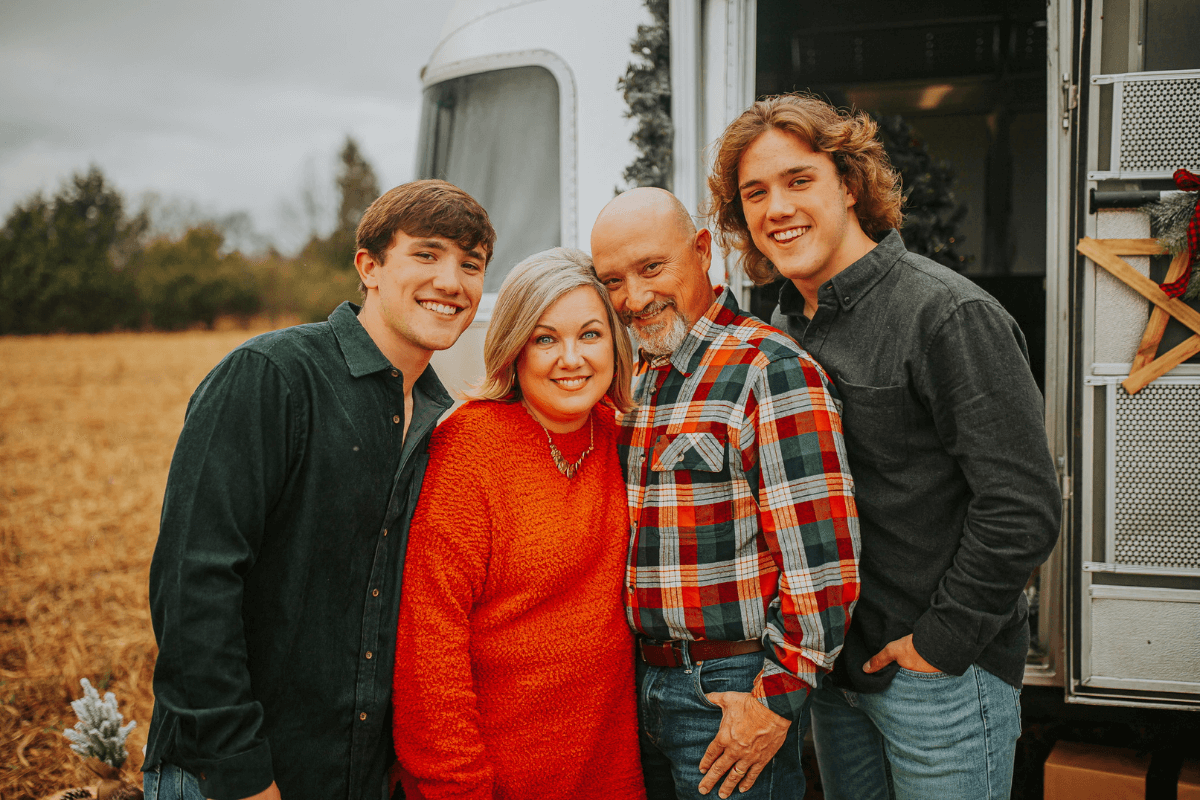

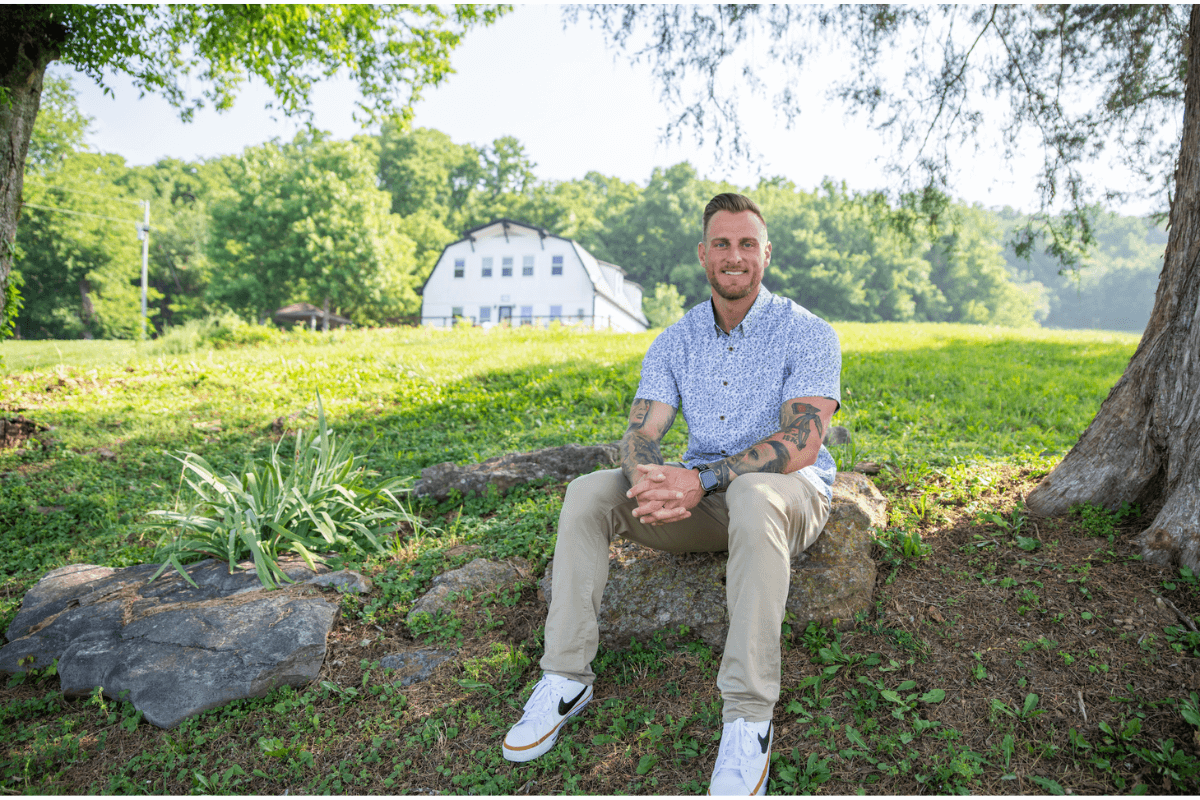

“There were so many moments that God reminded me that He is always faithful, and my family was always a constant encouragement,” Valleroy said. “While in pharmacy school, one of my friends introduced me to my husband, Noah. We got married in September of last year. He has been one of my biggest supporters. I graduated from Union in May, and we moved back to Middle Tennessee with our cat, Daisy.”

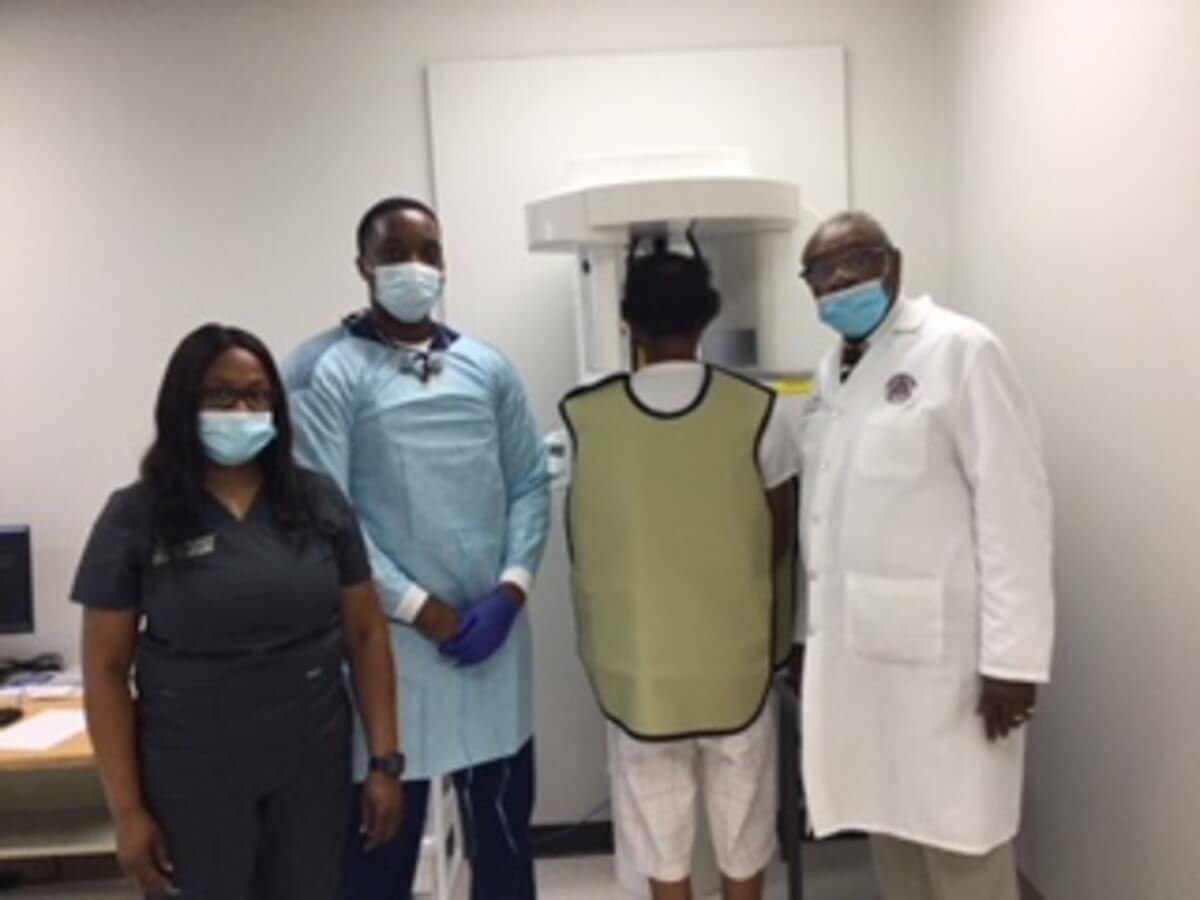

When Valleroy returned to MTPS as an adult, her dreams came full circle. That little girl who had once been afraid to dream hung her diploma above the same counter she used to clean in high school.

“It feels so surreal to be back. The pharmacy carries so many memories. Not only from my time there as a pharmacy assistant, but also from when I spent many afternoons there after school with my mom. It really feels like coming back home.”

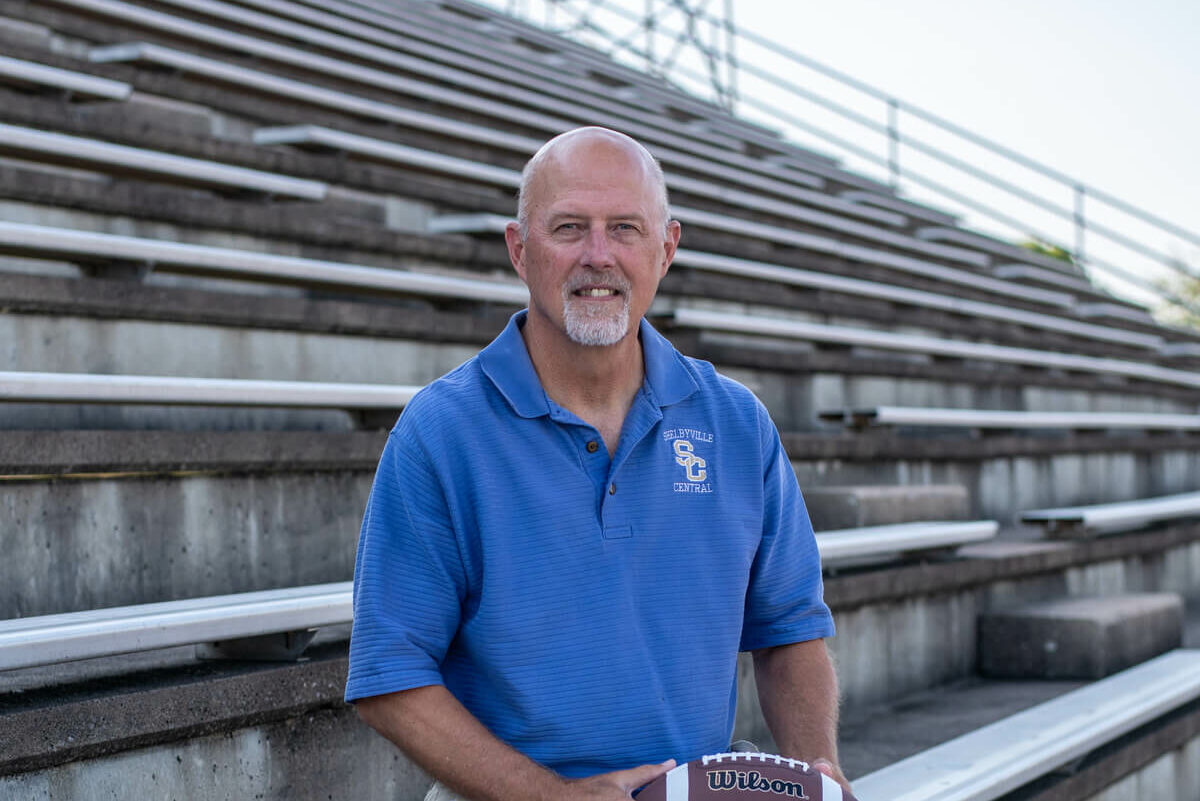

MTPS provides pharmaceutical ser- vices to nursing homes, assisted living facilities, group homes for special needs patients, and hospice facilities. Valleroy said,

“The most rewarding part is knowing I am helping some of the most vulnerable people. Pharmacy school gave me the confidence and knowledge to advocate for my patients. Whether by speaking with the patient’s doctor about proper medication usage or with the patient’s insurance about medication copays, patients need someone to fight in their corner and ensure they are the healthiest they can be.”

Valleroy advocates for patients whose charts cross her desk and for those who work alongside her in pharmaceuticals.

“During my time in pharmacy school, I was able to meet with our state legislators to advocate for law changes to help protect pharmacies and pharmacy employees.”

With every patient she serves, Valleroy shows that the future of health care is in capable, compassionate hands. GN